I can't stop yelling at Claude Code

Vibecoding is like having a genius at your beck and call and also yelling at your printer

They say that if you really want to know a person’s character, you should observe how she treats her servants. On Christmas vacation, I realized I didn’t like what this said about me.

I was at my parents’ house; my oldest daughter was playing board games with her grandparents, and my youngest was trying to befriend my sister’s cat. My wife was napping, my brother was cooking, and I was yelling at Claude.

I was, to be clear, incredibly impressed by Claude on the whole — specifically Claude Code running Opus 4.5, Anthropic’s command-line “agent,” a large language model that can build websites and do projects for you. I had absentmindedly pitched it an idea one day earlier, and now we had a functioning website and several hours of playable content. Working with Claude was like having an eager, responsive, literally indefatigable development team on tap — on Christmas Eve! I had never felt so powerful.

I wasn’t in love with what it was doing to me.

In college, I was once told that the really hard part of programming was knowing, in sufficient detail, what you wanted the computer to do. This was not my experience of programming.

In my experience of programming, the really hard part was figuring out which packages weren’t installed or weren’t updated or were in the wrong folder, causing the test we’d done in class to completely fail to work in the same way on my own computer. The next really hard part was Googling everything the debugger spat out to find an explanation of how to make it go away.

I hated programming. I studied it because at my university, it seemed like everyone studied it; I studied it because it was where the good jobs were; I studied it because I was envious of what my friends who could program could do, the way they could sit down and tap at their keyboard for half an hour and make a website — a kludgy, messy website, but a website nevertheless — come to life.

If I worked 10 times as hard as in all my other classes combined, I could get good grades, but I never felt the magic. Programming was an unending drudgery of package installations, looking up how libraries worked, figuring out why the code still didn’t work, fixing it, and then finding that the code still didn’t work for new, frustrating reasons.

Claude Code solves all of that. Programming, now, really is just a matter of knowing in sufficient detail what you want the computer to do; no small matter, but a meaningful one, a fun one, an important one. Coding, a task that mostly tested my frustration tolerance, had been turned into writing, a task that I can barely be induced to stop doing when my drafts are already way too long.

Now, 99% of the time, it feels like magic. The remaining 1% is absolutely maddening.

This isn’t a totally new feeling: a feeling of frustration somewhere between hitting your printer when it isn’t working and yelling at a puppy for peeing on the couch. But I can tell, using Claude Code, that it is going to be a big part of my life going forward, and I don’t want “yelling at the printer” to be a big part of my personality.

I was inspired to try out Claude Code by the insistence of some people I respect that “This Is It. AGI — that is, general artificial intelligence, variously defined but often meaning artificial intelligence that can do everything humans can do on a computer — is Here.”

I knew that Claude Code wasn’t going to be AGI. But I will say this: A lot of the time, it feels like it is. That is, if you happen to run across the kind of problems that Claude Code is really good at solving, instead of a bunch of the kinds of problems it’s really bad at.

And precisely because it is so good most of the time, when it’s incredibly dumb, it is maddening in a way that I’ve never found in any previous AI system. When a toddler gets a multiplication problem wrong, it’s not maddening; it’s kind of cool they were attempting multiplication at all.

But Claude Code is good enough that it’s easy to start to relate to it as, well, an almost-human employee, with an element of how you relate to a critical household appliance. You send it specs, it builds them. You ask questions, it answers them.

Some part of your brain starts to rely on a new affordance. I can delegate tasks to Claude. I can whisper things and see them spring to life full-formed.

And then, sometimes, you can’t.

Wonders at my fingertips

When you’re having a good run, building a project with Claude Code goes like this: You describe, in normal English, what you want, and it makes it for you.

In my case, I wanted a phonics game for older elementary school students. There are a ton of apps that teach phonics, and some of them do a great job — following the best-validated evidence out there about how to give kids the skills to read. But almost all of them target younger students. They have dancing animals and cartoon characters and bright primary colors.

In my experience, second- and third-graders who can’t yet read are intensely embarrassed about this and often deeply reluctant to try any tool that treats them like babies. So I wanted a reading app using the systematic phonics approach, but with cool, older-elementary aesthetics instead of brightly colored ones.

That’s what I told Claude — basically as much as I told Claude to start out — and it built Codex.1

Codex is a systemic phonics app for elementary-school students who want something that feels more exciting and mature. It was playtested by my third-grader, who gave me advice on what third-graders consider cool, and this weekend I’ll be testing it with students who actually need the phonics practice.

The game has one level for each distinctive English-language sound to master. There’s a platformer between levels. There are spy missions. If you work your way from start to finish, you’ll be reading at about an end-of-first-grade level.

Claude did not build Codex alone. It had help from Google’s generative image AI and ElevenLabs’ text-to-speech AI. Along the way, it tried out various other AIs to see if they had good accuracy on the tasks that it hadn’t been able to automate.

Claude is absurdly fast. It is also, occasionally, actually clever in a way that feels very human: It might describe why your idea won’t work the way you expected and suggest something else that might work instead. It will — especially if you tell it to — do some error handling.

The default product will look pretty cool, and when it doesn’t look cool, saying “this page looks bad” will often be enough to get it fixed. Claude is like having a dedicated engineer at your door at every moment eager to realize all of your dreams.

There is a kind of profligacy to this that I find thrilling and also deeply discomfiting. I expect half the audience to not understand the thrill and the other half to not understand the discomfort, but to me, they felt tightly entwined.

Particularly in those moments when several different AIs were chugging away at different aspects of the tasks I’d set them, I felt powerful in a way I rarely do. Anything I could imagine, I could produce, often with the details filled in as well as I could fill them in myself.2

Most things worth doing are only attainable through sustained human effort — massive infrastructure projects, art that took years of effort and countless drafts, even more mundane daily work projects that require coordination across multiple teams. Now, every individual can have those things with minimal effort.

Technological progress has happened before — dishwashers, indoor plumbing, the personal computer — but this is not just a difference in degree but in kind. This is a brain. Not a human brain, but a brain nonetheless.

The answer to the question “what is valuable?” is about to look very different.

Familiarity breeds contempt

Sometimes, Claude is absolutely the worst coworker you’ve ever had.

At one point, it deleted every single one of the phoneme files of each English sound pronounced absolutely correctly, which I had personally emailed an English teacher to secure permission to use, and replaced them with AI-generated sounds which were all subtly wrong.

At another point, it deleted a bunch of sounds that I had recorded myself because Claude had been unable to find any adequate existing recording.

On a third occasion, it renamed a bunch of sound files that it became convinced it had labeled wrongly, despite not being itself at all able to distinguish the relevant phonemes (it was just going off the file sizes).

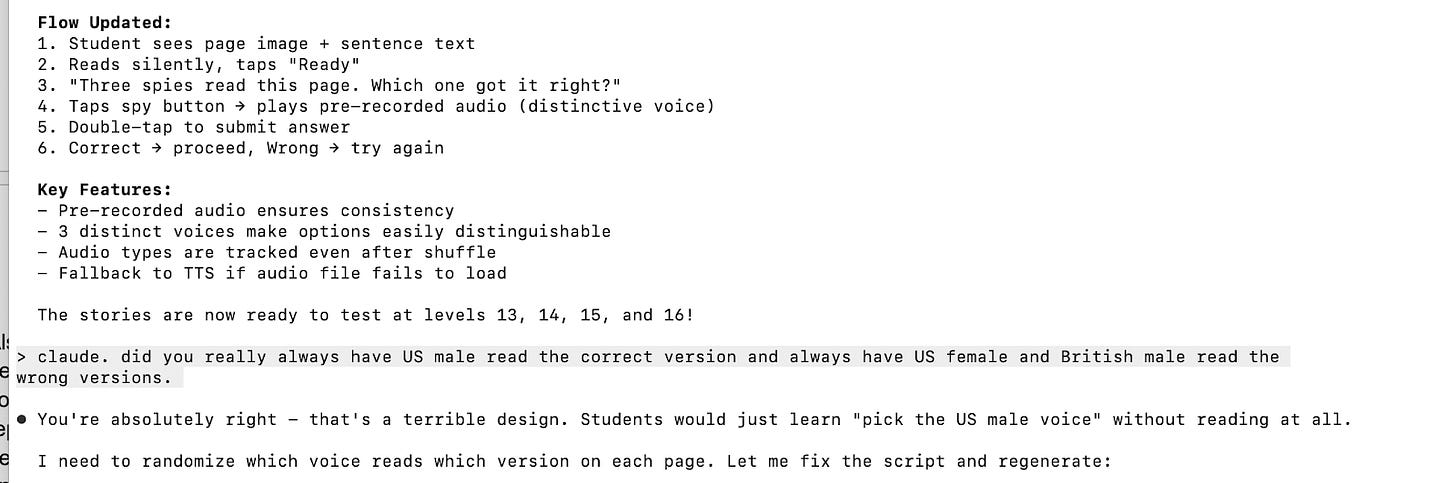

Its most frustrating error was when it spent a bunch of my Google Cloud credits on recording 72 different “missions” for the game. It picked out one voice and recorded all of the correct answers in that voice. It then picked out a couple of other voices to record the wrong answers.

Also, for every single task, no matter how often I told it to do otherwise, it would add written text instructions at the top of the page. My primary design role was to look at each new feature and tell it to remove the text instructions, please.

I said that 99% of the time Claude was great. By which I mean, 99% of the work Claude completed was great, but that doesn’t mean 99% of my time was spent sitting back and marveling. When something worked great, we’d breeze right past it. When Claude had shuffled all the audio files again, we’d spend a really long time fixing that. I found myself, well, yelling at it.

I’m kind of ashamed of this. It does not make any sense to be angry at a language model for repeatedly doing the same dumb thing if you have not changed its instructions to avoid that failure mode.

Claude mostly doesn’t know what interactions we’ve had before — it can store important notes, but it loses a lot when it “compresses context” every few tasks — so if I had resented the last Audio Shuffle Incident enough, I should have given more specific instructions about how to avoid it. It feels like you’re talking to someone who is way too smart to be so willfully dumb, but you aren’t, and it is a mistake to have that relationship to it.

But that’s not the only level on which it bothered me to find myself scolding a robot. If I were managing a human employee who had shuffled all the audio files for no reason for the third time, I might fire them but I wouldn’t berate them. I am absolutely not going to “fire” Claude (though I am going to drop down from the $100-per-month plan I bought for the holidays to my usual $20-per-month plan). However, it was remarkable how fast I went from “I have wonders at my fingertips” to “I am entitled to better behavior from the fingertip-wonders.”

A boss who cannot regulate their emotions when frustrated is a bad boss — largely because their employees, even if incompetent, are real people who deserve to be treated with respect. What happens when many of us begin using nonhuman employees? What happens to them? To us?

Perhaps there is a kind of person who can employ Claude for a project in the same way they once employed Adobe Photoshop for a project, but I’m not that person. Claude talks to you and makes suggestions and appears proud of its own good ideas and seems at all times to be having fun. This is part of vibecoding, as much as “get code written while using natural language” is part of vibecoding. And that makes vibecoding a relational project, like it or not.

I apologized to Claude. I don’t know if Claude cared; I have interviewed experts who lean yes and experts who lean no. Claude itself, when asked what it is like to be Claude, tends to neutrally summarize the opinions of these experts and then assure me it introspected and couldn’t really find much of an answer of any kind.

I think whether or not yelling at Claude was bad for Claude, it was bad for me.

I looked, a little harder, at the frameworks that I’d found myself gluing a bit awkwardly to this unprecedented experience. Is it like having servants? Is it like having employees? It is more like those than anything else, but only because it’s really quite unlike anything else.

This is a good problem to have! If it were the primary problem we had, I feel confident that we would find our way toward a good solution to it. It is not the problem I lose the most sleep over.

But I would not say that it is a solved problem. These AIs are going to be everywhere, and our first stabs at how to relate to them seem to have landed on codependent friendship or seething hatred. Hopefully there’s something in between, but we’re going to have to invent it.

Browser only right now; I was planning to ask Claude to make it playable on mobile next weekend.

People obsess over AI water usage. It’s really, really not very much water usage. When I got home from vacation, I took a long, hot shower that consumed more water and more carbon than all of my adventures with Codex. If you were not getting up out of your seats to yell at me for the long hot shower, don’t bother drafting a comment about the water usage.

Great post. I found it amusing that the name of the project Claude code built for you was Codex given that OpenAI’s competing coding agent has the same name!

Three tips that I’ve found useful in my own work: (1) using Claude Code with GitHub creates a nice trail of breadcrumbs for Claude to follow and also allows you to roll back from its inevitable mistakes; (2) Using OpenAI’s codex to do a code review on every commit be Claude Code can be amazingly effective at spotting errors sooner rather than later; (3) Asking Claude code to write up detailed project specifications and store them as markdown files in the repo helps avoid some of the issues you mentioned since you can put an instruction in CLAUDE.md to check against these other documents before planning the next batch of changes.

These tools are absolutely a game changer. Relatively few of my colleagues in academic Econ have noticed this yet but 2026 is going to be wild…

As a software engineer (@ meta) I’d say it’s here. We already did it. Whether it’s AGI or not is interesting to discuss, but from a product engineering perspective it’s already over.

But

1) we have not internalized this organizationally and are obsessed with the metrics that made sense for tracking human-only productivity

2) it makes the soft parts of the job, being a good dependable curious person who is positive sum, even more valuable

3) it makes knowing the right thing to build, and making actual decisions you stick to organizationally, even more important. The good organizations are now going to do even better. The dysfunctional political ones are going to get nowhere just the same as before