Below the $140,000 "poverty line"? Give anyway.

A few hundred dollars isn't going to change how financially strapped the upper middle class feels.

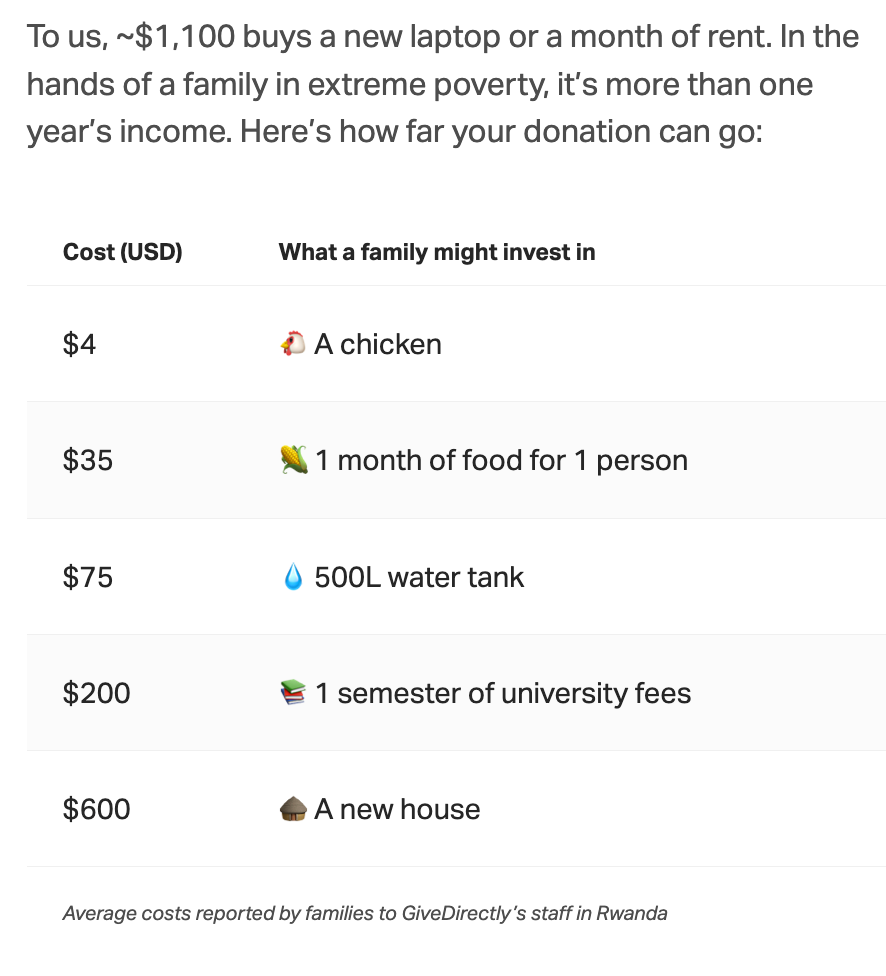

Today, The Argument, alongside 31 other magazines, newsletters, and independent media companies, is raising money for GiveDirectly. Our goal is $1 million total (up to $600,000 will be matched). Meeting that goal will mean putting ~$1,100 directly in the hands of more than 800 Rwandan families. Funds will let recipients purchase things like a water tank ($75), a semester of university fees ($200), a new house ($600), a month of food ($35), and more.

Lots of people are asking for your money today. If you want your donation to make a real difference in the life of someone who needs it the most, I cannot think of a better place to donate than GiveDirectly.

As a mark of my newfound ability to disconnect from social media over the holidays, I didn’t come across the $140,000-is-the-new-poverty-line discourse until Sunday. So, for the similarly unplugged, here is a recap:

Michael Green, an asset manager with a newsletter, looked into how the poverty line is calculated and discovered that the poverty threshold is set as three times the cost of a minimum food diet in 1963.

This measure was selected because, at the time, food at home was roughly one-third of household spending. But Green pointed out that in 2024, food at home was roughly 5% to 7% percent of household spending1.

Green then recalculated the poverty threshold by multiplying the cost of a minimum food diet in 2024 by 16 rather than three, reflecting the fact that food had declined as a share of household spending. That means the modern poverty threshold goes from $31,200 to $136,500.

At this point, a reasonable person might think twice about this finding. After all, a poverty line of almost $140,000 would capture the majority of American households. Green does not appear to have thought twice, and soon his new “poverty line” had gone viral.

That an American family earning $130,000 should be considered poor is the kind of commentary produced by an outlet whose readers are comfortably in the upper middle class of the wealthiest nation the world has ever seen. At one point Green even recognized this; without a hint of self-awareness he noted that “most of my readers will have cleared this threshold.” I’m sure they have!

One of the most frustrating things about the ensuing discourse is how much it became about being “directionally correct,” which actually has nothing to do with being correct at all and simply means viewing every discussion as a proxy battle in another fight where the sides have already been picked.

So, instead of evaluating the already complicated question of what the poverty line is or means or should be or should mean, the debate becomes yet another battle about whether you are for or against the status quo; neoliberal or postneoliberal; irritating know-it-all wonk-brain or salt-of-the-earth Real American.

One of the negative side effects of seeing every minor dispute as obviously being about a larger, more important battle is that it makes it impossible to create a set of shared facts or find agreement among unexpected sources. For instance, I have many disagreements with AEI’s Scott Winship about optimal welfare policy. But both of us can look at the question about poverty measurements in 2024 and conclude that no reasonable, intelligent inquiry could end with the phrase: Poverty means making $130,000.

No one needs another post about the many ways that Green is wrong. Others have already pointed out Green’s fatal arithmetic errors (the multiplier should be 7.6, not 16, which makes his new poverty measure $81,000, not $135,000) not to mention his various conceptual errors so I won’t spend a bunch of time on them. Feel free to read those links if you’re interested in the whole back-and-forth.

But today I’m asking you to donate your money to people who are much poorer than you, so I want to engage in the meta-debate.

Why should you give money to people even if you’re struggling to meet your financial goals?

Putting aside the question of poverty, most people want more money to meet various goals, needs, or wants. Whether it’s buying a house, saving up to visit your brother on his birthday, paying for child care, or purchasing piano lessons for your kid, there are lots of reasons why someone who isn’t “poor” could feel financially strained.

I don’t want to berate you if you’re in this position. Yes, you are richer than most everyone else in the world, but you know that. Yes, generosity is a virtue, but you know that. Yes, life could be worse, and you know that.

There’s no dispositive research I could find on this, but what I did find supported my general sense that people who feel financially strapped are less likely to be generous with their resources.

There are a lot of good articles pointing out that even a pretty average income in the United States is earth-shatteringly wealthy in other parts of the world (here is my favorite), but I think that sort of thing can ignite feelings of shame or denial in people who are struggling to afford presents for their kids or are worried about their winter heating bills.

Part of why Green’s article did so well is that even people who are very rich by world standards can and do feel financially strained and people who are under stress often look for validation. That’s pretty understandable!

I want to speak directly to the folks in this bucket. To people who know objectively that they’re doing pretty well but still feel like they’re barely scraping by:

You should give your money to rural Rwandan subsistence farmers because you can’t actually meaningfully help solve the affordability problems of middle- and upper-middle-class Americans with a few hundred dollars. However, you can help solve the problems of the world’s poorest people with a few hundred dollars.

Let’s start by taking your personal concerns seriously: The financial problems middle and upper middle income families face in the United States are largely not about income, they’re about policy. Yes, a few hundred could help for the holidays or to defray some bills for a $130,000 household, but it’s not going to fundamentally change the circumstances that make those families feel financially strained. That’s almost entirely about housing.

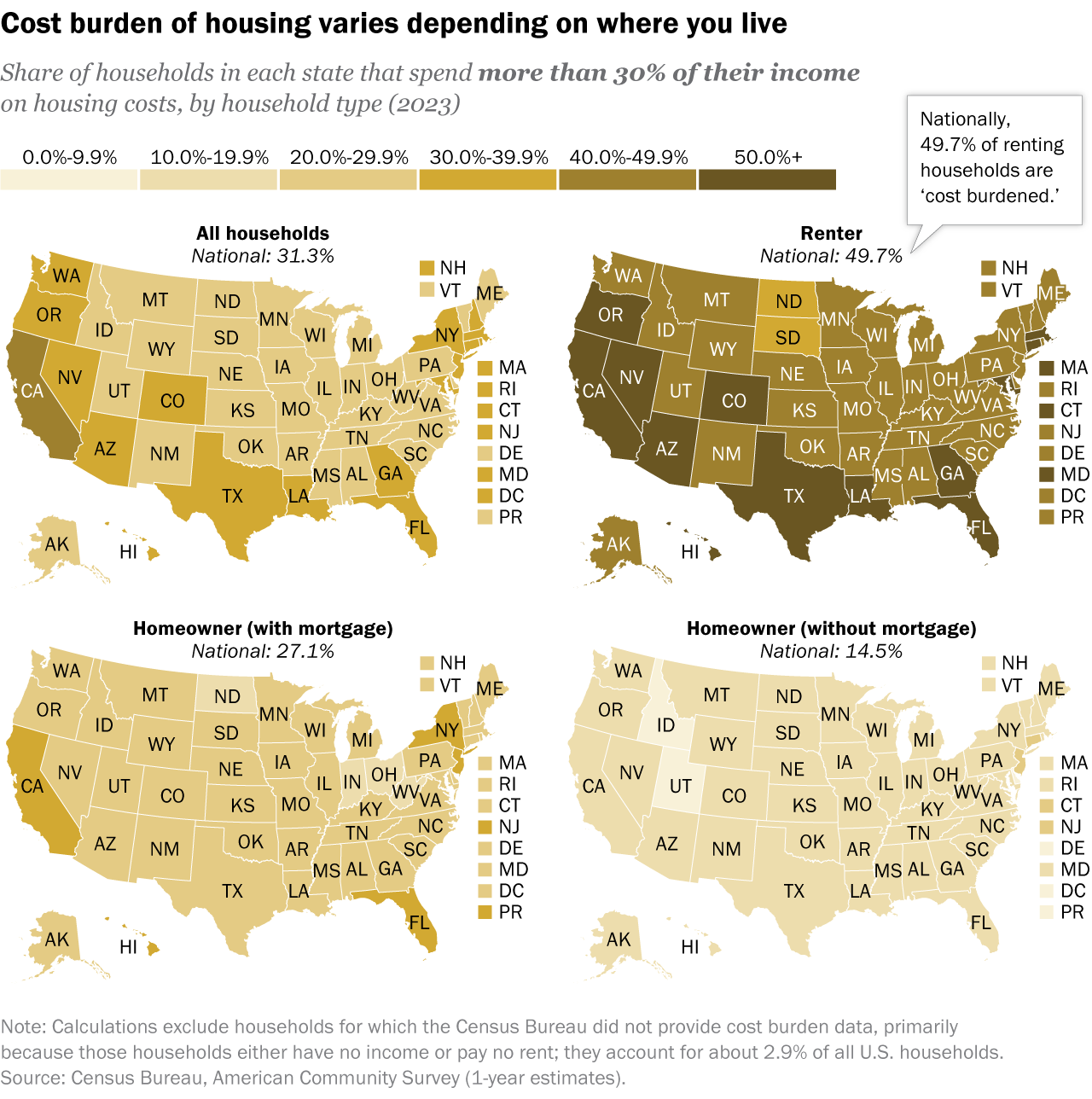

Throughout Green’s post, he pointed to the debilitating cost of shelter, and he’s right. More than half of renting households are spending over 30% of their household income on rent, and more than a quarter are spending over half of their household income on rent.

A family of three earning $130,000 a year cannot afford to buy a two-bedroom home in Brooklyn. They would be in a slightly better position if they worked and got to $140,000 or $150,000, but fundamentally, housing costs in Brooklyn are too high. They are too high because of decades of underbuilding caused by an anti-growth political coalition that has hijacked high-productivity cities and suburbs. Whether or not this family has a few hundred or even a few thousand extra dollars isn’t going to make a life-changing difference.

It’s not going to be what stands between you and homeownership or between you and a house with a guest bedroom.

Think about it this way: If half the homes in the United States suddenly disappeared tomorrow, would it solve the problem if each household got an extra $10,000 or even $20,000? No, you could only really solve that by building a bunch more houses. Money can’t buy what doesn’t exist.

Lots of policy questions are hard, and no, you can’t “solve” all housing problems by eliminating anti-growth regulations. But land-use regulations that have no relationship to health and safety could be eliminated by a grad student and the Ctrl-F function going through various zoning codes and deleting anything that mandates a minimum number of parking spots or minimum lot sizes. Hell, I would do it for free.

The problem with thinking, as Green does, that this constitutes an income problem is that you end up supporting demand-side policies that make the problem worse. For instance, if the problem of housing affordability is that people don’t have enough money, then the solution is obvious: Give them money!

So what happens when we give low-income renters money for rent in supply-constrained markets?

A very well-done study from 2013 looked at what happened when the government gave out more housing vouchers. The researchers found that in the relevant, supply constrained segments of the housing market where housing voucher holders were seeking housing, rents increased. Other research has found the same directional effect.

And this is in the place where demand-side explanations make the most sense. Yes, we need to build more affordable housing, but very-low-income renters are facing financial constraints that require demand-side solutions.

It’s even more absurd to realize how many policymakers are trying to solve problems of middle class and upper middle class housing affordability through demand-side subsidies. When I’m 70 years old, I’ll still be hearing about President Barron Trump’s push to give downwardly mobile WASPs downpayment assistance.

You can’t buy a house for $600, but a family in Rwanda can

Here is a list of things Rwandan families say they can buy with your donation:

GiveDirectly isn’t just finding random poor people and giving them money. Part of what makes this organization worthy of your funds is how seriously it takes finding the places where your dollars will go furthest. They have identified the “poorest regions and most vulnerable households in Rwanda” using government census data. These are folks living on less than $1 to $2 a day.

GiveDirectly staff go door-to-door and enroll each household into the program, after which they send the funds through SMS banking technology. GiveDirectly also audits its program by calling individuals to ensure they received the funds.

It is transparent and open about how much of its funds are lost to fraud, a practice that makes me trust that charitable donations aren’t being lost to bad actors in these regions. You can read more about how its fraud team operates — it’s pretty intense: pseudonyms, secret work locations, and no work branding.

I hope I’ve convinced you. Life may be hard for you; I don’t want to pretend I’ve never felt financially strained, even in my own privileged position. But giving away a tiny fraction of your income is not going to fundamentally change how hard it feels.

In fact, I expect you’ll feel a lot better — giving to charity comes with a dose of smug self-satisfaction. And what could be better than that?

He was wrong, it’s actually 4.9%.