Creative destruction is a miracle. It’s also a political problem.

The Nobel Prize in Economics has a lesson for abundance liberals

For those of you who were off for Indigenous Peoples’ Day/Columbus Day, welcome back! If you spent more time than you’d like scrolling through social media, you might like this piece we ran yesterday about Jerusalem’s quest to overcome her severe short-form video addiction. We also released a new episode of our podcast about Tylenol, RFK Jr., and the autism panic with columnist Dr. Rachael Bedard.

No matter how much the world changed for most of human history, the realities of gut-wrenching poverty and subsistence farming remained the same. An average grandfather talking to his granddaughter could picture her life as easily as I could picture my childhood home. He could reasonably expect she would grow up quite similar to him, surrounded by the same tools, eating the same things, life on the edge of survival.

I am perhaps not the average case, but my father’s father, who died before I was born, was himself born in Digsa, Eritrea, a rural village where I have never set foot. I don’t think he could have imagined my life, typing at my personal computer in an air-conditioned building, drinking filtered water from the tap and ordering all my conveniences on Amazon. My own father, who was born in Eritrea’s capital city, Asmara, learned to code by punching holes in cards and lining up with his stack at a mainframe, hoping he hadn’t made a mistake.

What do I expect for my future children? I have absolutely no idea, maybe they will be canceling me for disapproving of their robot boyfriends as they vibe code and mainline Ozempic for sleep.1

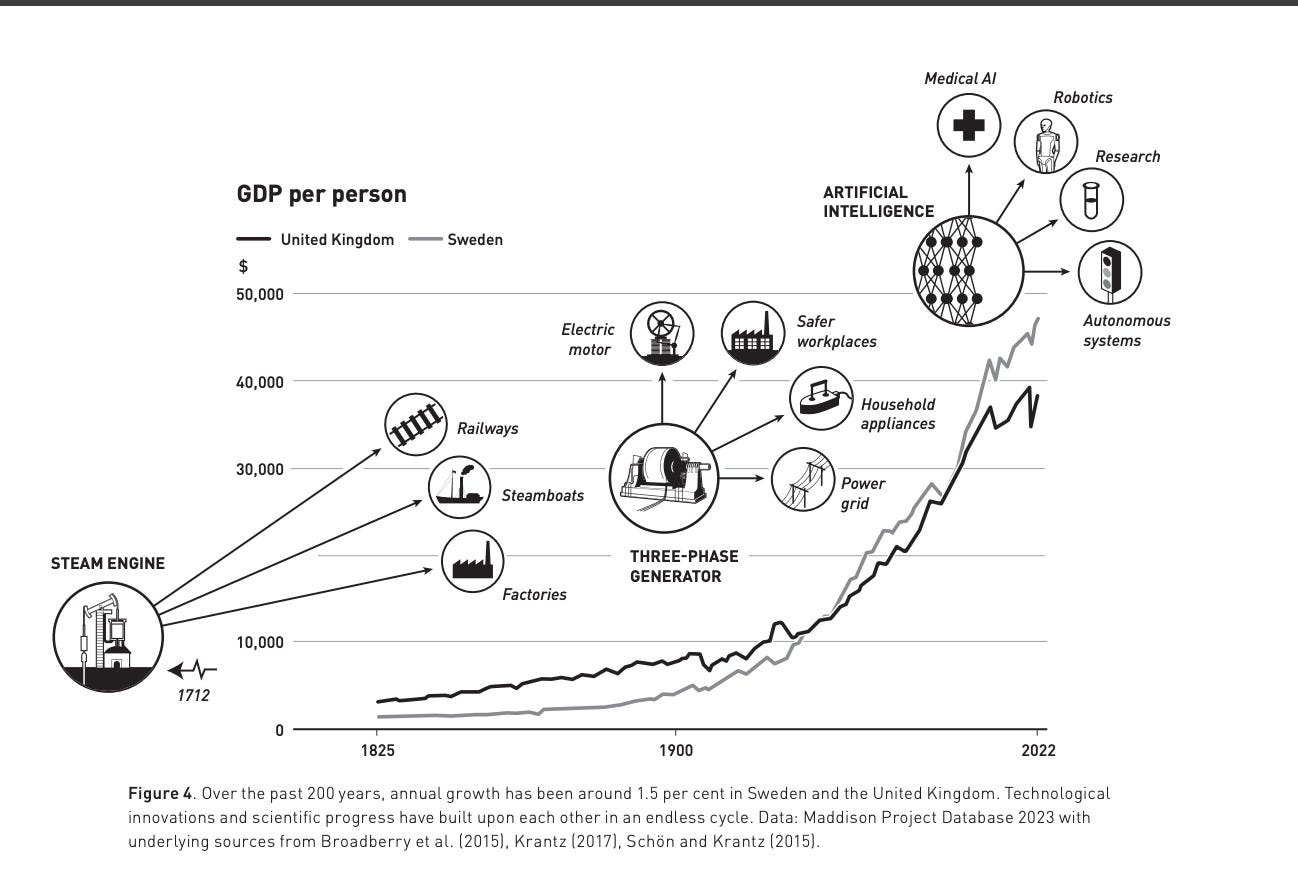

Over the past 200 years, economic growth has become both fast and normal, so much so that many of us take it for granted. This is perhaps the most important graph in human history:

There’s a tendency in some circles to roll one’s eyes at “line go up!” graphs like this one. What is “gross domestic product” anyway? GDP measures the value of all the final goods and services in an economy; on its own terms it means that we are producing more things that we value (things that we consume), like phones, cars, houses, planes, medicine, books, plays, art, clothing … everything.

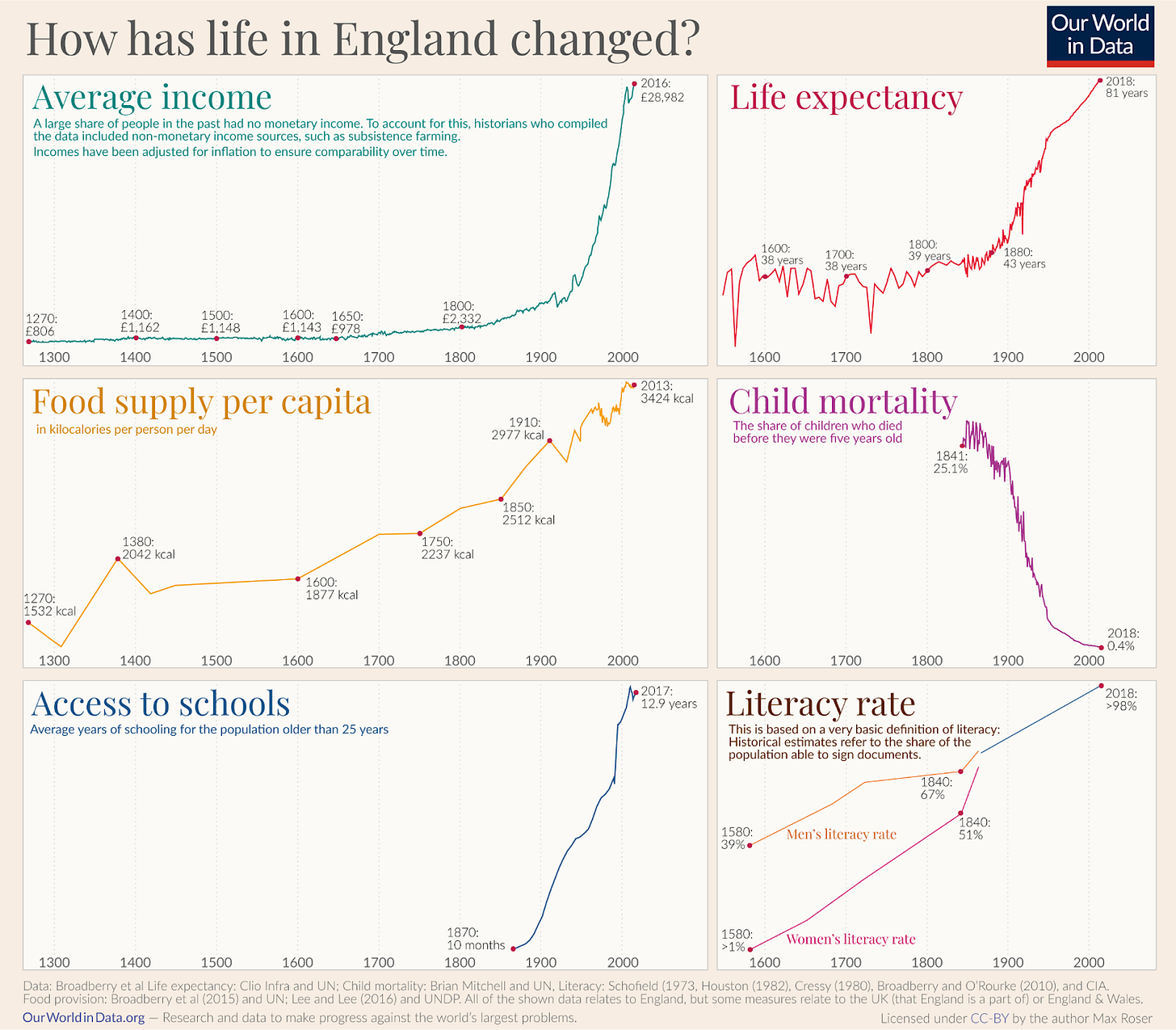

And, unsurprisingly, as this most-important line has gone up, others followed suit. Life expectancy, food supply per capita, child mortality, literacy, and access to schools have all improved as incomes and GDP have risen. This is the development miracle that defines our time.

Yesterday, the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to three economists “for having explained innovation-driven economic growth”: Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt shared the prize. Mokyr was recognized for his work explaining how innovation became a self-reinforcing process that spurred the Industrial Revolution to create our modern world. The latter two won the prize for their model of creative destruction wherein new companies create new products, outpacing the current technological leaders.

Mokyr’s work in particular centered on the importance of ideas and culture alongside technological breakthroughs. In his book A Culture of Growth, he wrote that “The liberal ideas of religious tolerance, free entry into the market for ideas, and belief in the transnational character of the intellectual community were essential to Enlightenment thought.”

Creating a culture tolerant of disruption is just as important as having the new discoveries and engineering marvels themselves. If you’re going to be persecuted for pointing out that the earth revolves around the sun, well, you’re not going to get a lot of scientific progress. Less dramatically, as Mokyr pointed out, the Calico Act of 1700 was pushed by domestic wool and silk producers in Britain to block Indian cotton clothing and was only repealed in 1774.

As The Nobel committee wrote:

“In different ways, the laureates show how creative destruction creates conflicts that must be managed in a constructive manner. Otherwise, innovation will be blocked by established companies and interest groups that risk being put at a disadvantage.”

“Line goes up” does not mean everyone’s life gets better. It means everyone’s life on average gets better. Averages can conceal a lot of pain. There are always losers, and society has to innovate new and better ways of making sure “losing” still means a bare standard of living. But you can’t eliminate the pain of losing altogether. Not if you want society to keep flourishing.

Straightforwardly, the losers of growth, from the elderly homeowner upset that a bunch of college kids are now living in his neighborhood and making a bunch of noise to the small business owner who gets outcompeted by Target to the coal worker who is watching his industry collapse, need to know that losing doesn’t mean the end. These are people with a range of legitimate concerns who need reassurance and material support, but this is also a matter of political expediency. If we — and now I am talking about the pro-growth, positive-sum abundance movement — are going to win over more converts, we can’t ignore the destructive part of creative destruction.

For the winners of the change lottery — the upwardly mobile working class, the lucky immigrants from politically and economically devastated countries, people who moved from areas with no or little economic opportunity to places brimming with hope — it’s not always immediately obvious how costly other people find change. Part of why immigrants in this nation are so dynamic and patriotic is because they are a highly selected group of people that have won the change lottery.

But for a lot of other people, change is either neutral (because they were coming from a pretty high baseline) or negative (because they lost the lottery). I only really came to understand this through my reporting on housing.

When my labor economics professor first assigned a paper connecting measures like zoning regulations that restricted the supply of new housing to America’s rising rents and declining moving rates, my totalizing model was that NIMBYs were simply racists who had to be razed over. I devoured the Moving to Opportunity literature, which showed that when low-income families were provided assistance so they could move to low-poverty areas, young children’s life outcomes skyrocketed. It became my mission to draw more attention to exclusionary zoning laws and the harm they were doing to millions of people as well as the productive capacity of the United States.

But over the years, as I’ve talked with countless people about their opposition to new housing, I’ve found that while bigoted attitudes (particularly toward the poor) could help explain NIMBYism, these attitudes were actually a subset of a broader fear of change. Some of it was demographic change, yes, but lots of it was a generalized fear that new buildings, new people, and new businesses carried with them the threat of upheaval. Somewhere along the way, I realized they were right.

When a large new housing development is built, it does change how your community feels. The skyline can change, the types of people you see can change. What was once familiar has now shifted in ways you can’t fully anticipate. And a lot of people like the way they live now.

But there’s a fundamental misunderstanding undergirding this fear. People who oppose growth assume that if they block new development, they can preserve their cities in amber. The choice, they think, is between change and stability. They are sadly mistaken. The only choice you have — if you’re lucky — is whether you plan for change or have it forced upon you in ways you didn’t expect.

I grew up in Montgomery County, Maryland, a wealthy, progressive county right outside Washington, D.C. In July 2019, the county put a moratorium on new housing in areas where schools had gotten too crowded. The thinking was that schools couldn’t handle any new students, so if we stopped new housing, then we could simply keep things steady.

Enterprising readers will probably know where this is going — Montgomery County reversed the policy after it realized that not only had this policy put serious pressure on housing affordability, but it hadn’t even stopped school enrollment from increasing. Instead, older homeowners were increasingly selling their homes to young, relatively wealthy families.

Change happens whether you want it or not. It’s true at the micro level of your neighborhood and the macro level of the nation. A country can try to freeze its demographics by limiting immigration, but it will become older and less dynamic. It can try to preserve its industries with tariffs, but it will wake up one day to find it has kneecapped its own innovative capacity as its consumers chafe at being unable to purchase the cutting-edge technology other nations take for granted. Stasis is not an option.

There are lots of different kinds of change. Aghion and Howitt describe a form of change that Americans are relatively comfortable with: Sometimes a new product or way of doing business comes out and outcompetes the old winners. Even if that new business really does create a lot of societal value — for instance, Uber or Lyft — society should still take the downsides seriously. Taxi drivers who saw the value of their medallions disappear faced serious personal and economic consequences.

Even when the economy appears relatively stable, that hides a ton of churn. Just look at this graph of layoffs and discharges:

Ignoring the massive spike during COVID-19, we average almost 2 million people losing their jobs monthly even when the economy is doing fine.

The biggest mistake people who agree with me about the importance of economic growth can make is to delay engaging with the distributional consequences. Many people will, no matter how well things are going, be caught in the economy’s natural tumult.

This brings me to Abundance. Of all the critiques of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s recent book, I think the one I find most to agree with in is from People’s Policy Project President — and The Argument columnist — Matt Bruenig:

“I think it would be a huge mistake, on the merits, to sideline whatever focus there is on welfare state expansion and economic egalitarianism in favor of a focus on administrative burdens in construction, both because parceling out the present matters but also because these institutions will determine how the authors’ utopian future will be parceled out,” he wrote.

Bruenig took issue with Abundance’s argument that American liberalism has focused too much on “how near it could come to the social welfare system of Denmark” and not enough on becoming “a liberalism that builds.” The authors also remark that “the world we want requires more than redistribution … we aspire to more than parceling out the present.”

Now, I want to preface this by saying that Klein and Thompson — disclosure, both are friends of mine, Thompson is also a columnist at The Argument and Klein has been of great help as I began this project — are clearly proponents of expanding the welfare state. On health care, the child tax credit, and various other important policy areas, both have been vocal and consistent proponents of redistribution.

But despite all that, they very much did write down in a book that they view the project of Abundance to be — at least in part — shifting focus away from redistribution and toward economic growth. At its core, Abundance is a framework that refuses to accept scarcity as a fact of life. But perhaps confusingly, it is also a framework that demands policymakers be hypervigilant about cause prioritization and trade-offs. There are things — like time — that none of us can make more of (again, until someone invents Ozempic for sleep).

But while I strongly believe that American liberalism needs to focus more on economic growth and innovation, I don’t believe that comes at the expense of redistribution. The whole point of expanding housing, energy, and transportation, the whole point of increasing innovation and productivity, is to make people’s lives better.

Abundance makes redistribution effective. We can and should max out rental vouchers right now. But if you do so while affordable housing is scarce and concentrated in low-opportunity neighborhoods, you risk spiking rent for low-income people and entrenching existing segregation.

The impact of expanding the welfare state is blunted by class-based zoning laws that restrict people from moving near good jobs and good schools and away from long commutes and bad air quality. It is also blunted by our nation’s inability to build public transportation that actually helps people get where they need to go on time.

Growth and redistribution cannot be a two-step process. As our Nobel Prize laureates know well, once the pie has grown, dividing it up means taking it from those who believe they have a claim to it.

You have to redistribute as you grow. You have to make sure that people have a stake in the growth of their community, so that when they notice the irritations of construction on their commute or bristle at different languages being spoken at the coffee shop they frequent, they see that as part of an economic project that sustains their lives.

I don’t think this is easy, and anti-growth and pro-growth moods are at best cyclical (at worst, anti-growthers drag us into economic and political stagnation). But I do think it’s conceptually, morally, and politically better to think of growth and innovation as part of a broader project of human flourishing that necessarily includes the distributional concerns of those who do not have a stake in OpenAI or Google.

They have become a punchline, but the Luddites did very much get crushed under the wheel of progress. We should be prepared: The changes that rocked the world during and after the Industrial Revolution may be dwarfed by the world-changing innovations that may be coming in the next century. If we want to revitalize our culture of growth, we’ll have to do more than point to some averages.

I am begging someone to invent this. I want something that makes it so I never have to sleep again but feel fully replenished at all times. You can do it, scientists, get to work.

Something missing from this account is the importance of regulation in response to disruption. I acknowledge we have to be careful about this. Regulation has to make progress better for people rather than block it. But nonetheless, robust regulation seems important to me.

Take the Industrial Revolution. It destroyed the livelihoods of many craftspeople. These livelihoods were very empowering: they involved working out of the home running an independent business, using a complex skill the craftsperson had mastered.

What replaced these jobs? Long hours doing grueling, repetitive, dangerous work in factories serving the whims of authoritarian bosses. No wonder there was a backlash, even if GDP may have been higher.

We shouldn’t have stopped the industrial revolution from happening, but maybe we could have implemented the kinds of labor norms and regulations we take for granted today back then. Things like overtime pay, minimum wages, OSHA, sick and parental leave (still an ongoing fight!), the two day weekend, mandatory lunch breaks, and bans on child labor.

I’m not exactly sure what the equivalent of these regulations are in the case of housing or AI disruption, but we shouldn’t be closed to regulation in general as a solution. We just have to weigh trade offs.

I think this is part of the story, but it underplays the extent to which people may also be objecting to the real and quite unnecessary costs of the growth that happened in the post WWII era, costs that go beyond just displacement. In the urbanism realm, for example, development, and liberal-establishment-driven urban progress policy generally, during that era very often made cities uglier, less safe, and less family friendly. It didn't have to. And now, we who are pro-development for the usual abundance reasons have a politically understandable burden of convincing people that *our* version will not be like that. That's a burden we can meet, but the work of meeting it can't be neglected if we want abundance to be politically sustainable.