What happens to college towns after peak 18-year-old?

As the supply of young people dries up, towns built around America’s higher education system will learn what happens when the students stop coming

Earlier this year, on a visit back to my alma mater, Western Kentucky University, I spoke to a student majoring in business who told me he might drop out of college to take a factory job near home. Tuition was going up (again) and he wasn’t sure if there was anything waiting for him at the end of this yellow brick road. He was scared.

I certainly didn’t know what to tell him. I wanted to say the degree would pay off, that education is worth the investment. But I graduated in 2019, months before the pandemic. College has changed, and so have jobs. I didn’t have an answer for him because the institutions themselves don’t seem to have an answer either.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. A student leaving college for factory work — the very jobs that disappeared in the First Rust Belt, now somehow seeming more reliable than a degree. It’s the kind of reversal that makes you wonder if the life path forward is actually backward, or if there’s a path at all. The answer, it turns out, is bigger than one student’s choice.

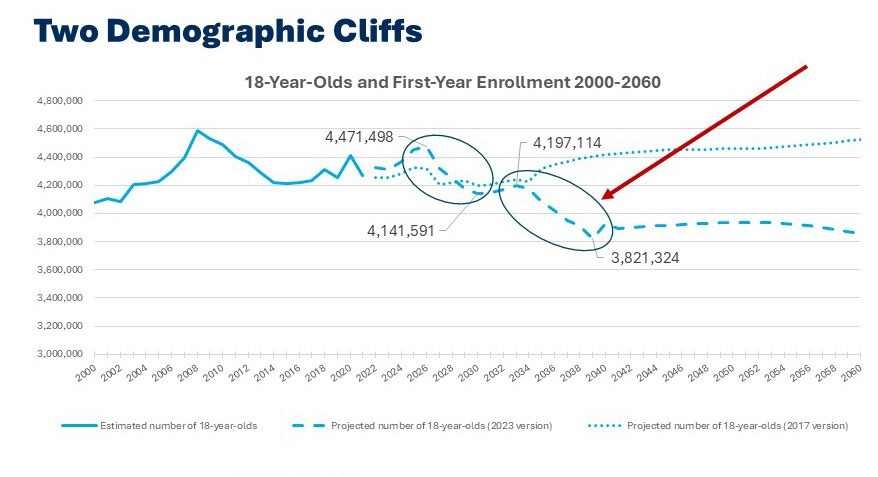

This student, like many others, isn’t just responding to an immediate economic calculation. He’s also caught in an invisible (and increasingly visible) demographic force: America is running out of people his age. Even if colleges fixed their cost and value proposition tomorrow — even if tuition dropped and job prospects improved — there would still be fewer students like him to fill seats. We are hitting peak 18-year-old, and the decline is just beginning.1

Western Kentucky University, like many colleges across the United States, is hollowing out. This isn’t necessarily because they are bad schools — many, like WKU, are great schools. That’s why my alma mater feels like an early warning siren for a much scarier problem.

America is facing its next Rust Belt moment — but it’s not our steel mills shutting down, it’s our education mills. The First Rust Belt was shaped by deindustrialization, globalization, and a changing demand for natural resources. The Second Rust Belt is shaped by falling birth rates, eroded institutional trust, and an aging population. But the local impact could be the same: entire regions hollowed out, communities that feel abandoned, and another generation left behind by the very institutions that promised them a future.

What steel was to the 20th century, education has been to the 21st — an economic engine now running out of fuel. The question is whether we’ll manage this contraction thoughtfully with public investment or watch it collapse chaotically, creating new ghost towns in its wake.

But is the student I spoke to making the right choice — or a rational one? To answer that, we have to understand how we got here — and how we can get out.

The Scope of Collapse

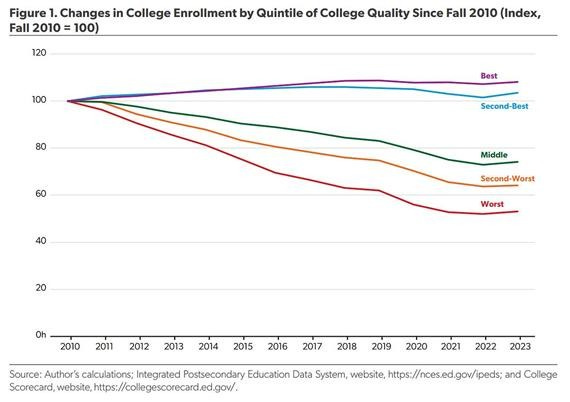

The numbers tell the real story. Undergraduate enrollment across all institutions dropped 12% between 2010 and 2023, falling from 18.1 million to 15.8 million students. Nearly one-third of that drop happened during the pandemic, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. But the slide started long before COVID-19.

Two-year colleges have been devastated, falling 39% from 7.7 million students in 2010 to 4.7 million in 2023. Four-year colleges, by contrast, actually ticked up 6% overall during the same period, from 10.4 million to 11.1 million.

But those aggregate numbers hide regional carnage. The Northeast, as Kevin Carey reported for Vox in 2022, is already experiencing an “enrollment bust” because families are simply moving away. The problem is particularly acute in states like Pennsylvania, which he called the “canary in the demographic coal mine.”

Western Kentucky University is an example of how uneven these numbers can get. WKU was the only Kentucky public university with a fall 2024 enrollment decline, down almost 3% year-over-year, and about 23% below its 2012 peak, according to the College Heights Herald. The administration has shifted from chasing headcount to optimizing net tuition revenue, ramped aid to target “hardworking families,” and focused heavily on retention.

But here’s the most telling data point from the school’s National Student Clearinghouse data: Over 60% of WKU-admitted applicants who don’t attend WKY don’t enroll anywhere. Not at a competitor, not at a community college — nowhere. Colleges are still competing with one another, but increasingly, they’re competing with the labor market itself.

There are two main sources for this data, and they count things slightly differently. The National Center for Education Statistics measures official federal data from schools’ annual IPEDS reports — it’s authoritative but slow. The National Student Clearinghouse gets real-time data from registrar files at 97% of colleges and serves as a better short-term gauge.

According to NSC, public four-year undergraduate headcount has been roughly flat over the past decade, from 7.5 million in Spring 2015 to 7.4 million in Spring 2025. But “flat” doesn’t mean stable. It means many schools are treading water while others drown.

The pandemic accelerated some trends and masked others. The share of undergrads at four-year schools pursuing their degree entirely remote jumped from 13% in 2015 to almost 21% in 2022, according to NCES. That’s been a goldmine for schools with popular online programs like Arizona State University and Southern New Hampshire University, but it’s sucked students out of smaller, traditional campuses that once sustained local economies.

So what happens next? No one really knows.

Carleton College economist Nathan Grawe has projected a 15% decline in all college enrollment between 2025 and 2029. The Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) said it expects high school graduates to peak in 2025, then decline steadily across the West, Midwest and Northeast. The South will grow slightly, but not enough to offset the national drop.

The NCES, by contrast, is comparatively upbeat. It predicted that undergraduate enrollment at both two- and four-year schools will increase going forward through 2031, reaching 16.8 million students.

Who’s right? The skeptics have history on their side. Past NCES forecasts have consistently proven overly optimistic, according to RNL Solutions, a consulting firm that tracks enrollment trends.

But there’s another wrinkle: New Census projections based on the 2020 count rather than the 2010 one show not one cliff but two — We will experience a brief plateau around 2030 from a small baby bump in 2010 to 2012, then another falloff through the mid-2030s.

Then, things accelerate.

By 2030, 20.7% of Americans will be 65 or older, while just 20.2% will be under 18, according to S&P Global. That 0.5 percentage point difference might sound like nothing now, but it’s expected to get bigger and bigger.

The birth rate 18 years ago was at replacement level (2.1 births per woman in 2007), but by 2015, that number had dropped to 1.83. Seniors are the fastest-growing share of the population. That means relatively fewer workers, fewer students, and more strain on Medicare and Social Security.

The economic model of the postwar United States was built on population growth. Now, we’re about to learn what happens when the supply of young people contracts while the promises we made to the old remain in place.

Why this is happening

The demographic cliff is real, and it’s colliding with other forces that make the contraction worse — and harder to solve.

1. The demographic inevitability:

People stopped having children during the Great Recession and never really started back up. The causes for the Great Birth Rate Decline are complex and debated, but the economic barriers are undeniable: Child care costs have risen 153% since 2000, in fact raising a child costs more than $300,000 over 18 years. When family formation is financially out of reach for many young adults, the pipeline of future college students simply dries up.

This is no great secret. You can’t scroll too far on Twitter without seeing someone — including the vice president of the United States — bemoan the state of baby making. But most of the economic and political ramifications have yet to crystallize. Just wait for the Discourse™ then.

But this is the root of the issue — even if everything else was fixed with education tomorrow, the problem remains: You can’t enroll students who don’t exist.

2. Trust:

But demography isn’t destiny — or at least, it doesn’t have to be this severe. The enrollment crisis is compounded by a legitimacy crisis. Trust in higher education has eroded across the political spectrum, and the collapse on the right has been catastrophic.

According to a Gallup poll, in 2015, 56% of Republicans said they had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in colleges; today, only 20% do. Confidence among Democrats and independents has fallen too, by 12 and 13 points respectively.

College is no longer a shared cultural good. For a growing segment of the country, it has become a suspicious institution. Whether these perceptions are fair is almost beside the point; they shape behavior.

Parents who don’t trust colleges won’t push their kids to attend. Students who see universities as ideological echo chambers won’t apply. Politicians who view higher education with hostility won’t fund it.

Why the collapse in trust? The reasons are varied, with the main one being the cost-versus-value concerns as the college wage premium narrows for some degrees. Cultural and political battles on campus have also made universities lightning rods in the culture war. And the perceived meritocracy paradox makes the system feel rigged.

Student loan debt is terrifying. Job prospects are uncertain. AI is already disrupting both how we educate students and what jobs wait for them on the other side.

But there’s another force at work: Real opportunities outside the traditional four-year path are proving that college isn’t the be-all and end-all, which further erodes its cultural authority. The Wall Street Journal calls Gen Z “the Toolbelt Generation” — more young people are choosing plumbing and carpentry over college degrees. The result is that colleges aren’t just competing with each other anymore. They’re competing with the labor market, with alternative credentials, and with the simple choice to skip higher ed entirely. The student I met might simply be making a rational choice that other students could mimic in years to come.

When universities close

This isn’t really a story about enrollment numbers or tuition costs. It’s about what could happen when an entire economic ecosystem built on endless human capital runs out of fuel — and the consequences of the engine stalling.

Universities are the economic engines of hundreds of small and midsize cities across America. When Green Mountain College in Vermont shuttered after 185 years, the town of Poultney lost a school and a $6 million annual payroll, hundreds of young residents, and any reasonable hope for demographic renewal. The school was bought for $5 million and is being turned into condos and a destination hotel.

More than 90 colleges have already closed or merged over the past 10 years, measured in-depth by Higher Ed Dive. One-third of U.S. four-year colleges enroll under 1,000 students, which makes them very vulnerable to even slight drops in incoming freshmen, according to The Brookings Institution. Each closure weakens a local economy and the regional sense of identity.

Universities are economic multipliers:

Student housing drives demand for apartments and home rentals.

College towns have distinct commercial ecosystems built around young people with disposable income and irregular schedules. When enrollment drops, these businesses — like bars, coffee shops, and bookstores — thin out or close.

Universities bring theaters, lecture series, art galleries, athletic events, and public intellectuals to communities that wouldn’t otherwise support them.

Finally, many graduates of regional universities stay local, becoming teachers, nurses, engineers, and small business owners. When the pipeline dries up, communities lose their best chance at attracting and retaining young professionals.

What’s happening to universities is a preview. Higher education is simply the first system to hit the wall of population decline. The same dynamics are coming for the broader economy — shrinking labor pools, supply crunches, and Social Security and Medicare buckling under demographic pressure.

What Could Work

The decline doesn’t have to be death. If we plan well, it can be transformation. At the institutional level, universities can pool services and form regional partnerships. Many community colleges have already succeeded by redesigning confusing course paths, eliminating multi-term prerequisites, and offering guided-pathway structures.

On the community side, state and federal grants could help towns diversify before campus closures by converting empty dorms into vocational hubs, affordable housing, or tech incubators. At the policy level, expanding grants, reducing cost barriers, and recruiting international students can act as partial buffers. There are a few examples to pull from:

Immigration could offset the decline — at least in the medium term. Research from UC Davis economist Giovanni Peri argued that only net immigration can ensure population stability or growth in aging advanced economies, and it has to happen through forward-looking policies rather than short-term political calculations (a tough move at the moment, clearly). The key is increasing the number of immigrants allowed, reducing constraints on immigration, and planning for future inflows. Countries need to actively create channels for migration rather than waiting for market forces.

Community transitions work when planned ahead. When the Huntley coal plant closed in Tonawanda, New York, in 2016, the town formed a coalition including unions, environmental groups, and teachers associations that successfully persuaded state officials to provide transition support. There is power in coordination. In places like Appalachia, former coal infrastructure has been repurposed for renewable energy training programs. Federal programs like POWER (Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization) have helped coal communities transition by redirecting existing resources toward new industries. The model works: Identify underutilized federal or state funds, coordinate stakeholders, and repurpose assets before they become liabilities.

Institutional adaptation matters. Small colleges are pooling services, sharing administrative costs and forming partnerships that let them maintain distinct identities while achieving economies of scale. As the Community College Research Center has highlighted in its work, community colleges have succeeded by eliminating confusing course paths, reducing multi-term prerequisites, and offering guided-pathway structures that help students finish faster and with less debt.

Not all schools will fail. Flagship state universities and elite privates will endure. So will schools with strong football programs — athletics might be the last mass-scale cultural glue universities offer, and schools with ESPN contracts will outlast struggling liberal arts colleges every time.

In the best case, this will be an evolutionary process where the colleges that survive are the highest-value (fittest) of the herd. But that’s only true if the transition is managed, not chaotic.

The difference between managed decline and collapse is planning. The key is starting before the crisis, not after.

The Rust Belt has taught us the consequences of governments refusing to plan: political rage, communities that feel abandoned, and wholesale rejection of the very policies that might help. We let entire regions hollow out, then expressed surprise when those regions turned against the system that left them behind.

College towns are facing the same choice.

The enrollment cliff offers policymakers a rare chance to show they’ve learned something — that governments can plan for difficult transitions rather than just react to them, that public investment can cushion shocks rather than leaving communities to collapse and fend for themselves.

The test isn’t whether every college survives. It’s whether we manage the ones that don’t with enough foresight and support that communities maintain trust in institutions and belief in a shared future.

There are many students like the one I spoke to at WKU, and all of them deserve a reliable pathway to a stable life. It’s up to us to build it.

Universities could be the first American institutions to run out of people. They won’t be the last. The real test is whether we plan for demographic decline with foresight and public investment, or repeat the mistake of the Rust Belt.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the figure about where students admitted to but not attending Western Kentucky University ultimately ended up.

The one forewarned about since Peter G. Peterson’s Gray Dawn.

Great piece. Not a criticism, because that’s not what you set out to do here, but I haven’t seen much written about how young people’s changing choices will affect the trades. Plumbers and electricians command huge wages now (trust me, I’ve had a spate of plumbing issues lately in our 1950s home). Presumably that will change as the supply of them increases, especially in places like rural Kentucky where there’s a finite demand.

Maybe it’s just my algorithm. Probably it’s that the chattering classes are just more interested in writing about college. But I’d love to see an economist or journalist to do some work on kids’ changing choices and the future of the trades … and the cost of home repair!

I’m confused about that initial student. The college wage premium remains high, real tuition has declined over the last 15 years, and manufacturing jobs continue to shrink. Stay in school, kid!