Coping with Christmas

Christmas is alienating and Hanukkah is shallow. What’s a Jew to do?

Merry Christmas to all who celebrate! The Argument doesn’t publish on major holidays but after our fastidious copy editor Eli Richman pitched this piece, I thought it would be deliciously ironic to publish on today of all days. Now, an essay for those who don’t celebrate… - Jerusalem Demsas, Editor-in-Chief

Christians often understand Jews to be more or less the same as them, so long as you ignore a strange aversion to bacon and switch some keywords around: Synagogue instead of Church, Torah instead of Bible, Rabbis instead of priests or ministers or whatever else you call a Christian cleric, and … Hanukkah instead of Christmas.

This last one is, in my opinion, the worst offender of the bunch.

Hanukkah is not to Jews what Christmas is to Christians; we are talking about a minor holiday that was deliberately redesigned and eventually promoted to provide a satisfactory alternative to Christmas. A coincidence of timing has forever put the two holidays in contention with each other, but Hanukkah is so ill-suited to serve as “Jewish Christmas” that we have needed to devise an entirely separate group of traditions to serve that role.

“Christmas is the most important Christian holiday, so Hanukkah must be the most important Jewish holiday, right?”

Hanukkah is not mentioned in the Torah.1 It is certainly not in the top three most religious holidays for Jews,2 and depending on your point of view, may not be competitive until at most seventh-place.

It’s not even obvious that Hanukkah should be a religious holiday at all. Today, people throw around the word “miracle” a lot, but the story is fundamentally a historical event:

This supposedly “Great” guy Alexander purportedly gave Judeans (proto-Jews) some assurance of autonomy and freedom of religion, but this message didn’t get through to the local Seleucids. So they tried to oppress the Judeans, a fundamentalist group called the Maccabees arose to fight them off, some stuff happened with some oil,3 and the Judeans managed to keep running their temple the way they wanted for another 100 years until the Romans came along and destroyed it.

Interesting in a sort of “I think about the Roman Empire every day” sort of way — and existential in a quite literal sense — but not exactly fuel for spiritual ponderance. And certainly no match for “Our messiah was born on this day 2,000ish years ago.”

“How humble and insignificant does one appear by the side of the other,” Rabbi Kaufman Kohler wrote in The Menorah in 1890, according to My Jewish Learning.

So how did this historical curiosity become the “Jewish counterpart” to one of Christians’ most important holidays? Well, being close together on the calendar certainly helps, but the rest was no accident.

President Ulysses S. Grant established Christmas as a federal holiday in 1870. As it became increasingly commercialized throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the holiday also became impossible to avoid, and Jewish parents and religious leaders feared losing their youth to the oppressive lures of Christmas.

The commercialization of Hanukkah began in the late 1920s, after the largest wave of Jewish immigration to the U.S. had already ended. Like all the best things in life, this started with capitalists trying to identify new markets:

Before then, Hanukkah wasn’t really a big gift-giving holiday. Relatives would hand out money, trinkets, and candy, but the idea of “eight nights of presents” only took off in response to the omnipresence of Christmas; if Jewish kids were getting presents for Hanukkah, they wouldn’t be upset about not getting Christmas presents, the thinking went.

The big tell here is that in Israel, one of the few places in the Western world where Christmas is not pervasive, Hanukkah is much less of a focus — and often doesn’t include gift-giving. Israelis also tell the story differently, focusing more on the secular military struggle and less on the miracles.

“The original Chanukah was a celebration of military victory, and the Talmudic Rabbis reworked it as a primarily spiritual message. Modern Israel refocused on the ‘original’ theme in order to emphasize the idea that Jews could be self-defenders and not only oppressed victims,” Rabbi Lester Bronstein told me via email.

In short, American Jews’ answer to our December dilemma was to take a minor holiday that happened to be close on the calendar and, in the span of a few decades, transform it into a major holiday. But major holidays are supposed to have strong traditions and customs, so Hanukkah needed to have those as well. And the customs we built up around our chosen alternative leave something to be desired.

Eight repetitive nights

Hanukkah can be a bit frustrating to celebrate. The rituals are nice, but the thing is famously eight nights long. So you light the candles and say the blessings and eat the food, then you do the same thing the next night, and the night after that, and the night after that ...

I remember growing up and hearing Christian kids say this sounded great. “Wow, eight days of presents!” But coming up with eight good, thoughtful presents is a lot to ask from parents — especially for more than one kid, especially for multiple years. So what kids often get is one or two nights with good, thoughtful presents and a bunch of nights with fluff: socks, candy, school supplies ...

Or, if you’re neither a child nor a parent, you often just celebrate for a night or two and forget about the rest.

Outside of some rare popular triumphs, there are no good Hanukkah songs. I have lots of musical relatives who will take any opportunity to sing, and they always try to find new Hanukkah songs to break out after the usual blessings. These are some very good singers, and still the songs are inevitably bad: childish, repetitive, lacking compelling melody, lacking meaningful lyrics, or (usually) some combination thereof.

The movie situation is also dire — there are no movies about Hanukkah that are worth rewatching every year a la Miracle on 34th Street or A Christmas Story.4

Adam Sandler’s efforts to correct this are commendable, in a way, between Eight Crazy Nights and endless rewrites of “The Chanukah Song.” But both of these are explicitly contra-Christmas projects. “The Chanukah Song” starts with a verse about how it needs to exist because there are so many Christmas songs and then spends the next few minutes identifying Jewish celebrities.5 Eight Crazy Nights, a film that usually fails to break into the top 10 Adam Sandler movies, has a poster that includes a Christmas tree, a reindeer, Christmas lights, and ornaments, alongside the menorah.

No one knows when Hanukkah is. This is hardly unique — Judaism’s dependence on a lunar calendar means all its holidays jump around for us crazy Gregorian Calendar kids. But it certainly complicates its status as a Christmas alternative when it usually doesn’t fall on Christmas.

But all of this pales in comparison to my biggest gripe, as a professional copy editor: No one knows how to spell Hanukkah.

To a certain extent, this is a problem with transliterating a word in any language that doesn’t use the Latin alphabet, but we’ve figured it out for most other Jewish holidays. AP Stylebook prefers the spelling beginning with H and containing two Ks, but I always learned the word needed to start with “Ch” to represent the guttural Hebrew “chet” sound. Most people don’t follow stylebooks or Hebrew School guidance, so modern spellings are all over the place.

So given all of this, if Hanukkah doesn’t offer Jews a sufficient alternative to Christmas, what does?

Jewish Christmas: A grassroots alternative

Assuming it is not also Hanukkah, the question of what to do on Christmas as a Jew is both delightfully open-ended and somewhat alienating. You’ve got the day open and can spend it pretty much any way you want with no judgment. Spend the whole day napping? Fine. Go on a skiing trip? Brilliant. Volunteer? Amazing. Drink? Why not?

There’s no obligation of how to spend that time, so just pick an activity (or lack thereof) and the people you want to do it with (or lack thereof) and go nuts. But when almost everyone else is occupied with meaningful rituals and family time, whatever you end up doing can serve as a reminder that you’re simply not like most Americans.

It’s a dilemma: We can do basically whatever we want, but nearly every option will contain reminders of our otherness. So what’s a Jew to do? Well …

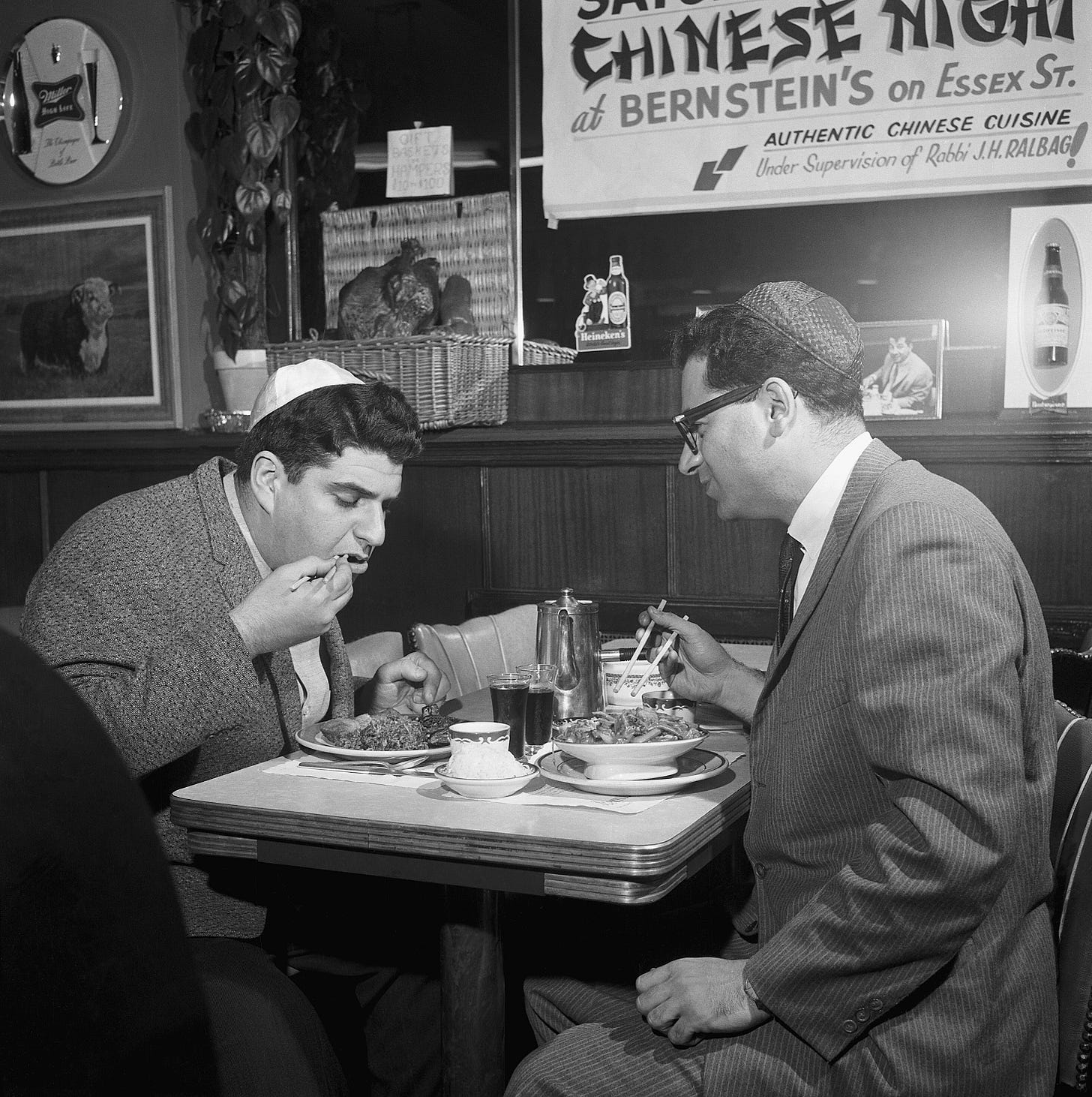

Jews eating Chinese food on Christmas is one of those things that makes perfect sense until you start thinking about it. The first mention of the practice can be found in an 1899 American Hebrew article, which criticized Jews for eating out at non-Kosher restaurants, specifically singling out Chinese restaurants.6

Most accounts trace the phenomenon back to a few broad reasons that originally made Chinese restaurants a good fit for Jews:

Many restaurants close on Christmas, but Chinese restaurants stay open. “The Jews and Chinese were the two largest non-Christian immigrant communities in America,” Jennifer 8. Lee, author of The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food, told Forward. “They didn’t keep a Christian calendar so their restaurants were open on Christmas.”

Chinese immigrants saw Jewish immigrants as more westernized and assimilated than themselves, which was a comforting environment for Jews feeling estranged from their neighbors.

Most Chinese food lacks dairy, which makes it easy to obey the Kashrut prohibition against mixing meat and milk.7

In the early 1900s, common eateries in American cities included those with German, Italian, and Chinese cuisines. Many Jews understandably did not feel comfortable eating at German or Italian restaurants due to the growing antisemitism in those countries at the time and their tendency to include Christian iconography in their decorations.

These days, it’s more common to see Chinese food restaurants festooned with Christmas decorations. But tradition begets tradition, and by the time the 21st century rolled around, eating Chinese food on Christmas was practically as standard a practice as anything Jews do on Hanukkah. Some denominations of Judaism insist seeing a movie is also part of the ritual, but I’ve never met an American Jew who didn’t acknowledge the Chinese food mandate; to deviate now would be heresy.

So in some sense, the December dilemma is already solved: We figured out our own Christmas-alternative traditions, and they have nothing to do with traditional Christmas and nothing to do with traditional Hanukkah.

If Hanukkah isn’t important, what is?

I’ve been harsh to Hanukkah throughout this essay, but it didn’t ask to be put in this position. Holding it up as the Jewish alternative to Christmas does a disservice to Hanukkah more than anything else. The original traditions aren’t sufficient to perform that role, so we’ve had to stretch them out of shape and invent new ones to make it fit.

And one thing I will say about the season is that it’s nice when non-Jewish communities want to include us enough to learn what we’re celebrating and make an effort to acknowledge it. Like with many gifts, it’s the thought that counts.

But the best Christmas present you could give us is to take the effort you would have put into recognizing Hanukkah and save it for next fall, when Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur roll around.

On Sept. 12 next year, wish your Jewish friends a happy new year,8 and ask your Jewish employees if they need to take off work. On Sept. 20, wish us an easy fast and forgive us for being testy the next day — do not utter the words “Happy Yom Kippur.” The week following April 1, please don’t offer us any baked goods.

Yes, you will have to look up these dates every year as well. But we’ll appreciate the effort so much more than in December.

It couldn’t be; the story of Hanukkah took place around 2,200 years ago, but the Torah is at least 2,400 years old.

Those would be Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, and Passover, not necessarily in that order but with Passover definitely in third.

Herein lies the alleged miracle: A reserve of lamp oil lasted longer than a group of besieged and sleep-deprived soldiers thought it would.

To be sure I wasn’t forgetting something, I checked out a few “top Hanukkah movies” lists, and Good Housekeeping and IMDb were both so shortchanged by terrible, generic rom-coms that they resorted to including Fiddler on the Roof and An American Pickle, neither of which depict Hanukkah at all!

Before that activity became the self-imposed duty of 4chan.

Per A Kosher Christmas by Joshua Plaut, the Rabbi of Metropolitan Synagogue in Manhattan.

Strict Kashrut rules would also prohibit the meat at Chinese food restaurants, since the animals usually wouldn’t have been killed in a Kosher way. But many American Jews keep some variation of “Kosher style,” meaning we’re strict on the type of animal consumed but not the method of preparation.

Rosh Hashanah technically starts the evening of Sept. 11, 2026, but, um, well, we’ll forgive you if you’re not really feeling the New Year’s Spirit that particular day.

Thanks for the piece. But re the hypothetical called-out comment that begins “Christmas is the most important Christian holiday…” I would say that’s borderline blasphemous for Christians for whom the Easter holiday and story are much more important to their faith (if not to the time, energy, and money they put into celebrating it!).

Hanukkah is shallow? What are you smoking? “Not exactly fuel for spiritual ponderance” - are you seriously going to argue that the question of countercultural religious distinctiveness is not relevant today? I don’t know what flavor of Judaism you subscribe to, but I can’t think of one that, on the one hand, takes seriously the question of whether Hanukkah shows up in the Torah to determine its importance, and on the other hand, doesn’t believe that the battle against Greek politico-cultural hegemony isn’t resonant with diaspora Judaism’s biggest challenges in the modern world, nor that the re-establishment of Jewish sovereignty wasn’t - and/or isn’t - religiously significant. I genuinely don’t know what you’re talking about in this whole section.

“The big tell here is that in Israel, one of the few places in the Western world where Christmas is not pervasive, Hanukkah is much less of a focus….” This is simply false. I just got back from a week in Israel; to say that Hanukkah was pervasive everywhere I went - from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv to Modiin to a kibbutz in the Beit She’an valley - is an understatement. Kids get off from school for the week, public menorahs are everywhere, Hanukkah-themed cultural events are the order of the day, etc. Maybe this is true in the specific sense of “less of a focus relative to Yom Kippur” - but there is no question that Hanukkah is more prominent in Israel than it is in the US, or that the median Jew in Israel does more to “observe” Hanukkah than the median Jew in America.

“Eight repetitive nights” - I literally don’t know anyone who does this. I have never heard of anyone who does 8 days of presents. If the claim is “well only a few of the nights are interesting” - last I checked Christmas is one specific day.

I’m going to stop doing the point-by-point critique here. This is just bad. It is depressing that this is building up to a case for “Jewish Christmas”. (I am baffled that we earlier made the case that Hanukkah is spiritually shallow to justify joining in with Christmas, a holiday now so utterly devoid of content that it’s plausible to write the phrase “Jewish Christmas” in 2025!) Hanukkah is quite flexible. It’s hard to imagine how someone can fail to concoct a version that works for them. If you can’t - no problem! It’s a free country, and as a card carrying Liberal, I am more than happy to give you “permission” to celebrate Christmas along with everyone else. But you don’t need to write this uncompelling, forced #slatepitch to justify it.

I will end my complaint on a conciliatory note: the conclusion is correct. The stuff that matters to Jews and Judaism is Rosh Hashannah, Yom Kippur, and Passover, far more than Hanukkah. If your appetite for observance is scarce, especially when it’s countercultural, your life will be richer if you devote your energy to those holidays. And it’s good to inform non-Jews about what the priorities are.