How our surveys work

A deep dive into our polling operation

How do your polls work?

It’s the most common question any pollster gets, and the response is more complicated than you might think. Two different decisions taken by two reasonable people can lead to wildly different outcomes, and the resulting fights over methodology can dwarf an entire Tolkien novel in lore and length alike. Some of these questions include:

How do you determine and recruit the sample?

What do you do if the responses are heavily skewed toward a certain demographic, like when Democrats answered surveys at a much higher rate than Republicans did in 2020?

How do you weight the sample to reflect the population you’re measuring?

There are many answers to these questions, and it’s hard to tell who’s right and who’s wrong. But a good pollster must be transparent about what they actually do and what assumptions they make. So here are ours:

(Warning: this section is extremely detailed. I’ve tried to make this as simple as possible to understand without blasting through the length limits, but there’s a reason this isn’t even going out as a newsletter item.)

The first step in polling is … actually designing the poll.

This is harder than you might think. People process questions in a variety of ways, and the slightest tweak in wording choices can lead to radically different poll results. Bias can creep into questions in a number of ways, especially if you’re not vigilant.

We design our polls with the input of a review board of public opinion experts. These experts have spent a long time in the industry and are some of the most skilled practitioners in their field. They span the spectrum from Republican to Democratic and conservative to liberal, and this helps us best ensure that our surveys aren’t slanted in any one direction.

The polls we design are meant to be short and take no more than six minutes for the median respondent to complete. This detail is really important, because the longer the survey gets, the harder it is to actually represent disengaged voters who drop off midsurvey.

After creating the survey, it’s time for us to contact voters. Our surveys are hosted online. While we design and weight surveys ourselves, we use Verasight to field and collect the poll responses. (This is very much like the partnership between The New York Times and Siena College, where the Times designs and weights the survey while Siena fields.)

Our survey is multimodal, which means we collect data via a host of different contact mechanisms. Respondents are contacted by Verasight in one of three ways: random person-to-person texting, dynamic online targeting, and random address-based sampling. To guard against bots taking the surveys, respondents are verified via multifactor authentication methods including SMS verification and CAPTCHAs. All responses are from validated registered voters.

To ensure responses are sincere, Verasight also removes people who “straight line” or speed through a survey — so if someone just randomly clicks through the questions or completes it in less than 30% of the median completion time, their response is not counted. It’s hard to believe that someone is really engaging with the questions if they are completing a six-minute survey in one minute.

Once Verasight collects the data, it’s time for us at The Argument to clean it and weight it to proportions reflective of the electorate. We weight our sample to be reflective of the electorate by age, gender, education, geographic region, race by education, race by gender, age by gender, and 2024 vote choice. Beginning with our September 2025 survey, we also weight race, age, and gender by Catalist’s modeled Vote Choice Index (partisanship) metric.

The reason for this is simple: To properly represent the population, your sample needs to have the same proportions as the electorate does across a variety of different subgroups. Because our focus is understanding how voters across the nation feel about issues rather than the horse race, we weight our sample to reflect the population of all registered voters in America, rather than people who are likely to actually vote.

Why is weighting important? Well, let’s say you’re measuring presidential vote choice. Women are more likely to vote Democratic than men are, and so if your sample is 59% female and 41% male, you may risk your sample being way too Democratic as a result. Adjusting your sample via weighting to be in line with what the national ratio actually is (54% female and 46% male in 2024) can help avoid this problem and, more importantly, will fairly represent the population you want to actually measure.

You don’t want weights that are too large, of course, because no single respondent should get too much weight, and doing this tends to inflate a couple outliers from hard-to-reach demographics. For example, think about the USC/Daybreak tracking poll from 2016, which massively and artificially inflated Donald Trump’s Black support thanks to one participant who was occasionally weighted 30 times more than the average respondent, and 300 times more than the lowest-weighted respondent.

We generally trim our weights to avoid this problem — for instance, in our first survey, the average weight for a respondent was 1.0, the maximum weight any respondent received was 2.0, and the minimum was 0.4.

A good general way to check the influence that weights have on surveys is by looking at something called the design effect. In simple terms, this tells you how much the weights influenced the survey and how much statistical precision was lost as a result of weighting. The higher the design effect, the greater the impact of the weights.

Unless you’re purposefully oversampling (in which you intentionally sample more of a specific demographic to get a good read on them), good surveys generally tend to try to keep the design effect as low as possible while still representing the electorate properly. As a rough rule of thumb, lots of the survey practitioners I know try to stay under 2.0. In our first survey, ours was 1.2 — for reference, that’s lower than The New York Times’ April 2025 survey (1.36).

One thing I haven’t gone through yet is how we clean and process data. In order to weight the sample, we have to be able to classify each respondent into demographic groups. For this, we draw on a combination of self-reported data, whether from our own questionnaire or Verasight’s profiling questionnaire, and augment it with voter file data. Concretely, here’s how we do it:

Gender and race data are obtained via self reporting on the survey. In the event that users selected multiple races or entered text values for race (we once had someone say “Human” for their race!), we take their self-reported race from their Verasight panel profile.

Region, age, education, and 2024 vote choice were taken from Verasight's respondent profile.

Any null values are imputed using the Catalist voter file.

The portion of people who actually voted in 2024 was weighted to the real election results. The portion of nonvoters was kept fixed from the raw sample.

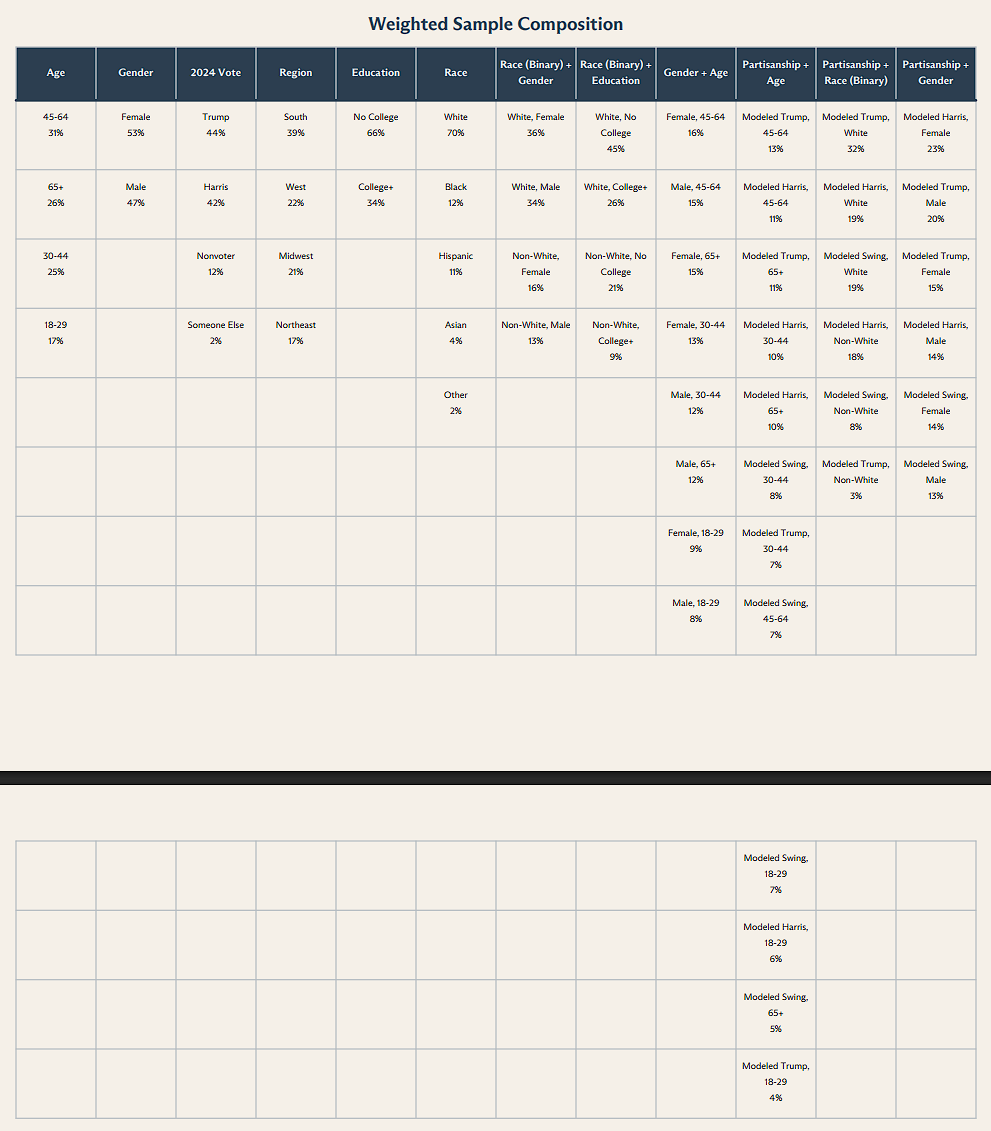

The demographic “targets” for weighting (or, in other words, the demographic composition of the electorate) were derived by measuring the demographic composition of a large sample from the Catalist voter file. For those curious, here is an example of our modeled electorate from our November survey, which had a sample size of 1,562 registered voters.

Now you know the full breakdown of how our polls are conducted. While no poll is perfect, our hope is that our methodological transparency will build trust in how we do our work. Remember that subscribers get full access to our crosstabs, and founding members can suggest topics for us to test — sign up to subscribe or to be a founding member.

Update: Since publishing this article, we have made two changes. The first is that in the process of designing our surveys, we decided to weight by Catalist’s modeled presidential vote choice instead of Vote Choice Index, and we do so across age, race, and gender. This ensures that our crosstabs and subgroups have the “right” number of Republicans and Democrats — e.g., the right number of non-white Republicans, the right number of non-white Democrats, etc.

The reason we picked Catalist’s modeled presidential vote choice variable is simple: its data is newer than Vote Choice Index’s, and the results better align with the exit polls from 2024. This decision was made prior to September 2025 and is reflected on the methodology statement for each survey.

The second change is that as of November 2025, we are no longer weighting our surveys by voter file-modeled income. This is because the modeled income on the voter file overweights the middle brackets ($50K-$100K) while underweighting the rest.

Interestingly, however, the results of this change are barely noticeable — in fact, none of our results experienced a change outside the margin of error, and the average change for any choice was less than 1%. This is because we control for a host of other variables, such as partisanship by demographic, age, education, gender, region, race, and the other variables listed above. After controlling for these, the impact of the modeled electorate’s income shift is minimal.