An abortion ban pushed me toward abortion

Is this what the pro-life movement intended?

I believe authors should be willing to sign their names to their opinions. Withholding a byline limits readers’ ability to judge a source and can invite justified skepticism. We made an exception here because the author faces credible risks — legal, professional, and personal — if she were to be identified.

In considering whether to publish this piece, The Argument verified her identity and key facts (including medical records, travel documentation, and contemporaneous communications). We have omitted minor details that could expose her, while preserving the substance of her account. Publishing this account is in the public interest. The author shows, concretely, the creeping illiberalism of current abortion laws in Georgia; laws that threaten the individual’s dominion over her body and life. We retained counsel with First Amendment experience to review our process and the piece.

Publishing this required input and expertise from many people inside and outside The Argument. However, the decision to grant anonymity — and any criticism — rests with me.

- Jerusalem Demsas, Editor-in-Chief

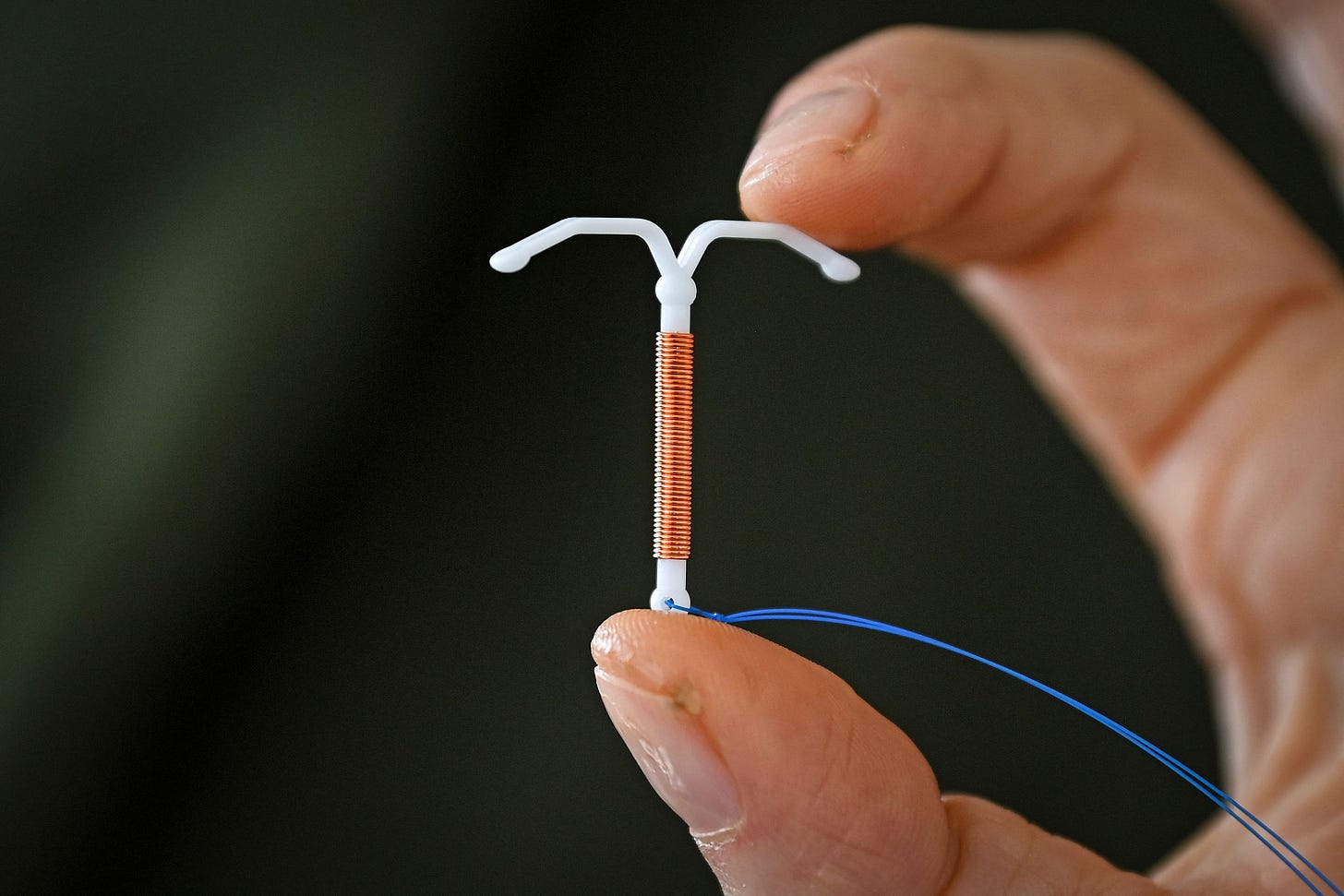

I loved my IUD. I named her “Lady Liberty” because she was made of copper and horny for freedom. So I felt betrayed when I learned that Lady Lib had quit on me — that is, she had just stopped working without bothering to let me know.

The traitor had passive-aggressively moved out of place in my uterus, allowing my husband to knock me up and leaving me in that all-too-precarious position I had never really imagined for myself: carrying an unplanned, high-risk, geriatric pregnancy in post-Roe America.

Cards on the table: I’m a white woman living in a major U.S. city with good health care and a matcha-latte budget. So my story isn’t a particularly harrowing or life-threatening one. Rather, it’s a cautionary story for anyone who takes comfort, the way I used to, in the idea that you can plan, buy, or luck your way to guaranteed safety and freedom.

Even my considerable advantages could not totally insulate me from the fact that when my IUD failed, my health care providers could not help me. They were hamstrung by state law because I failed to realize I was pregnant until it was too late.

Most of my weird symptoms — spotty, irregular periods, fatigue, insomnia, bloating — were mild, and they sounded a lot like the perimenopause symptoms several friends my age had been bitching and bonding over lately.

It was during one of those perimenopause dinner conversations when a friend shared that her youngest child, now in third grade, had resulted from a failed IUD years ago. I dropped my fork and it clinked loudly, like when people receive alarming news in the movies. She might as well have unzipped her skinsuit to reveal that, underneath, she was BigFoot: a creature I was surprised to learn actually existed in real life. I thought about my own IUD and how my breasts were feeling a little tender, and I poured myself another glass of wine.

A few nights later, I was up in the wee hours thinking about bigfoot. I pulled out my phone and ordered a box of home pregnancy tests, just for peace of mind. I took a test as soon as they arrived, a couple days later, and after three positive tests, my mind felt anything but peaceful.

I Googled Georgia’s abortion laws, hoping to prove my recollection wrong. Was the ban really in effect after just six short weeks? It was.

I dialed my GP’s office from the car on my way to pick up my daughter from school. I was put on hold, and the Muzak played through my car speakers as my mind raced over the questions I knew the doctor would ask.

When was my last period? Not totally sure, it had always been irregular and spotty.

What symptoms had I been experiencing? Most of them, come to think of it.

And for how long? For at least a month, maybe two. Or longer. Shit.

My GP could squeeze me in at 7:30 the next morning. Good, I thought. Then we could talk about my options. I hung up the phone, feeling a little relieved for a moment, and I looked up to see my fifth grader bouncing up the sidewalk toward the car, eyes bright, backpack heavy. I smiled and waved that little mom wave, and she smiled back.

I thought about how, when I realized I was pregnant with her, I’d felt so happy. So safe. I thought about how I’d shared the news with my husband by placing a single hot dog bun in our oven and telling him to go look inside it. How I’d remained blissfully unaware of my condition until I was already 12 weeks along.

By 8 a.m. the next morning, I had peed in a cup and my doctor was telling me what I already knew: I was indeed pregnant. Okay, but how pregnant? She asked me the questions I knew she would ask. I gave her my answers.

My doctor explained that, unfortunately, she could not remove my IUD safely at this point because doing so might harm the pregnancy. I explained that I was more concerned with removing the pregnancy than with removing the IUD.

As she came to understand my wishes, her expression and her tone turned from calm to thinly veiled concern, maybe panic. And I realized she couldn’t help me even if she wanted to.

Okay, I thought. Let’s take this one step at a time. The first step was to get an ultrasound so we could see how far my pregnancy had progressed.

My doctor’s office didn’t have an ultrasound machine, so my GP made a few calls for me to local OB-GYNs. She even called a place that does orthopedic imaging, like for sprained ankles or broken arms. But there was no one available and certified to do the kind of ultrasound I needed.

I took the rest of the day off work to figure this out. I was resourceful. I could do this.

Friends texted with numbers and reached out to their friends and their sisters who are doctors and might call in a favor to a colleague. I called just about every OB-GYN within a few hours’ drive, but wait times at OBs have increased precipitously, as many providers have left the state since the Dobbs decision.

So it would be a few weeks before I could get an appointment anywhere.

“A few weeks” might not sound like too long to wait for an ultrasound. But consider that the only way to accurately and legally determine how far some pregnancies have progressed is with an ultrasound. And in states like Georgia, the timeline matters because your rights are tethered to it.

The longer before you get an ultrasound, the longer before you know what rights you still have.

That’s the thing about reproductive health care deserts. The problem is more than mere inconvenience. It’s the systematic and purposeful inhumanity of telling women who are seeking medical care to go fish until it might be too late to actually help them.

After yet another dead-end call, my phone was hot from overuse. I put it down on the kitchen table and looked up at an analog wall clock I never look at. I tracked the second hand, watched it tick away. Like pressing on a bruise just to feel it.

I began to feel urgently and profoundly unsafe.

If I were to stay pregnant, how would my doctors and I safely navigate the slew of serious pregnancy complications that are more likely with a pregnancy like mine (over 40 and with an IUD in place), including infection, sepsis, late-term miscarriage, placental abruption, and preterm delivery? Navigating those risks safely might require abortion care, and doctors can’t do that here.

It was clear to me that staying pregnant might threaten my first priority, which is to be around to mother my 10-year-old daughter. Sure, the chance of life-threatening complications is low, but the chance of getting pregnant with an IUD is just 1%, and that already happened to me. I was in no mood to tempt fate.

My state’s “pro-life” law robbed me not only of the ability to terminate my pregnancy safely and locally, but it also robbed me of the opportunity to “choose life” safely and locally.

It felt unsafe and irresponsible to stay pregnant in Georgia, no matter how I might feel about the pregnancy itself. And who had time for feelings anyway? The clock was ticking.

Feelings about my situation took a back seat to the facts of my situation:

Fact #1: I had been practicing responsible birth control and I got pregnant anyway.

Fact #2: There was no doctor within a few hundred miles who could legally help me get the abortion care I wanted now or that I might need later if I stayed pregnant and something bad were to happen.

Fact #3: I was running out of time.

Fact #4: To get the care I needed to feel safe, I would have to flee.

So I did. Because I was able to. (See aforementioned matcha-latte budget.)

That was when I started calling Planned Parenthood.

I am slightly ashamed to admit that before this moment, I hadn’t known Planned Parenthood was really for people like me. I thought it was for people without adequate health care.

It had never before occurred to me that by dint of where I lived, I was one of the people without adequate health care.

That afternoon, I learned all I could about abortion laws, from the required waiting periods to the operating hours at every Planned Parenthood location in every state that borders mine — and in all the states that border those states.

Could I stay with my cousin in North Carolina, where there was a 72-hour mandatory waiting period between “state-directed counseling” and abortion care, only to possibly learn too late that I had passed the state’s 12-week cutoff?

Or should I drive up to Virginia and spring for a hotel room a full week later in order to make the first available appointment for same-day care?

It felt less like scheduling a doctor’s appointment and more like planning a heist; mapping out clues in a cold case with so many thumbtacks and red strings.

Finally, I landed on a solid lead.

I took off work and got on a plane later that day, flying halfway across the country to a state with saner laws.

They had drug-sniffing dogs at airport security. I wondered: Could the dogs sense that I was pregnant? I felt a little like I was smuggling something illicit.

After all, some would consider me a criminal. In Texas, my husband might be held liable for aiding and abetting me by buying me a last-minute plane ticket while I packed a suitcase. And earlier this year, my own state legislature introduced a bill criminalizing abortion.

To pass the time at airports, my daughter and I sometimes play a people-watching game where we make up stories about our fellow travelers. Where were they going? Why? Now I wondered if anyone at my airport gate could guess my story. Neither business nor pleasure, thanks. I’m a reproductive refugee in my own country.

A family member met me at the airport and drove me four hours to a Planned Parenthood location where I had made an appointment for the next day. They would do the ultrasound and provide same-day care.

I arrived at the clinic the next morning, sleepless and uncharacteristically early. A sweet older gentleman in a brightly colored vest reading “Escort” smiled and showed me into the building. For the first time in a few days, I exhaled.

The care I received was excellent.

I had an ultrasound and received education and counseling, as well as all the time I needed to think about my decision. Then, to prepare for my abortion procedure, they gave me some medication that would soften my cervix while I sat in the waiting room for about two hours.

People came in and out of the clinic, and to pass the time, I played my airport people-watching game, or a version of it. I asked not where they were going and why, but how they were feeling.

A young woman nuzzling her boyfriend. In love.

A man a bit younger than me, sitting alone, flipping through a pamphlet. Nervous.

An older woman holding a younger woman’s hand. Safe.

My mind drifted away from the people in the room and to the people outside it, in my home state and across the country. I’m no demographer, but I figured for every one of the people in this room, there might be dozens who would give anything to be here. And I started to cry.

A middle-aged woman sitting alone, weeping silently about what her country has come to. Furious.

The total cost of my abortion, including travel and medical fees, came to about $3,000 out of pocket. And it would have cost more if my people hadn’t shown up for me and given me a free ride and a place to stay. Not to mention the fact that I could quickly take time off work without worrying about losing my job.

But most Americans live paycheck to paycheck and many can’t afford an emergency expense of this magnitude. It’s a grotesque kind of privilege that feels embarrassing to possess, really — like a third home in Aspen or a Birkin bag.

I know I made the right decision for me, body and soul. But still, I mourn.

I mourn an alternate reality without extreme abortion laws, one in which I felt safe enough to seriously consider staying pregnant and navigating the risks together with my doctors. And I mourn for the many women and girls in this reality who are navigating this system without my good fortune. Finally, I mourn the future I thought we were building for our daughters in this century, even as I steel myself to fight for the dregs of the progress our mothers made in the last one.

On the four-hour drive back from the clinic, I looked out the window a lot, the way I used to do when I was a kid in the back seat: riding past these same fields and farms and small industrial towns, drawing hearts and smiley faces on the fogged-up window.

Outside, middle America whooshed by me. The high corn was reaching, the wheat was leaning, the wind turbines were turning, and it seemed the whole world had started to move. For days, the world had felt stuck, paralyzed like a sailboat with no wind. Now, the sails were filling up, and it felt like I was back at the helm.

But I know better than that. Now I know that any semblance of control I might feel is an illusion.

Back in the waiting room at Planned Parenthood, I had overheard the nervous, pamphlet-reading man ask the receptionist, “You’re gonna give me Valium or something, right?” I suspect he was there to get a vasectomy, because Planned Parenthood does those, too. (My husband will soon join that quickly growing club.)

But because vasectomies can sometimes fail, I’ll get a new IUD. A backup, not a guarantee. It’s all I can do to feel just a little bit safe. A little bit free.

This is the most expensive story we have ever published. Between legal review and fact-checking, it demanded extraordinary time and care. Here’s part of the email that convinced me it was worth it:

…if our policies weren’t so illiberal, I very well might have decided to stay pregnant. We have plenty of money, support, and love to give. We even have a spare bedroom that would make a great nursery. But given my risk factors, staying pregnant in Georgia today felt way too unsafe. And there is no freedom without safety.

The expense was high for a small, independent media company but I did not hesitate to pay it and I do not hesitate to leave this story free to the public. The Argument was created to defend our most basic freedoms. We hope you will join us in that mission.

A moving and important piece; thank you for publishing it.

Tremendous article. Hope it finds a wide audience, and hope we receive more humanizing stories like this from all those impacted by the right's Draconian anti-abortion laws. Too many unheard tragedies that remind us, time and again, that politics and policies are matters of life and death.