Education isn't a zero-sum game

The strange equity crusade against algebra

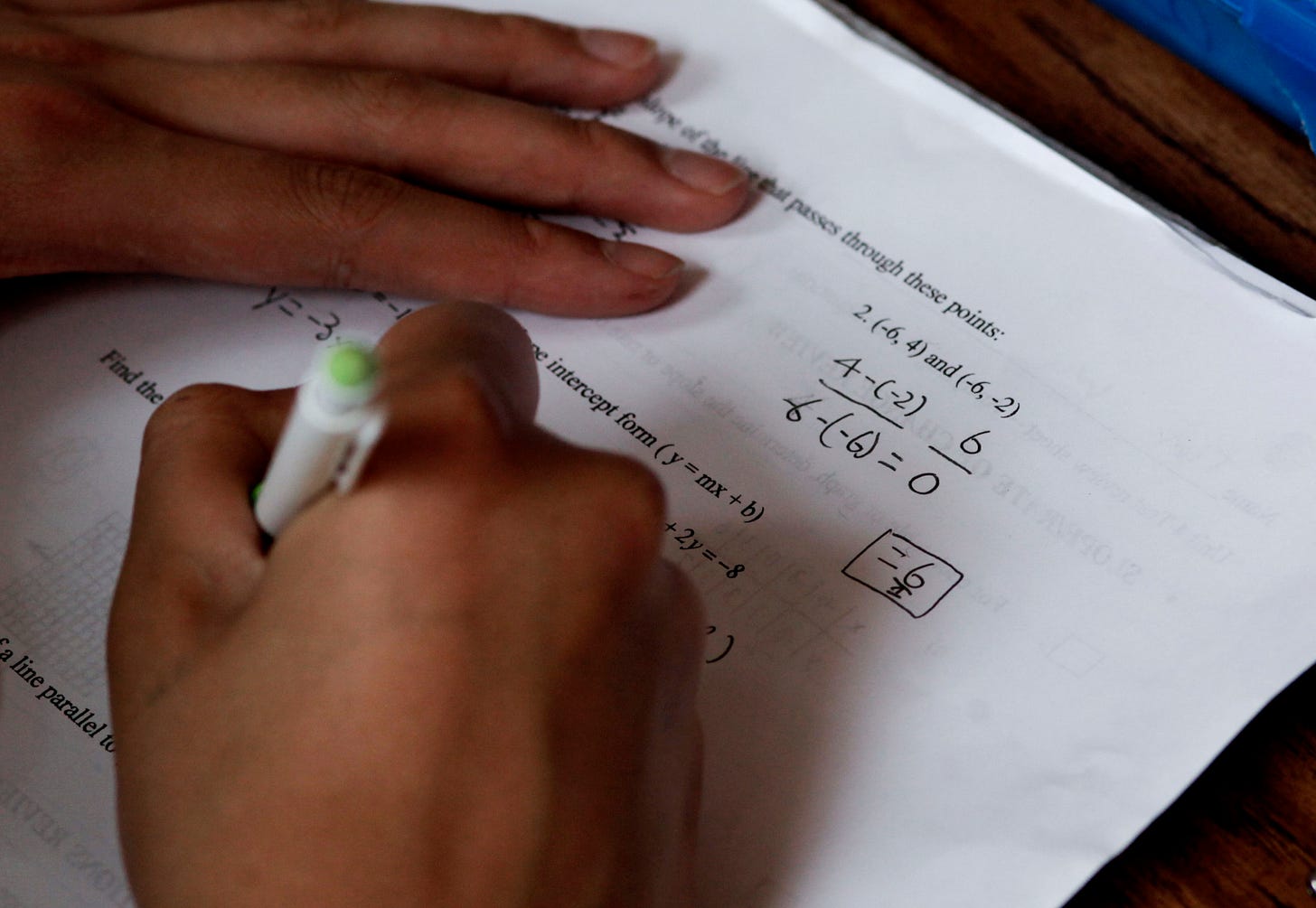

In 2014, too many kids were failing eighth-grade algebra, so San Francisco got rid of it.

This was part of a broader movement called “detracking,” an initiative advocated by the National Council of Supervisors of Mathematics (NCSM) and others in the world of math education. This would lead schools to stop offering advanced or remedial classes in favor of placing all students, regardless of ability, in the same classes. Tracking “too often leads to segregation, dead-end pathways, and low quality experiences, and disproportionately has a negative impact on minority and low-socioeconomic students,” the NCSM warned.

So San Francisco took the plunge. No students would take algebra in eighth grade. The hope was that the step would address the city’s glaring inequities regarding which students were high performers in math.

“We decided to detrack both out of the best academic interests of the students and out of a moral imperative,” San Francisco math teacher Kentaro Iwasaki told me. “Tracking mirrors the segregation in our society, maintains the haves and the have-nots. The segregation within our schools — if we walk down a hallway and we see a high-track class, it’s generally white and Asian students, and low-track classes generally Black and brown students.” Iwasaki had taught math at Mission High School in San Francisco prior to the detracking initiative.

The hope of detracking was that these disparities were being caused, in part, by a school system that read too much into children’s current performance, sorted kids into “gifted” and “not gifted” at too young an age, and put inappropriate academic pressure on top performers while treating weaker students like nothing much should be expected of them. The hope was that if schools treated everyone the same, the kids we had written off would rise to meet higher expectations.

“People have a ready-at-hand view that you’re trying to condemn slow kids to mediocrity and fast kids to being an isolated superclass,” Thomas Briggs, a researcher at the Center for Educational Progress, explained.

But detracking didn’t work. Some people like to muddy the waters on this, so I’m going to be exhaustive: The share of Black and Hispanic students scoring “proficient” in math didn’t budge.1 The racial gap in student enrollment in AP classes didn’t budge. In the first year of the program, Black enrollment in AP math actually declined because overall enrollment in AP math declined.

Over time, as the high school scrambled to restore pathways for students to take calculus, AP participation rebounded to its old levels. But “the percent of Black students enrolling in any AP math course has remained statistically significantly indistinguishable from the pre-policy period.” Student achievement didn’t improve in absolute terms or in relative terms.

The district pointed to signs of “success” — for instance, when Algebra 1 was offered in eighth grade, 40% of students repeated it, and now only 8% did. However, it obscured the fact that the district had eliminated the end-of-year exam, which many students tended to fail. More importantly, it obscured the fact that, on every objective measure of math knowledge, the kids were not doing better.

Detracking, like so many cheap attempts to end racism with one cool trick, does not help disadvantaged students reach their potential. It just makes it harder for any kids to do so.

Top colleges expect students to have taken calculus. Without it, students have an extraordinary difficulty pursuing STEM degrees. It’s possible to take algebra freshman year and complete calculus by senior year by doubling up on math or taking summer school, but San Francisco’s policies systematically denied a cohort of young people the chance to advance without extraordinary efforts.

Not only does removing opportunities for smart kids hurt those kids, it hurts the school system as a whole. Even parents who may agree that tracking creates disparities are rarely willing to offer up their children as social battering rams. If wealthy parents don’t believe schools are delivering their kids a good education, they will simply send their kids to private school.

To many parents, detracking became synonymous with destroying schools: “A lowest-common-denominator approach repels parents, and ultimately it weakens public schools,” Virginia education policy expert Andy Rotherham told me. “Parents are not going to put up with it. Parents who have the option to opt out will.”2

Maybe angering parents and forcing kids to take summer school would be worth it if detracking were delivering on its core promise — opening advanced coursework to more disadvantaged students. “If de-tracking was truly the antidote that it was claimed to be, I presume someone would be able to point to a district that de-tracked, point to their standardized test scores, and shout this success from the rooftops,” activist Alex Karpowitsch wrote me when I asked to talk for this piece. “I’m not seeing much out there.”

As I researched this piece, speaking with activists, educators, and policy wonks, I searched in vain for what Karpowitsch was asking for. I didn’t find it.

Does tracking work?

Before San Francisco embraced delaying algebra until ninth grade, the fad in education policy was the opposite: getting all students to take algebra in eighth grade for equity. But research from other districts found that while this helped — or at least didn’t hurt — high-performing students, it was “unambiguously harmful to the lowest performers.”