No country for young families

"Having a child is like having leprosy." The dark side of senior housing projects.

I don’t know for a fact that Franklin, Tennessee, is trying to keep poor kids out of their city, but it sure looks like they are. A dark secret of affordable housing development in the U.S. is that towns routinely discriminate against families with children by using homes for the elderly as a cover.

Here is an overview of Franklin’s completed affordable housing projects according to the Franklin Housing Authority:

Eight units of affordable housing for low-income renters

48 units of affordable housing for seniors

Six units of affordable housing for low-income renters

18 units of affordable housing for low-income renters

48 units of affordable housing for seniors

20 units of affordable housing for low-income renters

10 units of affordable housing for low-income renters

12 units of affordable housing for low-income renters

Now I’m no shape rotator math whiz, but I believe that comes out to 74 units for low-income renters of any age and 96 just for seniors. Also, the two senior housing projects simply dwarf the other affordable housing developments.

I first started paying attention to Franklin several years ago when I spoke with Kennetha, a homeless mom in Nashville, Tennessee. Kennetha dreamed of living in a nicer suburb but, as she told me then, “Franklin is meant for rich, white people.”

It’s well known among those who work on poverty issues that the greatest crisis is among the young — children had an official poverty rate of over 15% in 2023, significantly higher than working-age adults or seniors. And yet, when suburbs like Franklin go to build affordable housing, time and again they build housing that bars children and young people.

I first learned about this phenomenon from Connecticut fair-housing lawyer Anika Lemar. Denying people an apartment based on their family status has been banned nationwide since 1988. But when local governments build or authorize new below-market-rate homes, they routinely use a loophole in the law that allows them to restrict new housing to adults older than 55.

Lemar says that, as a rule, she now refuses to help suburbs build affordable housing for seniors, after seeing how communities in her state used it to block out families with kids.

“It wasn’t rocket science to know what was going on,” Lemar told me — just garden-variety discrimination. Even though housing discrimination against families with children is technically illegal, the practice is still common and infrequently punished. Elected officials and private citizens alike will readily admit to favoring senior housing precisely because children can’t live there.1

In a rare case over the issue, the Department of Justice filed suit against the city of Arlington, Texas, in 2022, alleging it had blocked an affordable housing development because it had a policy of only supporting developments funded with Low-Income Housing Tax Credits if they were restricted to people 55 and older.

According to the DOJ complaint, multiple municipal officials openly discussed their discriminatory intent. One council member described his constituency as virulently anti-child: “the community said ‘I don’t want to live next to a three-year-old; the only thing worse than living next to a three-year-old is living next to an eight-year-old,’ so they wanted senior housing.”

Kids are annoying. They’re loud. They’re destructive. They combine random cleaning chemicals on the ground during playtime (at least I did). They kick the walls. They have no sense of their impact on others. Kids are psychopaths. But kids are also people — people who need housing.

The type of discrimination I’m about to describe is insidious. There’s no smoking gun. There’s no evil NIMBY twirling his mustache. It’s an untraceable network of decisions, some overt, but mostly clandestine. Inequality multiplies, and yet somehow, no one is to blame.

Here’s what’s overt: On publicly viewable real estate boards, landlords and housing investors solicit and offer tips — in some cases using what appear to be real names — about how to scare off potential tenants with kids.

“Nothing stops you from giving creative directions to the place. While driving down Main Street, make a left a Wally’s Liquor [sic]. If you see Tiny Tim’s Titty Club you’ve gone too far,” a Los Angeles rental property investor suggested in one such thread.

A real estate broker in Wyoming offered a less-convoluted strategy for discrimination that reveals how quickly anti-kid discrimination becomes discrimination against the poor: “Poorly behaved children tend to belong to lower-class parents that shift jobs and locations often, have poor credit, low income, etc. By screening applications and selecting people with secure jobs, good income, and good credit, you will reduce the risk a ton.”2

Researchers began to notice rampant discrimination against families with children in the housing market in the 1970s. A pair of nationwide studies from University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research found that 26% of all rental units excluded families with children. And another 50% imposed restrictions such as limiting the number of kids, the age of the kids, or where in the building kids were permitted to live. One of the studies included a poll in which 49% of respondents with children in the household reported that the last time they’d searched for housing, “they found places where they wanted to live but were unable to because of policies about children.”

Studies of individual cities painted a dark and detailed landscape of discrimination. In Des Moines, Iowa, a survey of landlords found 48% of them did not permit children. Research in Alexandria, Virginia, revealed that only 9% of the city’s rental units accepted children without restrictions. Investigators in Florida’s Orange and Seminole counties discovered 36% of rental vacancies prohibited children.

And this was just the explicit discrimination. During 1987 hearings on whether to amend the Fair Housing Act to include discrimination against children, James B. Morales, then-staff attorney at the National Center for Youth Law, explained to Congress: “Even when a landlord does not adopt an overt no-children policy, he or she may as a matter of practice consistently select childless households over families with children.”

Families at the receiving end of this behavior weren’t stupid. Diana Pearce, director of WOW’s Women and Poverty Project, also testified in the 1987 hearings, recalling as one parent put it that “having a child is like having leprosy.”

Pearce told Congress that in order to find housing, families were routinely splitting up temporarily, for up to four months, as they searched for somewhere that would allow parents and their children shelter together. Nearly a quarter of all renters with children reported settling for a less-desirable location according to the U-M findings.

Moved by the damning testimony of various experts, Congress amended the Fair Housing Act in 1988. Until that point, it had prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, and sex; now, familial status and disability would be added to those protected categories.

A little over a decade later, a review of the effectiveness of these (and other) changes made in 1988 found that from 1989-97, familial status complaints were the most likely to lead to charges, more than twice as likely as race-based or disability-based complaints.3

Yet before the 10 years were even up, despite — or rather because — of this progress, Congress rammed a cement truck-sized loophole into the Fair Housing Act.

The cement truck’s formal name is the Housing for Older Persons Act, or HOPA, and it passed overwhelmingly in the Senate on Dec. 6, 1995. The measure made it much easier for an apartment building to qualify as senior housing, even if the majority of residents were not seniors and there were no facilities or services tailored to the elderly.

The Congressional Record indicates that animus toward children was a significant motivation behind the bill. As Sen. Hank Brown, R-Colo., put it: “The fact is, some older people do prefer not to have the noise and trauma that go along with having children [around].”

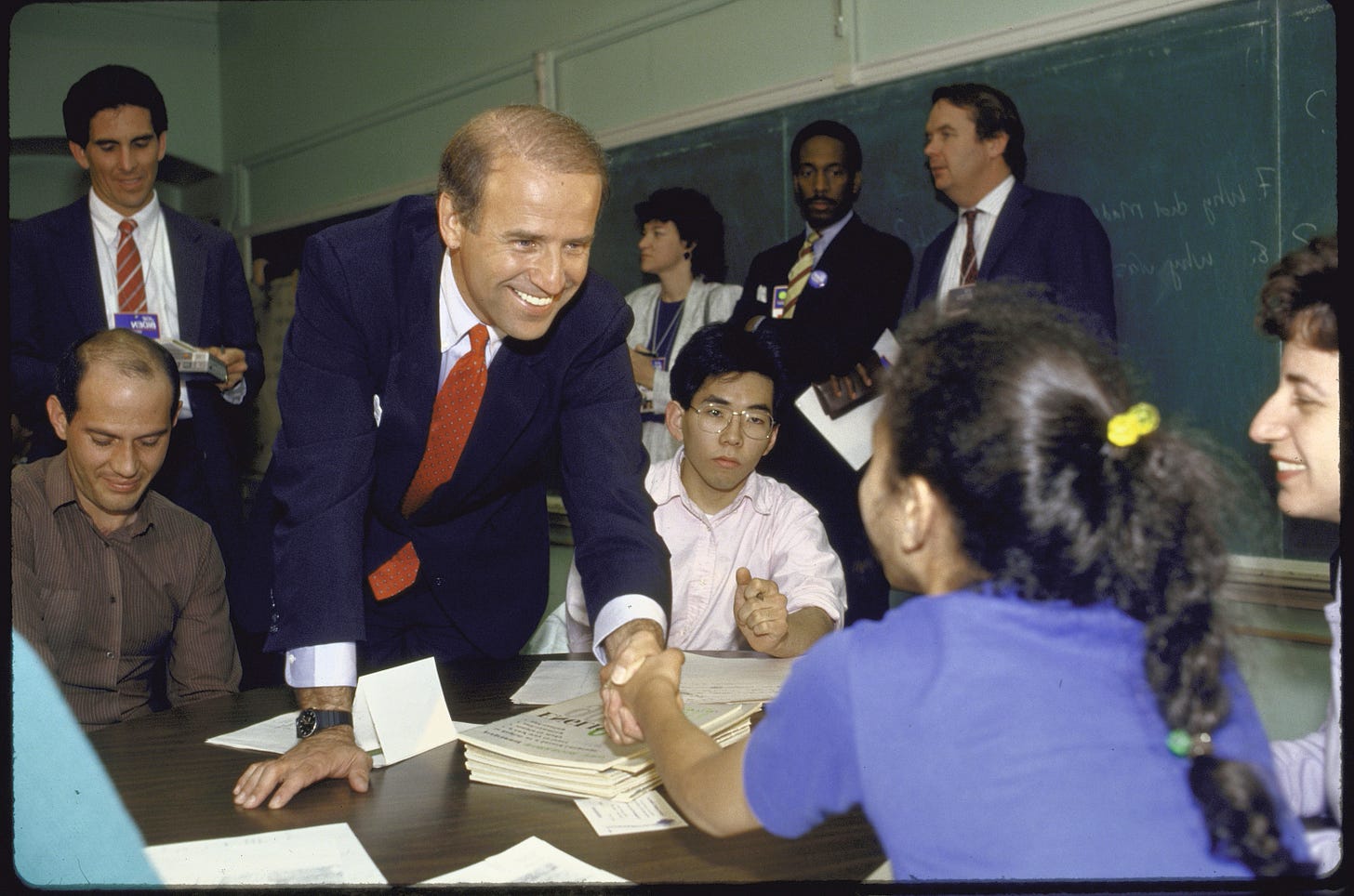

Just three members of the U.S. Senate voted against the bill: Lincoln John Chafee, R-R.I.; Patrick Leahy, D-Vt.; and most notably, Joseph R. Biden, D-Del.

Biden — who had previously been a single father — clearly saw what was happening. Under the guise of promoting housing for seniors and under pressure from exclusionary towns and the senior lobby, Congress was granting a license to discriminate against children and families.4

“The bill’s supporters say [it] will make it easier and surer for a housing community to determine whether it qualifies for a fair housing exemption, and they are absolutely right about that,” he said in a floor speech. “It makes it a lot easier. They do not have to be a senior facility. They can just not like kids. They can just not like kids around.”

He was right. Today, communities across the country “have weaponized [HOPA] to shield themselves from liability for obstructing affordable housing, perpetuating residential segregation, and denying housing to low-income families with children,” Rubin Danberg Biggs and Patrick Holland wrote in the Yale Law Journal.

Lemar’s rule is fundamentally a reaction to another unwritten maxim followed by many local governments — particularly nice, suburban ones that have perfected the art of exclusion: Don’t build affordable housing, but if you have to, no kids allowed.

It’s difficult to find any hard numbers quantifying how often families run up against age-restricted housing in the present day. And yet, throughout my years of reporting on housing issues, affordable housing developers have regularly volunteered to me how commonplace anti-kid discrimination was.

“I can’t tell you how many community meetings I’ve been in where we’re proposing family housing and then someone says, ‘Well if you made it senior housing, we could support it,’” Rebecca Mautner, vice president at a Massachusetts-based affordable housing developer, told me last year. “I mean it’s very direct.”

Even if they witness this sort of obvious discrimination, developers are unlikely to report on it, or even fight it strongly if it risks their future projects. Firms work with the same towns, zoning boards, and gadflies year in and out, and local officials can sandbag or kill a proposal in any number of ways. Better to stay quiet, get some affordable housing than none, the logic goes.

The result? Developers tailor their projects to avoid as much backlash as possible, and work with towns to get to the most acceptable project, even going so far as to abandon project ideas entirely if it feels like an uphill battle. If they choose to fight, they’re in for a pyrrhic victory — the complicated nature of layering different financing tools to build affordable housing means that long delays can kill a project’s viability a hundred different ways.

Sunshine Mathon, an affordable housing developer who has worked in both Texas and Virginia, tells me that, “there’s an unspoken truism that if you’re doing a senior housing project, that the tenants will be less problematic, and that the affordable housing community will have less ‘negative impacts’ within the neighborhood … if you’re going to pitch a senior project, in those kinds of neighborhoods you’ll have minimized or reduced opposition.”

One of the more remarkable aspects of pitting senior housing against housing for low-income families is that it’s not clear most seniors actually want it. Rodney Harrell, an AARP vice president who leads the organization’s team of issue experts, pointed me to research he has done showing that only 26% of people 50 and older want to go to a 55-plus community, while the overwhelming majority seek to stay in their own home and community as long as possible. AARP has slowly become a leading voice in pushing for broader liberalization of the housing market, on the theory that if enough housing is built in all communities, seniors, like everyone else, will have more options.

Clark Ziegler, the executive director of the Massachusetts Housing Partnership, tells me that in his state, senior housing projects may have even been overbuilt, pointing me to a report from the Citizens’ Housing and Planning Association, an affordable housing nonprofit in Massachusetts. The report looked at age-restricted active adult housing, which it defines as "developments that offer individual units for sale or, less frequently, for rent to financially secure, healthy adults aged 55 or over” and found that development growth was "being driven by local land use policies and fiscal considerations.”

That’s a nice way of saying, “Exclusionary policies and old people don’t require more spending on public schools.”

At the time, the report determined that there has been a wellspring of age-restricted housing developments while those for younger housing has stalled. It documents 70 communities with zoning provisions that support the production of senior housing.

The bias toward providing age-restricted housing appeared to be creating a supply glut, the report found. The result of this likely wouldn’t be a bunch of empty units, but rather a drop in prices, inducing more seniors to choose age-restricted housing developments who otherwise would have preferred to remain in mixed-age communities.

In short, many communities across the U.S. have adopted a form of legal housing discrimination that ensures cheap places to live for financially stable Gen Xers and Boomers, while leaving families with children nowhere to turn.

One weird trick

There is no “one weird trick to stamp out housing discrimination.” There are just too many people and decision-makers involved. But this isn’t an impossible problem: We need to enforce fair housing law — for starters, I shouldn’t be able to go online and find landlords sharing tips on how to discriminate. (To any pro-natalists in the executive branch reading this, it would be great if you could own the libs by going after exclusionary Democratic suburbs that discriminate against families with children.)

Second, I think the biggest lesson from the YIMBY movement so far is that the persuasion campaign is as, if not more, important than the legal changes activists have demanded. Making the argument for more housing is not about pointing at lines on a supply/demand graph, it’s about developing the constituency and arguments for why new housing is good.

David Broockman, Chris Elmendorf, and Josh Kalla wrote a paper called “The Symbolic Politics of Housing,” in which they show that people’s reactions to certain “symbols” like “developer,” “tall building,” or “cities” can explain when residents oppose new housing construction.

People don’t become NIMBYs just because they’re obsessing over their property values, they become NIMBYs because — at some point — they learned that new housing or new luxury housing or housing built by developers was bad. Similarly, many people have learned that affordable housing, living near children, and in particular living near poor, Black children is bad.

This is not the sort of thing that a transit-oriented development bill can fix. We need a real persuasion campaign to show landlords, towns, and voters that affordable housing for families isn’t going to destroy their communities.

Just as civil rights activists strategically deployed Black families to calm fears about racially integrated neighborhoods, that kind of activism needs to be deployed again in defense of families with children. In Don’t Blame Us, historian Lily Geismer describes the 1962 “Good Neighbors for Fair Housing” campaign where activists asked some white suburban residents in Brookline, Massachusetts, to sign a pledge promising to “rent or sell the property he or she owns or manages without regard to race, religion or national origin and to encourage neighbors to join with them to achieve an integrated neighborhood.” Geismer points to contemporaneous editorials that noted the persuasive power of this campaign, which gained endorsements from local and federal elected officials.

Senior housing has become a “one weird trick” many towns and suburbs have seized on to keep kids (and poor families) out. Housing for retirees might be politically popular. But the law that created it has become a tool for abuse, and it has to go.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the first name of John Chafee, one of three senators who voted against HOPA.

Discrimination is difficult to root out, or even study, particularly in the private market. As a HUD study once noted about housing discrimination, “every routine act, every bit of ritual in the sale or rental of a dwelling unit can be performed in a way calculated to make it either difficult or impossible to consummate a deal.”

If a landlord declines to rent to families with children but never explains herself, if an apartment building markets itself to adults and property managers routinely miss appointments if someone shows up pregnant, if applications get denied without justification, who can say definitively what happened?

Some more gems:

A handyman named Jim in Pittsburgh recommended to describe the neighbors as crack addicts, “just ignore him when he asks if you’ve got ‘“leven dolluz’ to spare, he does that to every…um…well…oh yes! Every ethnic European person in the neighborhood.”

A rental property investor in Erie, Pennsylvania, received 15 upvotes for “the neighbors dogs love kids..yeah he has 5 pit bulls he lets roam unleashed. Don’t worry though ,he’ll be going to prison for a few years soon [sic]”

Chuy, an investor in Long Beach, California, recommended getting “kids with two married parents.”

At one point, Christopher, in Keene, New Hampshire, said folks should be “suuuuuper careful” with leading questions as they could be considered discriminatory. His comment received zero upvotes.

“Charges were issued in 619 cases, the majority of which involved claims based upon familial status, (61%) followed by race (16%) and disability (14%).”

The 1988 amendments already had a reasonable exception for senior housing, one which left enough room for entities seeking to build housing for seniors that actually served specific needs, but not enough room that people could simply exclude children and nominally claim an interest in housing seniors.

Heartbeat laws for room occupancy are also bad! I have three kids on one room (ages 5.5, 3.5, 1y) and it's going surprisingly well.

But if I were on Section 8 or under CPS attention, it would often be prohibited (and some local zoning codes prohibit it too). Let parents make reasonable tradeoffs + don't force us to rent/buy more home than we need or seek units the market isn't building!

Boomer here. Totally agree with all points. I set up a YIMBY table at our summer community markets (12 weeks) to talk to people about why housing at all income levels is good and developers are good. I am clear that I was anti-development in the 1970s and I was WRONG. I do lose my temper when people whine about parking and traffic. Are cars more important than people??

Regarding senior housing, I live in Santa Rosa and we have just closed all our middle schools and several elementary schools are on the list for closing due to lack of enrollment. Sonoma County is 29% seniors and we cannot sustain a school district because there are not enough kids. The short-term as well as long-term consequences are deep.

Meanwhile the guy who installed my internet commutes 1-1/2 hours from the east bay where he lives with his mom. That's 3 hours/day of unpaid time, cost of car, and air pollution. All because we don't have enough apartments for the people who work here.

"Affordable housing" means government-controlled tenancy, NOT "housing that I or someone I know could afford". I had an interesting discussion with another senior in the Kaiser waiting room last week. She is looking for a new place to live due to her small garden apartment being converted somehow. I suggested some of the "affordable" opportunities both senior and general public, and she said "they have too much control. I would have to re-certify my income every year." This from an elderly white woman, so you can imagine what younger women go through in affordable housing projects. I've advocated on behalf of women whose adult sons or boyfriends want to live with them in a deed-restricted apartment but who are not allowed to live with them due to history of incarceration or drug use.

We need abundant housing at all income levels to allow capitalism to work.