Is Mississippi cooking the books?

No. The skeptics are wrong. The Southern Surge is real.

The most important story in K-12 education is that a handful of states — and not the ones most expect — have figured out the tricky business of teaching kids to read. Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama have each bucked national trends by using a common approach and, in so doing, they have revealed the literacy playbook for even cash-strapped states in the Deep South. No excuses, California.

That story was everywhere last week, thanks to Kelsey Piper’s article here at The Argument, “Illiteracy is a policy choice.” In it, she took the media and elected officials to task for underplaying the trend. But the tide is swiftly turning: Last week, The Boston Globe declared that “New England Schools Are Failing” and that “the ‘Southern Surge’ should be a wake-up call.” The same day, Rahm Emanuel called for an “education reset,” saying these Southern state reforms should become “the meat and potatoes of Democrats’ education agenda.”

But not everyone sees these trends in the data as a path forward for pushing schools to take reading seriously. Freddie deBoer, the left leaning author of The Cult of Smart: How Our Broken Education System Perpetuates Social Injustice, published a fervent critique of Kelsey’s piece on his Substack. He closed with a challenge. “We’ll see if The Argument, a magazine seemingly founded on the premise that liberal good vibes can overcome every inconvenient fact and complication, will engage with this kind of criticism.”

Challenge accepted.

I — Karen Vaites — have spent years in the weeds of K-12 education reform efforts. I followed the success of the Southern Surge states as an independent education advocate, often focusing on the very technical details of their pedagogical choices. So I can say with some authority that in this case, deBoer is the one ignoring inconvenient facts and complications.

DeBoer accuses Kelsey of being “dismissive of all complication,” then proceeds to straw-man her points beyond recognition. Kelsey marvels at how four states with similar reforms yielded improvements in fourth-grade reading outcomes. DeBoer ignores the trend and talks solely about one state, Mississippi.

He characterizes Mississippi’s gains as “a sudden massive turnaround in outcomes,” even though Mississippi’s statewide reforms are at least 12 years old, dating back to 2013 legislation, and arguably two decades old, if you include pilot efforts spawned in 2000. Mississippi’s steady upward march on the National Assessment of Educational Progress — aka “the nation’s report card” — has been visible for a decade.

DeBoer characterizes the reforms in Mississippi as “minor administrative and pedagogical changes,” but spends zero time on what even happened in the state. The words “reading”1 and “phonics” are absent from his piece.

Instead, deBoer argues that Mississippi’s gains must be fakery because past education success stories have proven too good to be true. He points to the “Texas Miracle,” when officials under then-governor George W. Bush claimed testing and graduation rate gains. In reality, students were being reclassified in ways like being moved into GED programs, which hid dropouts from school rosters and manipulated outcomes. Pretty gross stuff — also pretty different from elementary reading.

As the most-liked comment on deBoer’s post put it:

“These are little kids. They are not dropping out to get GEDs at eight … They are, however, hopefully getting enough reading skills to meaningfully participate in society.”

DeBoer, done issuing challenges to this magazine, had no time to answer his own readers, it seems.

DeBoer’s long-running skepticism is well-founded; he cites multiple instances when Pollyannaish reformers have been fooled by — quite literally — incredible results. From programs that never worked as well as advertised to pilot programs that seemed to work great but fell apart when scaled, the education policy landscape is littered with disappointments.

But for deBoer, it seems like skepticism is not a rebuttable presumption but an article of faith. He doesn’t identify a specific problem with Mississippi; he just asserts that there has to be one. But he’s not the only doubter, so we looked into it.

Is Mississippi fooling us all?

Other naysayers have offered more specific grounds on which to dismiss Mississippi — but they generally have not held up. The state’s celebrated gains are on the federally administered NAEP assessment, which is notoriously tough to “game.”2

No, Mississippi’s retention policy isn’t altering the cohort of students being assessed. Investigations into Mississippi’s gains have concluded that “the state’s educational improvement appears to be legitimate and meaningful,” and researchers are consistent on this point.

One popular critique is that Mississippi’s third-grade retention policy — that students who can’t read at the end of third grade don’t go on to fourth grade — is artificially raising its scores by ensuring kids are older when they take the test. But this cannot account for the past decade of steady improvement; during that decade, the share of Mississippi students held back has not risen. The average age of students taking the NAEP hasn’t changed.

Another popular critique is that the gains in fourth-grade reading disappear by eighth grade. Since Mississippi has been gradually improving and introducing new reforms, we would expect lagging gains in eighth grade anyway, but here’s a different angle: In 2013, Mississippi eighth graders had an average reading score 15 points lower than the national average. In 2024, they were five points below the national average — and 25th-percentile readers in Mississippi had drawn even with 25th-percentile readers nationally.

The truth, of course, is that both the critique and the counter are true, and each in isolation is misleading. Mississippi has closed the gap with the nation — but only because scores fell everywhere else, especially during COVID-19, and Mississippi held steady. Not a miracle, but still a sign of something going right.

The most likely way Mississippi could be fooling us — as deBoer points out — is through selection bias like “widespread underreporting of dropouts, ‘disappeared’ struggling students, and data manipulation.” Kelsey looked into whether Mississippi could be selectively excluding students from the NAEP.

Spoiler alert: Almost certainly not.

Mississippi had fewer kids excluded from taking NAEP due to a reported disability (1.31% of students) or lack of English proficiency (0% of students) than most states in 2022. The national average was 1.55% of students excluded due to a disability and 0.78% excluded due to English proficiency.

What about if you just look at all Mississippi students missing the test for any reason? Mississippi had a weighted student response rate of 92.7% in 2022 — above the national average of 91.6%.3

Yet, for the sake of thoroughness, the data on disabled students and Mississippi does contain one red flag skeptics could pounce on — though Kelsey found it herself and hasn’t actually seen anyone point it out. In 2013 when Mississippi first began adopting its policy changes, the state was an outlier in rarely identifying students as disabled. Mississippi only identified 10% of students as having a disability, and only 6% of students received accommodations.

That was well below the national average. High-performing Massachusetts, by comparison, identified 19% of students as disabled in 2013, and 15% of its students got accommodations. Mississippi probably didn’t have fewer disabled students than other states, but it seems they were less likely to systematically screen for disability.

Then, starting in 2017, as part of reading reforms, Mississippi mandated screening for dyslexia. The share of students identified as disabled rose; the share receiving accommodations on the NAEP rose to 8% in 2017, to 9% in 2019, and to 11% in 2022.

In other words, Mississippi used to wildly underidentify its share of students with disabilities, and Mississippi students were much less likely than students nationally to receive accommodations. Today, Mississippi students are about as likely as students elsewhere to receive accommodations. They are also slightly more likely than a decade ago to not take the test at all — in 2013, only 0.5% of students did not do so, wildly below the national average of 2.14%. Mississippi is still below the national average, but not by as large a margin.

At least some of Mississippi’s perpetual 50th-place performance was the fact that it classified so few of its students as disabled, and we readily acknowledge that this shift could be driving some of its recent gains.

If the Mississippi miracle were just more kids getting accommodations on testing, then our initial reporting would have badly missed the boat. It would still be a good thing if more disabled kids were getting the help they need — but it would suggest very different takeaways than the ones we have written about. “States that are probably wildly underestimating their disabled student population should screen for disability” is good policy, but it’s not a reading revolution.

To check whether we’re looking at “Mississippi caught up to all other states in its ability to identify disabled students” or “Mississippi improved reading instruction for all students” we would want to check whether nondisabled students are improving or whether most of the gains are from the students who are now getting accommodations. Luckily, the NAEP reports percentiles. We can pull Mississippi’s data and find that student reading scores are increasing in every percentile listed since 2013: the 10th percentile went from 161 to 170, the 25th from 186 to 196, the 50th from 211 to 222, the 75th from 234 to 245, and the 90th from 253 to 262.

What does all this mean? It means that Mississippi’s improvements since 2013 are extremely unlikely to be just a consequence of more special-ed students receiving accommodations. That might have dragged them out of 50th place but not all the way to ninth — not even close.

This is a very different pattern than what we saw in Texas, where reclassification of students and gaming of score cutoffs enabled a higher pass rate. The top decile’s performance in that case was totally flat.

Still not sold? Kelsey spent the whole day in NAEP crosstabs, looking for any comparison group under which the Mississippi gains disappear. Here’s an argument that might be more persuasive to deBoer, who argued in The Cult of Smart that in terms of societal effects on economic growth, “The data shows that what really matters is the academic performance of the top 5 percent of students”:

In 2013, only 3% of Mississippi’s fourth-grade public school students earned the highest score on the NAEP reading test. That has now more than doubled to 7%. Dropping or somehow hiding low-scoring students would never achieve that result.

Mississippi’s weakest students are doing better, and so are Mississippi’s strongest students.4 There is a sizable and sustained improvement here, which is not a consequence of selection or accommodations, and which is the policy outcome of interest to us. Not all averages are created equal: Medians are more robust to chicanery than means. Excluding a lot of students from the test might do it, but that’s about it — and Mississippi is excluding fewer students than most comparison states.

The defense rests.

Basically all kids can learn to read. Here’s how.

No one claims that Mississippi eliminated its achievement gaps — or solved all its educational or social problems. But it’s an absurd leap from “we don’t know how to close achievement gaps” to “we don’t know how to equip students with any skills at all.”

In general, better instruction doesn’t seem to close achievement gaps — even with an incredible teacher and a great curriculum, weaker students are still relatively weaker and the stronger students still relatively stronger. But all of them learn more — and that’s still a win.

The benefits of literacy are not positional, they are absolute. It is good that children can read because it equips them to navigate our world, even if some of them can parse Tolstoy while others tap out at The Hunger Games.5

Even after all this work, there’s plenty that isn’t fixed. But we’re not claiming a handful of states revolutionized education — just that children can be taught to read even if it doesn’t fix everything else. If two states in the country with among the highest rates of childhood poverty — Mississippi and Louisiana — have increased the share of public schoolchildren who can capably read in fourth grade, so too can other states.

This is not a story that poses a threat to leftist ideals; the fact that through sustained investment in high standards for public schools, we can better equip our poorest and most disadvantaged students with the life skills they need the most is great news.

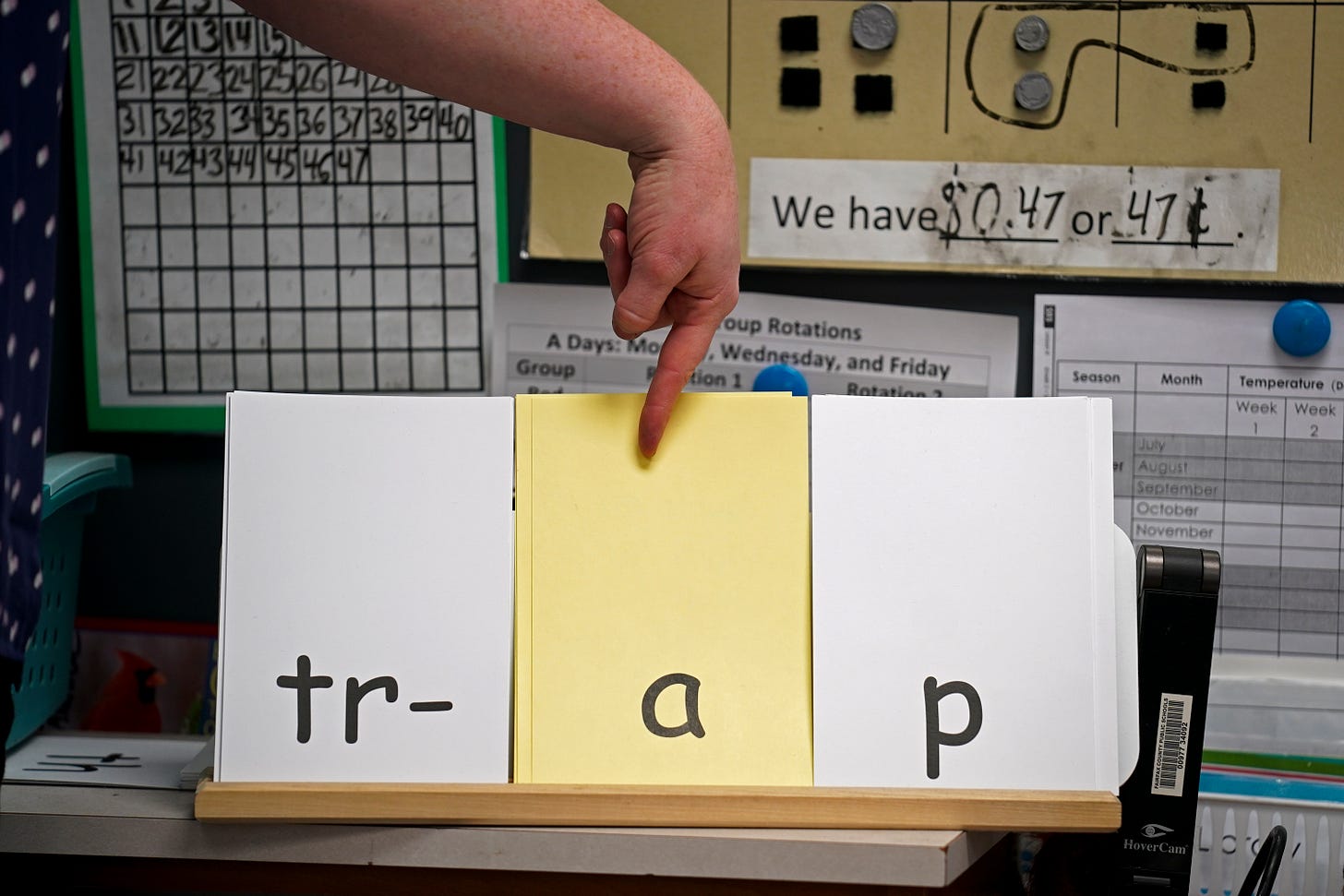

First, we must get straight on the plays in the Southern Surge playbook. Because, for the love of God, it’s not just phonics. There are four parts to the playbook:

Mandatory screening of students in grades K-3, three times a year, using approved assessment tools, to monitor how early reading skills are developing

Focused efforts to improve curriculum quality in schools — for phonics and other aspects of literacy

Large-scale efforts to train teachers

Retention policies to hold back students who aren’t reading successfully by the end of third grade

Many focus on the retention policies. They are important and do seem to motivate adults to pull out all the stops. But kids cannot learn to read on retention mandates alone. Retention policies work because so much is done between Kindergarten and third grade to ensure all kids develop reading skills.

Before a student is retained, he or she will be screened 12 times across four grades, using a quality screening tool approved by the state. Well-trained teachers will have quality lesson materials, and they will know which students need extra support. It’s a system set up to work so that very few students need to be retained in third grade — which is exactly what happens.

One can debate the best order of operations.6 But one cannot reduce those multilayered reforms, which have been underway for 20+ years in Mississippi, 13 years in Louisiana, six years in Tennessee, and six years in Alabama, to “they just went back to basics with phonics.”

There weren’t simply ”some pedagogical tweaks,” as deBoer quips. It would indeed be implausible for some tweaks to get results like these. Mississippi’s results set off many people’s bullshit detectors because they believe (rightly) that no small change would change things that much. But what they are missing is that the changes are not small — and they have tailwinds.

The Common Core standards spawned innovation in knowledge-building curriculum a decade ago. Today, schools can choose from vastly better options than in previous eras. This “curriculum renaissance” was critical for Louisiana’s and Tennessee’s reforms.

In addition, strong journalism helped spark a grassroots literacy movement. Emily Hanford’s viral podcasts reached educators and parents alike. Motivated teachers and parents of children with dyslexia organized to reform state policies and succeeded. Forty-five states passed literacy legislation between 2019 and 2022, offering the clearest signal that literacy reforms can achieve widespread, bipartisan embrace.

The enabling conditions seem ripe and the playbook is clear, but many states are phoning it in. Whether due to a lack of political will or opposition from interest groups, half-baked measures masquerading as serious K-12 reform remain the norm. In California, the state teachers union succeeded in killing legislation in 2024 and watering down legislation this year. Massachusetts legislation hangs in the balance, amid opposition from the Massachusetts Teachers Association.

It’s even possible that the Southern Surge states take their foot off the gas. Alabama’s scores have yo-yoed over the last two decades, moving in lockstep with state policy shifts, and even Mississippi state reading results were modestly down in 2025.

There are other headwinds blowing dangerously on the horizon: declining school enrollment, chronic absenteeism, increased behavior issues since the pandemic, mission creep away from core academics … the list goes on and on.

Public pressure is the only way for these policies to prevail. Most states — red, blue, and purple — need to catch up with the pacesetters. The Southern Surge is happening in four states with Republican governors, though most of the work in Louisiana happened under Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards. A few blue states have shown creative flair, such as Massachusetts’ pointed incentives to get crummy curriculum out of schools.

The Southern Surge is consistent with both progressive and conservative goals: On the left, strengthening public institutions, and on the right, improving education. To embrace it, leaders will need to revisit stale thinking, like the insistence that increased spending is the only way to improve student outcomes. They will need to get unions onside. And they will need to tune out snarky columns by disaffected leftists dunking on Mississippi because it doesn’t fit their priors.

To be fair, the topper of deBoer’s article does mention the word reading, in relation to a book talk he is giving.

The Texas Miracle debacle noted by deBoer, and the Atlanta cheating scandal, actually illustrate the value of the NAEP assessment. Even as state exams showed large increases, Texas and Atlanta NAEP scores remained flat, which helped to illuminate the fishy state practices. The NAEP is harder to game because it selects different schools to evaluate each time — one school or cluster of schools cheating would produce a one-time spike, not the steady improvement we see.

Consider the magnitude of the effects we’re trying to explain with classification fudging. In California, only 28% of Black fourth graders read at or above basic level, for instance, compared to 52% in Mississippi. The rates of test noncompletion simply can’t explain the differentials in test performance.

Despite all of this, I was, in fact, myself unsure how seriously to take the results in Mississippi until I saw the positive results from the other states imitating it. Improvements are good, but often don’t scale. What makes Mississippi exciting is that, when we imitate the things they did elsewhere, we also see improvements. With the “Texas Miracle,” as deBoer notes, efforts to copy the winning formula didn’t work because there was no real winning formula to copy. But efforts to copy Mississippi appear to be working.

In his book The Cult of Smart, deBoer bemoans this exact conflation: “we say we care about absolute learning, but what we really care about is relative learning.” But here he engages in it — because he has decided relative learning gains are impossible, he adopts a posture of skepticism that Mississippi’s massive absolute-learning gains are similarly impossible.

The sequence varied. Mississippi and Alabama initially started with targeted teacher training on how kids learn to read plus retention policies. They sent state coaching teams into low-performing schools, and phased in curriculum improvements later. Louisiana and Tennessee started by improving curriculum statewide and training teachers on how to use the new curricula. Broader training on literacy fundamentals and third-grade retention mandates came later.

The oddest part of DeBoer's criticism of Kelsey's original piece is it's been DeBoer who has been consistent on the idea that absolute gains are possible with the right pedagogy, but that there's no way to reliably close achievement gaps (or that it's even a good policy metric to pursue). And he's right! I am not sure what got him so bothered about the Mississippi article. I saw his first commentary go something like "control f 'texas miracle', no results, ignore".

I think he literally might have scanned the article for the Texas Miracle, didn't find any mention of it, assumed the article was about achievement gaps, started ripping off a hot take, and then was in so deep he couldn't retreat. Just weird because he's completely correct that closing gaps are hard/maybe not worth doing but absolute performance can be enhanced with good methods.

Education policy is not something I know much about. Prior to Kelsey’s piece last week I didn’t know about what had happened in Mississippi but it certainly looks amazing and I hope other states copy it with similar results. What I don’t get is why teachers’ unions oppose it. I get why they fight all kinds of things that could force accountability for their members as much as I dislike that. I just don’t see how doing what Mississippi did threatens them. Can someone explain why they oppose it?