How do we live with each other?

What liberalism means to me

Almost exactly 70 years ago, in the first issue of a very different magazine — National Review — founder William F. Buckley proffered his classic definition of conservatism: It “stands athwart history, yelling Stop.”

This is the most memorable line from Buckley's publisher's statement. But the whole piece, as well as the following page listing the magazine's "convictions," is mostly a catalog of things Buckley, et al. opposed, like "growth of government" and "communism."1 The magazine went on to help fuse conservatism into a movement largely by defining conservatives as what they were not: namely, liberals.

Obsessed with blocking change? Overwhelmed and anxious at the rapid cultural, technological and political changes sweeping the nation? For years, I've criticized liberals for opposing growth, from new housing in their neighborhoods to new people in their cities. But revisiting how academics and thought leaders criticized (or sometimes praised) the conservative movement of the late 20th century for becoming defined by what it was not … it feels those criticisms could easily now be shifted against their former opponents. How seamlessly liberals have slotted into the place of the once-conservative institutionalists!

Some of us aren't even aware enough to be embarrassed by it:

In a recent 5,000-word article in the journal Democracy — one thing that hasn't changed about liberals is that we're simply never beating the wordcel allegations2 — William A. Galston, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, had a less catchy but uncomfortably familiar definition of modern liberalism: "The defenders of liberal democracy are the true conservatives of our time, seeking to preserve what is good about the present as the best basis for future improvements.”

Sorry to this William, but if this is the best pitch that liberalism can come up with, it will not only die, it will deserve to.

To transform liberals into mere defenders of the status quo is not just wrongheaded — it's wrong.

American independence was declared in the name of liberal principles. Those same beliefs inspired revolutionaries and reformers around the world, and at home. Liberal economics built modern industrial prosperity and developed social safety nets to provide for those who could not provide for themselves.

Liberalism is why we have Social Security, clean water and workplace safety regulations. And liberal principles are what made us the only nation in the world to define ourselves by what we believe in, instead of just where we come from.

The Argument was created to reimagine liberalism for the 21st century, but it was not created to endlessly lecture about political philosophy and the global world order. The battle for America will not be won through historical analogies and 5,000-word journal articles from tenured academics. It will be won if we can convince people that the issues they care about are best addressed through liberalism.

In the 2024 election, the American people demanded lower prices. What is postliberalism giving us? Tariffs, gutted biomedical innovation and a mind-boggling hostility to new forms of energy in the face of rising electricity prices.

In the 2024 election, the American people demanded an end to immigration chaos. What is postliberalism giving us? Chaotic deportations that fail to distinguish violent criminals from beloved neighbors, ripping American families apart.

If I'm forced to name a silver lining, it’s that liberalism is countercultural again. Donald Trump and the populist, postliberal Right are in power. An illiberal hostility to basic liberties and a cynicism toward progress flourish, albeit in a less coordinated fashion, on the left — this is the moment to strike back.

The tragic, iron law of our species is that human beings living together will differ in ways that they are willing to die over; differ in ways that they are willing to kill over. If you’re lucky, the worst you’ll ever feel toward another person is irritation or annoyance. But for most of us — particularly those of us with siblings — at some point we’ll feel what can only be described as murderous rage.

Liberalism sprang out of the unavoidable truth that there will always be reasonable (and unreasonable) disagreement, and that a world where people cannot live among those with whom they disagree is a world of chaos and endless cycles of retribution.

At root, it’s a philosophy that exists to answer one question: How do we live with each other?

Over the course of working on this essay, the president of the United States has deployed federal law enforcement to march down the street where I walk my dog; a handful of large corporations are running full steam ahead to create a technology that no one really understands, let alone knows how to control; untold thousands of civilians have been murdered in Gaza; and the United States has implemented a nonsensical tariff policy whose magnitude was last matched by the tariffs preceding the Great Depression.

This is nothing compared to what we have survived. Western liberalism largely emerged from the battle-ravaged aftermath of the Protestant Reformation. Europe had torn itself apart in religious wars that claimed millions of lives (exact numbers are evading the crack historical team here at The Argument, but anywhere from 4 and 8 million seem to have died in the Thirty Years War alone).3 One boy, born in the middle of the deadly Thirty Years’ War, looked on in horror as he grew up in England. Nearly three decades after the Peace of Westphalia, John Locke published his treatise on toleration:

"It is not the diversity of opinions (which cannot be avoided), but the refusal of toleration to those that are of different opinions (which might have been granted), that has produced all the bustles and wars that have been in the Christian world upon account of religion," Locke argued.

Three hundred years later, another philosopher was witnessing the aftermath of yet another war that had ravaged the European continent. Judith Shklar, who would escape both Hitler's Germany and Stalin's USSR offered one of my favorite contemporary definitions of liberalism: “The original and only defensible meaning of liberalism [is that] every adult should be able to make as many effective decisions without fear or favor about as many aspects of his or her life as is compatible with the like freedom of every other adult.”

Shklar’s definition is more complicated than it may seem at first glance. (Among the questions it raises for the philosophy heads: What counts as an “effective” decision? And how do we resolve that pesky compatibility issue?) But its core point is simple: The basis of liberalism is liberty. At The Argument, we believe in core freedoms to marry who you love, to read what you choose and to speak your mind.

But liberalism is not only about protecting people from state oppression. Unlike libertarianism, it also aims to build a government that enables individuals to live as they choose. After all, how can an adult make effective decisions without fear or favor if they have been denied an education? If they have no access to transportation between home and school? If they fear assault when they go grocery shopping? If companies exploit them at work? As University of Chicago philosopher Martha Nussbaum has written: “When comparing societies and assessing them for their basic decency or justice, [the question] is, ‘What is each person able to do and to be?’”

We are not agnostic between all possible lives — our commitment to individual liberties is not an excuse to wash our hands of judgment or devolve into moral relativism. There are better and worse kinds of lives, better and worse ways to conduct ourselves, better and worse decisions.

But how do we answer that original question? How do we live with each other?

Well, the ascendant answer to this question is simple: We can't.

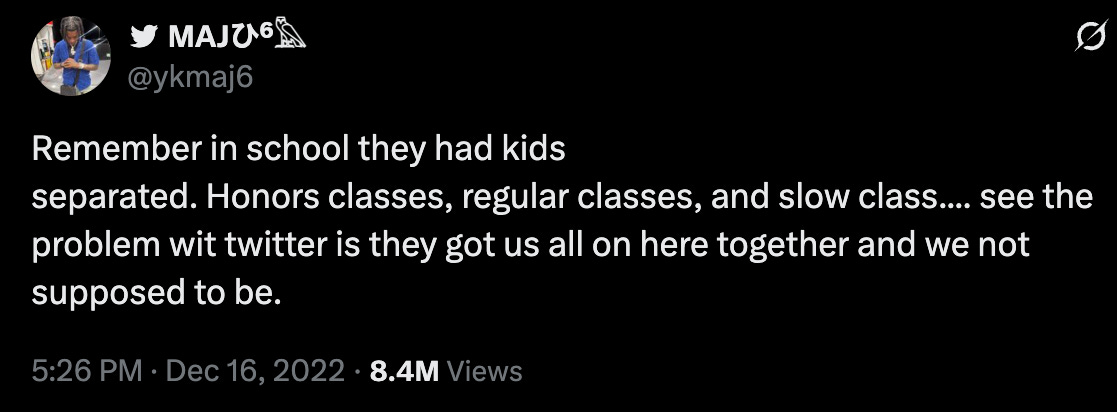

Sometimes, this answer comes in the form of a joke:

More seriously, the belief that America is simply too diverse for all of us to live together is migrating from the subtext of fringe political theorists to the openly expressed views of the increasingly powerful postliberal right. While Trump himself mostly leads from instinct, figures like Vice President JD Vance, White House Deputy Chief of Staff Stephen Miller and political theorist Patrick Deneen are carefully charting a new vision of America — or rather, a very old vision. Invoking anodyne institutions like "community," "culture" and "family," the postliberal right argues not just that these institutions are good (which most everyone agrees with) but also that individuals must be subordinate to them.

They further believe such subordination is natural: that we are intrinsically bound to the communities, cultures and families we were raised in, even against our will. They even believe that such subordination is good! That we are better off not even attempting to forge a new identity that might reject all or part of existing institutions. It is no accident that obsession with IQ, heredity, race and gender essentialism is all rising at the same time as anti-liberalism. It would be a mistake to view these trends as a “RETVRN to bigotry” — it is more than that: It is the return of an old, tired and powerful argument that people are nothing more than where they came from; that they can be held to account for the average properties of the groups that they belong to.

The key to understanding this crew is that they believe people have too much power. Power to say no to hierarchies, power to choose unconventional paths, power to be different. And so the postliberal right wants to make it harder to divorce, shows open contempt for those who decide not to have children and is dead set on redefining what it means to be American in blood-and-soil terms.

I'm largely focusing on the postliberal right for a couple of reasons. First, they are currently in power and represent the greater threat to humanity; second, they are more coherently organized. This is not to let the postliberal left off the hook at all. Much of my writing at The Atlantic and Vox has been critical of the rising anti-growth, anti-individualist parts of liberalism and the left. Whether it comes from obsession with tariffs; a suspicious love of localism, minoritarianism and decentralization; antipathy toward open debate and empiricism; poorly reasoned anti-immigration attitudes or just plain NIMBYism, postliberal ideas have sprouted up from the furthest-left corners of the internet to the center-left pages of The New York Times.

To many, postliberalism offers a compelling argument: “Look at all the division around us,” they say. “Wouldn't it be easier, wouldn't it be simpler, if we could just be less divided? If people in our communities largely shared our common heritage? If more people made the same choices that you do?”

This is, of course, a bunch of horseshit.

For all their obsession with Western culture and history, it often feels like none of the postliberal right have done the reading.

Remember Locke's reaction to the European Wars of Religion? He was writing about the largely white, largely Christian, largely immobile countries of Europe and even then he was seized by the truth that diversity of opinions could not be avoided.

He was right. The citizens of ethnically homogenous countries will find ways to divide themselves up over religion. Countries with religious homogeneity will find themselves divided up over caste. Countries with both will find ideological disagreements worth killing over.

This is the central folly of the postliberals: They cannot accept that at our core, human beings are individuals and, reasonably or not, we will seek to distinguish ourselves. During the Rwandan genocide, it is estimated that nearly 90% of the population was Christian; that homogeneity did not save them. Nor did the Greeks’ shared history, common ancestries, common religion and ethnicity save them from thousands of years of civil war. Ireland, East Timor, England, Sri Lanka … How many countries must face the same fate over and over before this ridiculous view can finally be put to rest?

Well, once more unto the breach, I guess.

So, how do we live with each other? There's not actually an easy answer. To live in a society, where some people think your way of life is unholy while you think theirs is immoral, is hard. Anyone who tells you differently is lying.

To answer this question is the work of this magazine.

Join us.

While building The Argument I went back to read many of the first issues of prominent American political magazines (yes, yes, I know) I'll probably do some more on this but it's fascinating to see how writers described themselves and their work at the outset. In particular, I loved The New Republic's first issue.

Buckley's column was just over 1,000 words. If you imagine me reading this at my usual 1.8 talking speed, mine is just a bit longer.

Yes, it has been pointed out that I am in fact lecturing you about political philosophy. I guess it's unavoidable.

first essay I’ve seen this year that isn’t afraid of the m dash

Great essay, great vision. I'm very excited to see where this goes!