A lot of people are way too eager to declare Mississippi a myth, part I

A response to an alleged debunking

Jerusalem will be answering reader questions on a special “Ask Me Anything” episode of The Argument podcast. If you’re interested in asking a question about building a new publication, liberalism, housing, NIMBYism, politics, or anything else, send a voice memo to podcast@theargumentmag.com.

When there’s a scandalous “false miracle” in the education world, it’s usually one of two things: direct cheating on a test or careful selection of the population that takes the test. So if you see a sizable improvement in education results, it’s worth looking out for both of those.

When I first began looking into the “Mississippi Miracle,” wherein a low-performing southern state shot up in fourth-grade reading scores from 49th place to ninth place, I was worried about being taken in by yet another fraudulent success story in the world of education. So, I tried to figure out: Was I looking at education, or was I looking at selection?

In particular, a major plank of Mississippi’s reading reforms is a test of basic reading fluency administered at the end of third grade. Kids who don’t pass it are held back a year. For at least five years, people have argued that maybe this, rather than any actual teaching skill present in Mississippi, is what’s driving the state’s improvements.1

A provocative new article from Howard Wainer, Irina Grabovsky, and Daniel H. Robinson in Significance argued that, in fact, nearly all of Mississippi’s results are driven by the third-grade retention policy, not by the phonics instruction, curriculum changes, or the teacher training that accompanied them. It has gone viral, with lots of glee in certain quarters, where it was sometimes taken as proof that there’s nothing other states need to learn from Mississippi after all.

This is an important debate, but I’ve been dismayed to see their article treated as a significant contribution to it. It’s badly mangled with straightforward factual errors that should undermine anyone’s confidence the authors did their homework — for example, the authors claimed that “the 2024 NAEP fourth-grade mathematics scores rank the state at a tie at 50th!” In fact, Mississippi ranked 16th on the fourth-grade math NAEP assessment.2 Unsurprisingly, the authors’ errors are not limited to these sorts of factual claims but also extend to their core argument, which is wholly unpersuasive.

The debunking of the Mississippi Miracle largely rests on the only piece of mathematical analysis that Wainer et al. did: where they looked at what happens to the state’s average reading scores if you truncate a dataset — that is, drop a bunch of the lowest performers. They then looked at Mississippi retention data.

Strangely, the paper treated holding back 5% of students as identical to truncating the lowest 5% of test scores. But those are two different things, which makes their conclusion, that truncating the scores would be sufficient to explain Mississippi’s gains and therefore that other reforms played no role, invalid.

Hopefully you’ve noticed the problem: A student that repeats the third grade does not conveniently vanish off the face of the earth. They just … take third grade again, and then they move on to fourth grade. The state still tests them; they just do so a year later.

Wainer et al.’s mathematical analysis doesn’t look at what happens when you delay students one year, it looks at the effects on overall test scores of *vanishing* the bottom 10% of students. Which obviously didn’t happen. And indeed, if you kicked all of those students out of public education, it would increase your average test scores by about as much as Mississippi’s test scores have increased.

In other words, the skeptics successfully showed that if Mississippi had kicked out the bottom 10% of their class, the effect size would match reality.

Therefore, they say, there is nothing left to explain: “the lion’s share of the effects of the ‘Mississippi miracle’ are yet another case of gaming the system. There is no miracle to behold. There is nothing special in Mississippi’s literacy reform model that should be replicated globally. It just emphasises the obvious advice that, if you want your students to get high scores, don’t allow those students who are likely to get low scores to take the test.”

This summary would be precisely accurate, and the assumptions in their analysis would all hold, if Mississippi were expelling from school all of the students who fail the third-grade test.

That’s not what’s going on at all. If a student is held back a year, they still take the test again when they do reach fourth grade, a year later. Under Mississippi’s retention law, a student can usually only be retained for a maximum of two years.

They will still go on to fourth grade and therefore still take the test. This makes Wainer et al.’s entire analysis of how the mean shifts in a truncated dataset void.

Now, obviously, there is still a worthwhile analysis to be done here. It’s not the one they conducted, so we’ll have to conduct it ourselves.

What happens if you hold back the bottom 10% of students, giving them an extra year to learn to read? Their scores will be higher because of the extra year of opportunity to learn the material.

The effects of this will probably not be as large as the effects of excluding them from the test entirely, since they are unlikely to improve at reading so much as would actually be required to increase the class mean. But the effects will still exist, and it still might explain much of the improvement in Mississippi’s reading scores.

If this were true, it wouldn’t exactly be a scandal. The idea that “Mississippi doesn’t advance students until they’re ready, and so a student in fourth grade in Mississippi is a stronger reader than in other states, even if Mississippi 10-year-olds are average” is … good? But it would mean that much reporting about Mississippi — including mine — was wrong.

I previously wrote that the retention policy, the adoption of a strong phonics-based literacy curriculum, teacher training on how to best use the curriculum, and other reforms all played a role in what happened in Mississippi, and that other states can imitate them. If it’s all retention, then there’s nothing to be gained by imitating any of the rest.

Is there any way to tell whether Mississippi is doing anything right beyond holding back unready students? Here is where it is useful to break out the NAEP results by decile.

If all of Mississippi’s gains were from the bottom 10% of students being held back and then getting to take the test a year later, when they’re stronger readers, we might expect that most of Mississippi’s gains are concentrated in the bottom decile (among the weakest students). We would not expect the strongest students to be affected at all — none of them are held back, and almost no child is going to go from bottom 10th to top 10th in a single year.

The NAEP publishes test scores broken down by decile. And what we see is that Mississippi has seen gains in every decile. To be a 10th-percentile student in Mississippi, you would need a score of 157 in 2005 and a 170 in 2024. For a 50th-percentile student, the bar moved from 206 to 222. A 75th percentile student? 230 to 245. A 90th percentile student? 249 to 262.

Those latter results cannot be explained by the fact that some of the low-performing students were held back, so long as the low-performing students are not excluded from taking the test at all. They could be explained if the low-performing students were excluded from the test. But this isn’t happening.

This is not the only problem with trying to attribute Mississippi’s gains purely to retention. Mississippi has been gaining ground steadily for two decades, so any explanation for their results needs to explain steady gains, not a one-off jump.

Much of Mississippi’s rise started before they changed their third-grade retention policies (which they did in a 2013 law, first fully in effect in 2015). Even if you think all of the continued improvement since they changed third-grade retention is attributable to the change in retention policies, you should be curious what they did before then!

Furthermore, when a trend line doesn’t seem to bend in 2015, you should be suspicious of any story that says the driver of the trend line is something that happened in 2015. And even post-2015, the gains continue year-over-year, rather than being discontinuous — for the gains to be explained by more students getting held back, Mississippi would have to be holding back a growing share of students. They aren’t — the share of students who failed the reading test and were retained varies a lot but dropped from 2018 to 2022, from 9.6% to 7.2%.

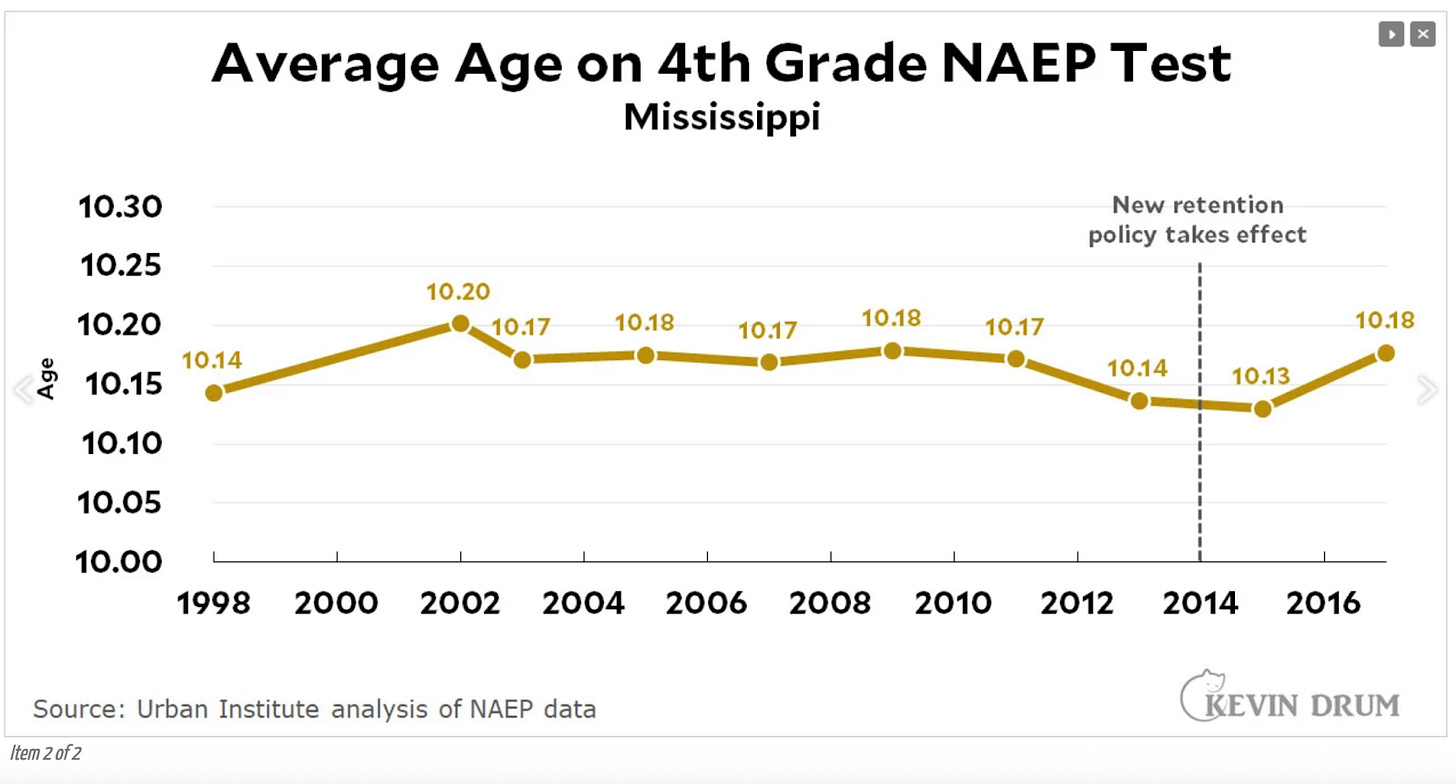

Lastly, in 2019, when this controversy first reared its head, some researchers looked at the average age of students in Mississippi taking the fourth-grade test. They found that the average age in Mississippi is higher than in many other states — Mississippi holds more students back from the next grade than most states do — but that it has not risen since 2000. That’s at least a bound on how much retention rates could have increased.

Now, this data only goes through 2017. It’s possible that since then, Mississippi has started holding back more students (especially after the pandemic, which we know impacted student preparedness). But at minimum, none of the gains through 2017 can be attributed to holding back more students.3

For all of these reasons, while weaker students having an extra year to learn to read is almost certainly contributing to Mississippi’s scores, it cannot explain Mississippi’s gains since 2003 — or even much of Mississippi’s gains since 2013.4

Wainer’s article also seems to want to have its cake and eat it too when it comes to the fact that 2013 is not a particular turning point in Mississippi’s results. At one point, the authors pointed out that the trend line didn’t change in 2013 in order to refute claims that the 2013 reforms worked.

This is convincing if you previously thought the 2013 package was the primary cause of Mississippi’s gains. If you think that Mississippi has been doing a lot of reforms, of which the 2013 reform package is notable but not exclusive5 — then you wouldn’t necessarily expect a discontinuity in 2013.

On the other hand, by the terms of Wainer’s own argument that these gains are purely a consequence of holding students back, you really should see a discontinuity in 2015, when the new retention policy kicked in.

Jerusalem made me split this article in two because it was so long. To receive part II in your inbox later today, subscribe! It includes my best case for why I could be wrong … and why I think I’m still right anyways.

Now, if Mississippi were getting great results just from holding unready kids back one year, this wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing! Holding kids back until they’re ready for fourth grade might still be good policy! But Mississippi’s success has been presented — including by me — as the product of a bunch of reforms, including third-grade retention but also including phonics, better teacher training, better curriculum, and more support at low-performing schools. If all of the gains were coming from third-grade retention, then this story is at minimum being mistold.

This is one of the oddest of the many errors in the piece. The fact that Mississippi fourth-graders are also strong in math doesn’t even undermine the authors’ main argument, which is that if you hold back a lot of the weakest third-graders your fourth-grade scores will look better. In the full context, the point just seems to be expressing loathing for Mississippi: “The 2024 NAEP fourth-grade mathematics scores rank the state at a tie at 50th! The eighth-grade scores also qualify for 50th place. This is certainly consistent with the Mississippi that most of us know,” the authors wrote. The eighth-grade scores don’t qualify for 50th place; they’re 35th, though if you adopt the controversial approach of adjusting for demographics, Mississippi emerges as number 1 (that is, the Mississippi that the authors know is not the one in the data).

To their credit, when I reached out to the authors about this mistake, they acknowledged it immediately and reached out to get it fixed before the article’s publication.

But, some people have argued, maybe they can be attributed to holding back different students. Maybe before 2015, Mississippi was holding back students selected some other way, and they switched to holding back the weakest readers. This doesn’t make a lot of sense to me — Even if there weren’t statewide standardization on exactly where the threshold was, surely the state was not holding back students who were academic strong performers. And surely if the 2015 policy marked a significant change, there would be a discontinuity in 2015, which there isn’t. And in any event, the students who are held back are readded.

There is one creative way that Mississippi’s gains could be explained through student retention: The NAEP is every other year. If the state holds back more students the year before an NAEP test year and then lets them through in a year with no NAEP, that would let the state fudge the numbers. But we have Mississippi’s year-to-year retention numbers for some recent years, and no such trend is present. In 2022, the state retained 9.6% of students in a year where that fourth-grade cohort would take no NAEP (there was no 2023 NAEP). In 2023, it retained only 7.2% of students in a year where that cohort would take the NAEP (which it did take, in the 2024 school year, and performed well on.)

There are also a bunch of No Child Left Behind-related changes in the 2000s: a 2015 change to state standards to match NAEP standards, a 2016 change to teacher licensing, a 2017 requirement for dyslexia screening, and expansions of reading exam requirements and standards in 2021 and 2023.

I’m pretty confident the knee jerk skepticism about the “Mississippi Miracle” is the result of the immense psychic injury a lot of blue staters suffered from having to entertain the idea that a bunch of dumb hicks are doing something better than they are.

At this point like 10% of my media consumption is Kelsey Piper pointing out that Mississippi did actually meaningfully improve education outcomes and Andy Masley pointing out that data centers don't actually use very much water. I'm awed at their persistence in the face of such poor epistemics on the part of their opponents and annoyed that this much effort is required to even put up a decent flight against pervasive motivated reasoning.