Am I a big fat hypocrite on speech?

Democrats didn’t get worked up about Biden strong-arming social media platforms. Do they have a right to get angry about Jimmy Kimmel?

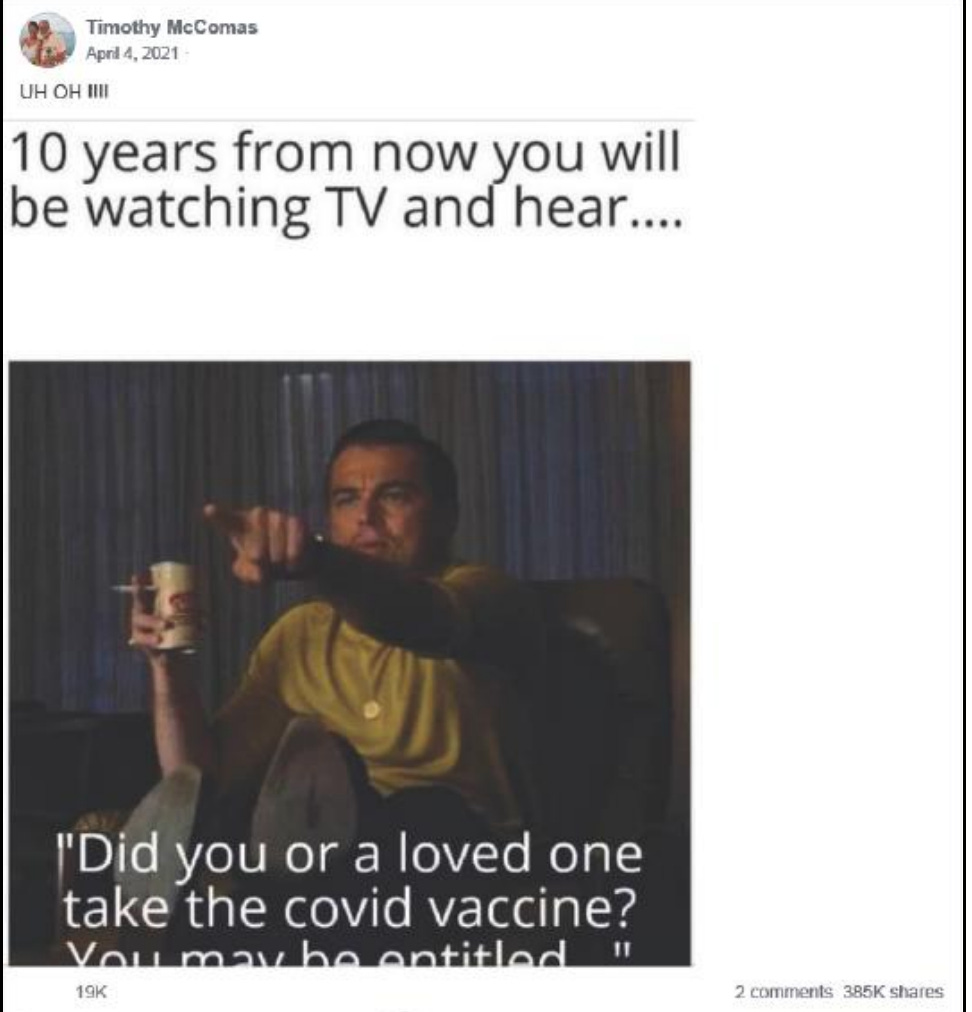

A Leonardo DiCaprio meme, a Tucker Carlson monologue, and an Amazon paperback titled “Anyone Who Tells You Vaccines Are Safe and Effective Is Lying.” All became targets of the Biden administration’s campaign to rid social media and online bookstores of what it saw as deadly misinformation related to COVID-19 in 2021, an effort that involved intense lobbying platforms behind the scenes and in public.

Now, Alphabet, the parent of Google and YouTube, has become the latest tech giant to say that the government’s pressure campaign went too far.

In a letter this week to congressional Republicans, lawyers for the company said that former White House officials pressed it to remove videos that didn’t actually violate any user guidelines. Biden and his team also “created a political atmosphere” aimed at making platforms moderate posts more zealously, Alphabet said.

“It is unacceptable and wrong when any government, including the Biden Administration, attempts to dictate how the Company moderates content,” the letter stated. As a mea culpa, YouTube is now planning to let creators rejoin if they were kicked off the site for violating COVID or election-related content rules the company has since dropped.

Other tech companies have been less careful and legalistic with their criticisms of Biden’s efforts. Last year, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg told Joe Rogan that the administration “tried to censor anyone” who criticized its vaccination efforts and “pushed us super hard to take down things that honestly were true,” like the idea that the shots had side effects.

Many of these concerns are resurfacing in the wake of the Trump administration’s own blatant assault on the First Amendment last week, when the head of the Federal Communications Commission effectively ordered ABC stations to boot late-night host Jimmy Kimmel from the air, or risk losing their broadcast licenses. A number of conservatives have tagged Democrats with hypocrisy for getting outraged over the comic’s suspension, when they stayed silent over Biden’s treatment of social media. False equivalences are the bread and butter of crisis management, but when Avik Roy, a conservative health care wonk I respect, also joined in the chorus, I decided to take a closer look.

Did the Biden folks really cross a line by leaning on social media companies about their content moderation practices?

It’s honestly a close call, but I don’t think so. At times, officials overreached with their requests and got more deeply involved with content decisions than many Americans were comfortable with. But fundamentally, my read is that the administration stayed within reasonable legal and moral boundaries in its attempts to stamp out bad information in the face of a true national public health emergency where lives were very much on the line.

For some reason, we have memory-holed just how deadly and uncertain the pandemic was. At the high point, the week Biden was inaugurated, more than 23,000 people died. Managing communications that have life or death consequences is not the same as going after the broadcast licenses of network affiliates if they don’t silence a late-night comedian for insinuating that Charlie Kirk’s murderer was MAGA-aligned. And it’s important to be capable of making a distinction between them if we’re going to have a healthy conversation about free speech in America that doesn’t devolve into glib absolutism.

The legal perspective

The Supreme Court has long held that the government is not permitted to “coerce a private party to punish or suppress disfavored speech” on its behalf, as Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in last year’s National Rifle Association v. Vullo. Or, to put it another way, the White House can’t force a company like Facebook to take down a post using threats, no matter how noxious. It can only ask, the same way officials occasionally urge journalists to hold news stories for, say, national security reasons.

Exactly where that pressure turns into illegal “coercion” is an inexact matter of judgment, which some federal appeals courts have tried to deal with by administering a complicated four-step test. But lording the possibility of direct retaliation over a company is pretty clearly out of bounds.

In Vullo, Sotomayor wrote that public officials cross the line when their cajoling can be “reasonably understood to convey a threat of adverse government action.” The justices ruled unanimously that New York’s powerful Department of Financial Services potentially violated the NRA’s free speech rights by pressing insurers to cut ties with the gun lobbying group, in part by making it clear companies could face regulatory consequences if they didn’t.

In the seminal 1963 case Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, meanwhile, the court found that a Rhode Island commission stomped all over the First Amendment rights of publishers when it threatened local booksellers with prosecution and police raids unless they took certain titles off their shelves.

Which brings us back to Biden and COVID. The upshot is that while the president’s team was extremely pushy and sometimes foul-mouthed in their dealings with social media companies, they never appear to have gone full mafioso by threatening actual regulatory punishment for companies that didn’t cooperate.

In 2022, a group of Republican-led states and prominent critics of the administration’s pandemic response sued, arguing that Biden’s campaign to make social media companies tighten their moderation policies had censored their speech. A Trump-appointed federal trial court judge in Louisiana, Terry Doughty, initially ruled in their favor, issuing a preliminary injunction barring the administration from meeting with the tech platforms on moderation or even flagging posts.

Last year, however, a 6-3 Supreme Court tossed the suit on standing grounds, finding that the plaintiffs couldn’t show that they personally had ever been silenced due to Biden’s requests, or that they might be in the future. As a result, the justices never resolved the bigger First Amendment questions about whether the administration’s behavior was kosher. But the legal record in the case is instructive.

In his trial court decision granting a preliminary injunction, Doughty listed 22 examples where Biden’s team supposedly tried to “coerce” social media companies into censoring content. Most of it consisted of very intense jawboning. The administration demanded data on how platforms were monitoring COVID content, accused them of “hiding the ball” on moderation, and dropped the occasional f-bomb. They asked to know why a specific Tucker Carlson post hadn’t been squashed, because it had 40,000 shares, and why Twitter hadn’t kicked off reporter Alex Berenson, who was patient zero for a lot of misinformed vax skepticism.

One official warned that the White House was internally “considering our options on what to do about” Facebook’s lack of cooperation. Biden himself turned up the heat when he publicly accused social media companies of “killing people” by failing to limit anti-vaccine material.

But as The Washington Post reporter Philip Bump noted at the time, only one item on the list involved anything even remotely resembling a direct threat of punishment. The judge pointed to comments by White House Director of Communications Kate Bedingfield made during a Morning Joe interview, in which she suggested that Biden might support changes to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act because social media companies had been irresponsible.

Eliminating Section 230, the law that protects social media companies from being sued over issues like libel based on content posted by their users, would, in fact, be a gut-punch to the industry. And Biden was certainly enthusiastic about the idea: While running for president in 2020, he told The New York Times that the legal shield should be revoked and that he had “never been a big Zuckerberg fan.”

But killing the law would have required an act of Congress. Meanwhile, it’s worth looking at what Bedingfield actually said on Morning Joe.

Mika Brzezinski: As a candidate, the president said he was open to getting rid of section 230. And I’m just wondering if he’s open to amending 230 when Facebook and Twitter and other social media outlets spread false misinformation that cause Americans harm, shouldn’t they be held accountable in a real way? Shouldn’t they be liable for publishing that information and then open to lawsuits?

Bedingfield: Well, we’re reviewing that. And certainly they should be held accountable. And I think you’ve heard the president speak very aggressively about this. He understands this is an important piece of the ecosystem. [Note: By “this,” Bedingfield appeared to be talking about the issue of misinformation, not Section 230.]

It is not exactly an earth-shaking development when the president’s aide says, “well, we’re reviewing” his long-held policy position. If anything, it’s a nonanswer. More than a year later, Biden held a roundtable where he called for axing Section 230, but it was framed as something Congress would have to do, not punishment he could personally mete out to companies who refused to go along with his demands on COVID.

The Trump administration, in contrast, had genuinely tried to use Section 230 as a cudgel. Late in his first term, the president issued an executive order that attempted to strip Section 230 protections from social media companies if they were too aggressive on content moderation, which he saw as hurting conservatives. (Biden quickly withdrew it upon taking office).

One complicating factor in all this is that the Supreme Court has made clear that threats to companies “need not be explicit” in order to run afoul of the First Amendment — and there’s no question that Biden’s team leaned hard on Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube in ways they found concerning. Still, it’s worth stopping here to compare Biden’s intimidation tactics to what Brendan Carr, chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, said after Jimmy Kimmel made a somewhat misleading comment about the assassination of Charlie Kirk.

“I mean, look, we can do this the easy way or the hard way,” he told podcaster Benny Johnson. “These companies can find ways to change conduct and take action, frankly, on Kimmel or, you know, there’s going to be additional work for the FCC ahead.” He later elaborated on exactly what behavior he wanted to see:

Again, there’s actions that we can take on licensed broadcasters. And frankly, I think that it’s really sort of past time that a lot of these licensed broadcasters themselves push back on Comcast and Disney and say, “Listen, we are going to preempt. We are not going to run Kimmel anymore until you straighten this out because we, we licensed broadcasters, are running the possibility of fines or license revocations from the FCC if we continue to run content that ends up being a pattern of news distortion.

As Republican Sen. Ted Cruz put it, “that’s right out of ‘Goodfellas.’” Notably, ABC’s network affiliates have followed Carr’s dictate and started preempting Kimmel. And it’s much more the kind of attack on third-party speech the court has previously stepped in to stop.

Free speech is more than just staying on the right side of the law

Even if, like me, you think Biden probably stayed on the right side of Supreme Court precedent, or at most straddled the line, there’s a broader question about whether his actions went overboard. The steelman version of the case, I think, is that even if the social media companies weren’t facing explicit threats from the administration, large companies have to deal with the government all the time, and there is good evidence they felt the need to acquiesce to the administration’s concerns as much as possible for regulatory reasons.

As House Republicans recounted in a report last year, Facebook tightened its content moderation policies in 2021 after Nick Clegg, then Meta’s head of global affairs, sent an email saying the company had, “bigger fish we have to fry” with the administration and should, “think creatively” about how to cooperate.” YouTube’s public policy team sent an internal note saying it would be “hugely beneficial” to have the product team brief the White House because the company needed to work with the administration on “multiple policy fronts.”

This kind of indirect pressure is not a small consideration. After all, Trump didn’t come out and say to ABC affiliate owner Nexstar that he would kill their pending merger if it didn’t take action on Kimmel, but just about everybody thinks that played into the company’s thinking, much to the outrage of Democrats. Or, imagine if the White House began bombarding Facebook with requests to take down every post that called Trump a fascist, having made clear to the world that it will bring down its regulatory hammer on companies that don’t go along with its demands.

The Biden team’s deep, day-to-day involvement in moderating also set off alarm among free speech advocates outside the Republican Party. In an amicus brief supporting plaintiffs, the group FIRE wrote that government officials became “so entangled with social media platform moderation policies that they were able to effectively rewrite the platforms’ policies from the inside.”

Plus, some of the administration’s requests really did seem excessive. At one point, for instance, it pushed Facebook to take down a popular Leonardo DiCaprio pointing-at-the-TV meme, which joked that one day lawyers would be running mesothelioma-style ads for vaccine side effects (Facebook refused). Comedians and memes are obviously an important source of news these days, but also, you have to pick your battles.

Still, you have to balance those considerations with the broader context of 2021, which is that people were dying, and misinformation about vaccines almost certainly played a role. The United States ended up with one of the world’s highest COVID mortality rates, in part because our vaccination rates were so much lower than other countries’. And researchers concluded that Republicans had higher excess death rates than Democrats during the pandemic, even controlling for factors like age, a gap that widened once the vaccines became widely available. Some people’s social media feeds probably did get them killed.

In general, we don’t expect administrations to be completely hands-off on speech when there are lives at stake. If a reporter finds out about an international hostage negotiation, for instance, the State Department might ask them to hold off on publication or to withhold important details to prevent talks from blowing up. I don’t know anybody in the industry who considers that kind of request an unacceptable infringement on the First Amendment.

Similarly, there needs to be some workable standard about when it’s OK for the White House to push social media companies for a bit of responsibility, given their role as America’s most powerful publishers. I think that if some public and private hectoring could save a lot of lives, that reaches what constitutional lawyers call a legitimate government interest.

If we’re weighing lives against the freedom of posters to speculate about vaccine efficacy, one argument in the poster’s favor is that Biden’s approach didn’t obviously work. COVID conspiracies and misinformation still proliferated, and the sense that the administration was trying to hold back information may have fueled cynicism among conservatives.

But my hunch is that letting social media be even more of a free-for-all probably wouldn’t have made the situation better. And it was clearly reasonable to at least try holding back the flow of falsehoods.

Which is to say, trying to save hundreds of thousands of lives is not the same as silencing Jimmy Kimmel.

While I agree what Trump is doing is worse and qualitatively different, I’ve come to the view that what the Biden administration did violated the spirit of the first amendment. While I detest vaccine skeptics, the government shouldn’t pressure private companies to censor them.

Additionally, it generated real backlash from many previously non-partisan or even Democratic-leaning figures, as well as the tech industry itself. This is part of what drove people like Joe Rogan and even Elon Musk to the right. And now it makes Democrat’s criticisms of Trump on speech feel not as credible with these people. So even setting aside the legality and morality, pragmatically it was a disaster.

Based on this kind of cold calculus of whether giving up civil liberties is worth it if you argue it within a legal framework, I’m sure you can rationalize all the worst excesses of the well intentioned War on Terror. Weak article.