YIMBYs beat the politicians. Now they have to beat the judges.

As legislatures have said yes to new housing, obstacles still remain.

The intellectual fight over liberalizing land-use regulations is over. The YIMBYs have won.

Almost all economists and legal scholars agree that land-use regulations have played a central role in creating a housing crisis, slowing economic growth and increasing economic inequality without producing sufficient benefits. (The few dead-enders out there are increasingly rare.) Politicians of all stripes — from the hard right to the socialist left and all between — at least gesture toward the need for zoning reform.

Only a decade or so ago, arguing that private developers needed a freer hand to build housing was an unpopular take. Arguments that leading political figures should put zoning reform at the center of their agendas would have been seen as totally crazy. Now, even many of the movement’s harshest skeptics are careful to note that they, too, support land-use reform, opposing only the intensity of the focus on land-use reform.

But winning this fight on paper was never the point. The point was to build more housing.

And to do that, we are going to have to take on the NIMBY judges.

These judges are products of local political systems and interest group formations that have proven immune to the sudden changes that have swept much of the rest of our politics. In many cities, there are scores of politicians and interest groups who arrived in power during an era when land-use reform was a topic for economics classroom seminars but not the real world, and for whom opposition to development and developers is still a righteous cause.

In each of the past few years, state legislatures around the country – in red and blue states – have passed a wide variety of land use reforms. But many of these laws have not done as much to expand the housing supply as expected, in substantial part because of local opposition, including from homeowners who think new housing will drive down the value of their homes or change the character of their neighborhoods, renters groups who think new housing will increase neighborhood prices (against all relevant data) and labor, environmental, or community groups who want “everything bagel” provisions that serve as a tax on new housing development.

The intellectual victory of the YIMBYs can sometimes obscure how precarious our position really is: A whole edifice of opposition to land-use reforms is still in place — people in power with formative political experiences and assumptions from a prior era.

These opponents are often able to use extensive local land-use authority to gum up the works — adding high sewer hookup fees or parking requirements to frustrate ADU laws, giving sites historic preservation status strategically, or, once, trying to convince state regulators that an entire town is a mountain lion habitat to avoid a state lot-split law. State policymakers are forced into playing “whack-a-mole,” passing new laws to defeat whatever clever new ruse local opponents have come up with.

These groups are more influential in local politics than they are at the state level (although they sometimes win in statehouses too). At the request of these groups, local governments use their broad powers over land use to frustrate state laws meant to make building easier, adding lots of new requirements or fees in place of preempted ones.

This throw-spaghetti-at-the-wall-and-see-what-delays-construction form of opposition isn’t limited to city councils. We see the same basic dynamic in state trial courts. Minneapolis; Arlington, Virginia; New York City, the state of Montana, and other jurisdictions have seen important land-use reforms stopped by trial-level state court judges.

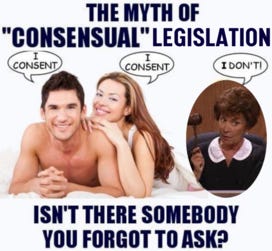

The voters have had their say, the legislators have gotten to vote, and the mayors and governors have weighed in. But there’s still one other person you forgot to ask: your state trial court judge.

State trial court judges have found every type of excuse to hold up pro-housing reforms, despite repeatedly being reversed by appellate courts. These judges are products of local political systems and interest group formations that have proven immune to the changes that have swept much of the rest of our politics.

Sometimes these judges’ decisions have been hyper-legalistic and niggling, like when Judge David Schell halted Arlington’s recent “missing middle” zoning reform for failing to pass an “initiating resolution.” Schell rebuked the local legislature for failing to advertise the fact that reforms were being considered before proceeding with the law (not that anyone interested hadn’t heard about them) and for failing to study localized environmental effects like stormwater spillover (although a county expert testified that the infrastructure was sufficient).

In other situations, these anti-development decisions have been anything but legalistic. For instance, before Judge Arthur Engoron stopped construction of a big project on the Lower East Side in New York City, he reportedly stated in open court: “These are huge towers. I’ve lived in the city my whole life. You can’t just do this because the zoning allows it. I just can’t believe this is the case.”

A Montana trial court granted a preliminary injunction against a state law that preempted local regulations on accessory dwelling units. The court argued that the law violated the equal protection clause and there would be irreparable injury if it went into effect. Why? Because some homeowners were part of private homeowners associations that didn’t allow accessory dwelling units and others were not. (I promise it did not make more sense than that!) And the irreparable injury was because, absent an injunction, a homeowner “could wake up one morning to find that, without any notice at all, a new duplex or ADU (accessory dwelling unit) is going up next door in their previously peaceful and well-maintained single-family neighborhood.” Quelle horreur.

All of these decisions were reversed, as was a trial court decision delaying Minneapolis’ widely lauded “2040 Plan.”

But, even when higher-level courts reverse trial courts, the cost of dealing with such a long and arduous legal battle is a huge deterrent to developers and elected officials who seek to build more housing and upzone their cities. Indeed, despite winning in court eventually, New York’s Two Bridges project — which was supposed to create 1,300 new homes — is not going forward.

Housing delayed is housing denied.

For a movement focused on speed, committing to rooting out every single NIMBY judicial decision may feel hopeless. But there is a path forward.

The consistency with which these NIMBY decisions are reversed makes clear that they are not required by law. Instead, their opposition is rooted in something structural about the politics of state court judges. Like many problems identified by abundance liberals, local democratic institutions are at the root of the problem.

For instance, in New York, trial court judges are elected, but only through a weird two-stage process that effectively means that county party chairmen choose the judges. Brooklyn’s Democratic Party famously holds its judicial selection meetings in an out-of-the-way restaurant called Nick’s Lobster House. The process is so strange that the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at one point decided it was unconstitutional before being reversed by the Supreme Court.

We expect city council primary elections held off-cycle to produce officials who represent the voters who show up in those types of elections — older, richer, and far more likely to be homeowners. Judges selected by county party chairs represent the same type of politics. In New York, the governor selects appellate judges, and thus they tend to have different assumptions and beliefs.

In other states, the process is less strange, but the basic dynamic is the same. Montana elects judges in nonpartisan elections at both the trial and appellate levels. The Supreme Court elections are high-profile and competitive, however, while the trial-level elections rarely see any competition.

Trial court elections in Minnesota are almost never competitive either. Virginia has a system that dates back to when the state was dominated by the segregationist Harry Byrd’s political machine. The state legislature chooses the judges, but there is a long-standing practice of deferring to legislators from particular districts, a version of the same type of member deference that leads city councils to allow local members to decide on zoning changes in their districts.

While the systems differ, there is a broad consistency that trial court judges emerge from low-salience parts of local political cultures. These are the parts of our legal system that are least likely to be touched by ideological changes. And state laws — from state environmental laws to the complex procedures put into land-use law — give them plenty of discretion to find ways to frustrate newly emerging political will to reform zoning regulations.

As I’ve argued in many places, this is a product of the mismatch between where government power resides in America — often in local institutions — and our increasingly nationalized politics. Given the decline of local media and the nationalization of our political parties, local legislative and judicial elections cannot represent shifts in popular opinion, nor do they appropriately hold local legislators accountable for policy outcomes. Their low-information, off-cycle elections allow narrow groups of homeowners and interest groups to dominate.

The only way out is through. Local opposition frustrated California’s first several efforts to make local governments approve ADUs. But the state legislature repeatedly passed laws to overcome local opposition, and now the state has a boom in ADUs, the most exciting development in California housing in years.

States can do something similar with respect to state court resistance. Some of these decisions are based on skepticism about mayoral power, echoing the Supreme Court’s rejection of so-called Chevron deference to executive branch interpretations of federal laws. Interpretations of zoning codes by city planning departments are treated with skepticism, allowing judges to substitute their judgment for that of officials appointed by mayors.

Higher-level state courts should reject this move for local governments — and the even more aggressive local nondelegation doctrine — and provide more politically responsive mayors and planning boards with substantial interpretive authority over local laws. State legislators can also reduce judicial discretion by removing infill housing from some or all state environmental reviews, and, more broadly, by regularly updating state land-use laws to make them ever clearer.

There are limits to any effort to solve either problem once and for all. Absent something truly radical happening to the basic structure of local land-use authority, we’re all essentially playing whack-a-mole with the countless ways people can block new housing. The key for land-use reformers is having enough political staying power to get laws passed in successive legislative sessions — to whack enough moles that housing can eventually get built.

This is why the growth of powerful political groups like California YIMBY and similar lobbying groups and think tanks around the country is so essential. Only by institutionalizing the idea that states need more housing can local opposition to building be worn down.

The same thing is true in the courts. There’s no legislative response to a judge who says that he opposes a new project no matter what the zoning law says. While individual developers can and will bring suits for big projects, the hand-to-hand fighting in the courts needs institutions.

Both left-leaning litigation shops like YIMBY Law and right-leaning ones like the Institute for Justice and the Pacific Legal Foundation have brought repeated suits appealing and defeating NIMBY state court decisions. These groups can keep up the fight, while local YIMBY-oriented groups vie for influence in trial court judicial nominations.

YIMBYs have gone after the zoning boards, community boards, party committees, statehouses, and governors’ mansions. It’s time to take on the courts.

As a California voter who usually has zero relevant information on judges on the ballot, I would welcome endorsements or opposition statements from YIMBY groups.

There is some repeated text in the post, eg:

> there are scores of politicians and interest groups who arrived in power during an era when land use reform was a topic for economics classroom seminars but not the real world, and for whom opposition to development and developers is still a righteous cause.