The anti-socialists who love to social engineer

Central planning, with helicopters

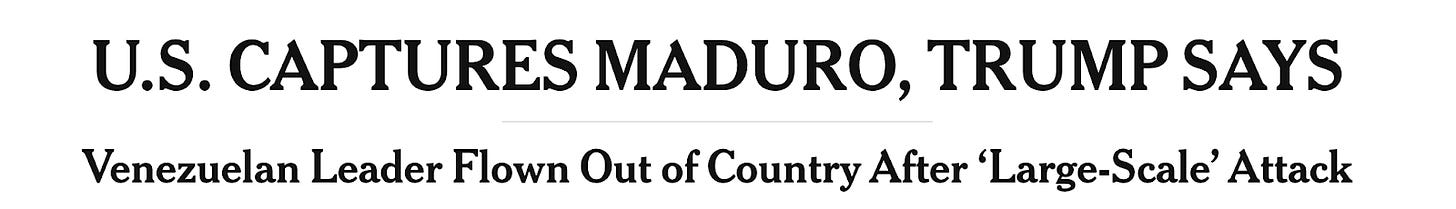

Saturday morning, the Western hemisphere woke up to an ALL CAPS headline from The New York Times.1

As most of you have probably heard, the Trump administration captured Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro Moros in the early hours of Saturday, Jan. 3. From a military perspective, this extraction was very different from when the Obama administration killed Osama Bin Laden in 2011. For one, unlike Pakistan, Venezuelan defenses were a very present risk — American forces flew helicopters into downtown Caracas and remained for almost two and a half hours.

According to Gen. Dan Caine, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, various aircraft were responsible for “dismantling and disabling the air defense systems in Venezuela,” which is a vaguely euphemistic way to explain the strikes that led to civilian deaths, according to a senior Venezuelan official.

The biggest question is, of course, what now? Many waited for President Trump’s Saturday morning address to the nation with bated breath — what brilliant plan would our commander in chief grace us with? Well, the details are sparse, but the pronouncements that shocked most of the country (and the world) were that the “people that are standing right behind me, we’re going to be running [Venezuela],” referring to Secretary of State Marco Rubio, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, and Caine. Trump added that “we’re not afraid of boots on the ground.”

Trump also denigrated the Nobel Peace Prize-winning opposition leader, María Corina Machado, and indicated that Maduro’s vice president was essentially a U.S. pawn.

No one is using the same democracy-spreading rhetoric that President George W. Bush used during the Iraq War; his administration argued in favor of a “democratic domino,” where a free and democratic Iraq would lead to the spread of democracy throughout the Middle East.

But in a conversation with The Atlantic’s Michael Scherer, Trump argued that “rebuilding there and regime change, anything you want to call it, is better than what you have right now. Can’t get any worse.”

Determined not to be misunderstood, he repeated himself: “Rebuilding is not a bad thing in Venezuela’s case ... The country’s gone to hell. It’s a failed country. It’s a totally failed country. It’s a country that’s a disaster in every way.”

Sunday evening, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board egged the president on, lamenting that the Trump administration might be willing to leave the Maduro regime in power: “But despite Mr. Trump’s vow that the U.S. will ‘run the country,’ there is no one on the ground to do so. This may mollify MAGA critics who fear he is imitating George W. Bush’s occupation of Iraq. But it reduces the U.S. ability to persuade the regime.”

In some ways, this all feels uncomfortably similar to the last Republican president’s experiments in the Middle East. Except, at least then, the people in charge seemed nominally reluctant to embark on a prolonged sojourn in Iraq. People forget, but the Bush administration had repeatedly held that “they did not believe that nation-building was the sort of operation in which the U.S. military should be involved.”

But, of course, we did end up attempting to nation-build in Iraq. And it’s very possible that we end up doing something of the sort in Venezuela too.

It’s worth thinking through why Republicans keep doing this. There’s an interesting tension between how many right-wing leaders talk about the failures of communism and socialism and their blind faith in the ability to centrally plan other nations from afar. Putting aside the obvious moral and democratic issues with trying to run another nation, there are just staggeringly obvious practical problems that, time and again, our right-wing leaders seem intent on ignoring. Why?

The knowledge problem comes to Caracas

Friedrich Hayek’s famous paper “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” laid out the core argument against central planning: The economic problem of society “is a problem of the utilization of knowledge not given to anyone in its totality.”

As Hayek pointed out, all economic activity is planning, and the question he is interested in is the debate between central planning or decentralized planning — through competition where many different people are in charge of many different plans. The way to decide which system is better is by evaluating which one can make better use of existing knowledge.

With prices, individuals who each have a very small portion of the total available knowledge can coordinate. Someone who finds a new, productive use for aluminum in South Africa will immediately begin buying a lot of it. Prices will rise, and no one has to know what that person has found or that she has found it; they simply react to the rising prices by consuming less aluminum.

The converse is a central planner who somehow has all the information in the world to determine the best use of each input, an especially daunting challenge in a world where change is a constant.

Hayek’s work has been foundational for critics of communism and central planning since it was released in 1945. Even Trump, who is no principled free-marketer, has been influenced by anti-central planning thought. In a 2019 speech to Miami’s Venezuelan-American community he argued:

“Not long ago, Venezuela was the wealthiest nation, by far, in South America. But years of socialist rule have brought this once-thriving nation to the brink of ruin. That’s where it is today.

“The tyrannical socialist government [of Venezuela] nationalized private industries and took over private businesses. They engaged in massive wealth confiscation, shut down free markets, suppressed free speech, and set up a relentless propaganda machine, rigged elections, used the government to persecute their political opponents, and destroyed the impartial rule of law.”

Rubio, who is widely acknowledged to be the driving force behind the administration’s focus on Venezuela, has repeatedly criticized Cuba and Venezuela for their centrally planned economies.

But in the realm of foreign policy, that Hayekian insight — that economies are too complex, that there is too much local knowledge dispersed across billions of actors, for any planner to successfully direct from above — disappears.

What explains the hubris of believing that price controls in your own country are a disaster in the making but that it’s possible to direct the politics of a foreign nation from afar? A nation with its own history, factions, ethnic tensions, and institutional legacies?

It may be, at least in part, that the Hayekian insight has been largely abandoned by the right, and while they may parrot some anti-planning talking points as mere echoes of an earlier time, they no longer really believe them. This is possible. But even avowed free-marketers within the Bush administration made the exact same mistake.

At core, though, I think Trump, Bush, and large parts of their respective administrations simply do not think that people in other countries are as complex or real as in their own. That simplistic belief that one could decapitate a dictator and remake the economy and politics implies that the dictator is the sole or even major cause of these problems rather than an equilibrium outcome of underlying forces that can reassert themselves.

With Iraq, there were widespread assumptions that basically all Iraqis would be ecstatic at their liberation, that Saddam Hussein’s regime was a balloon ready to pop, and that soldiers wouldn’t join an insurgency. In hindsight, people realized that despite the seeming weakness of the nation, the Ba’ath Party was actually growing stronger. Strategists who believed the Ba’athists to be weak counted on local leaders to continue governing themselves, instead a power vacuum opened up, encouraging competing factions to fight for control.

It’s completely reasonable that these outcomes were not well predicted. It’s very hard to perfectly model the politics of an entire nation, let alone to use that to predict the future. There are too many unknowns, too many pieces of knowledge dispersed among too many people.

We all understand this when it comes to our own countries but routinely act as if our simplistic models of other countries will hold true.

In 2019, the U.S. Army War College published a comprehensive retrospective on the Iraq War, which at one point concluded: “the most significant aspect of the Iraq invasion planning was not the shortage of troops or the lack of Phase IV planning, but rather the gaping holes in what the U.S. military knew about Iraq. This ignorance included Iraqi politics, society, and government—gaps that led the United States to make some deeply flawed assumptions about how the war was likely to unfold.”

I am not totally opposed to all military intervention.

For instance, I think a coalition intervention in Sudan right now would make a ton of sense, and, in hindsight, I think the same for Rwanda. In situations where the potential loss of life is overwhelming and extremely likely, the benefits of intervention can outweigh the costs.

But such situations should be undertaken with a coalition whenever possible, hopefully in partnership with groups within the nation itself, and the goals should be very targeted — like preventing immediate genocidal killings. Even these actions are likely to have unpredictable ramifications, but if the expected costs of doing nothing are extraordinarily high, the risk can be worth it.

Most importantly, though, this sort of action should be a last resort.

Reports indicated that pressure from the U.S. had begun to wear Maduro down but Trump was unwilling to accept a deal that left Maduro in power, even if the Venezuelan leader made other significant concessions. On a November 21st call between the two leaders, Maduro reportedly offered to leave Venezuela if he and his family were given full legal amnesty. An offer which Trump rejected.

Over the following several weeks, Maduro’s government indicated again that it was open to negotiating with the United States its stated concerns: Access to Venezuelan oil and combatting drug trafficking.

I’m not going to take Maduro’s word for it that he was negotiating in good faith, he doesn’t strike me as a very trustworthy guy. But, an objective read of the escalating violence doesn’t fill me with confidence that my government was negotiating in good faith either.

If the administration stops with Maduro’s capture and allows politics to play out in Venezuela without further intervention, it’s possible this will all end up for the best. Maduro was a vicious dictator who drove millions of people out of their own country, and no good future for Venezuela included his continued leadership.

But administrations are too often intoxicated by quick, successful, military victories. Such a small proportion of what a president does is as direct and satisfying as an effective military operation. Even Trump’s tariff policies, which have been largely unilateral, are far more indirect than ordering the capture of a foreign dictator.

Already, signs of inebriation are showing themselves. The charming announcement of a “Donroe Doctrine” implies a desire to impose the president’s will upon the entire Western Hemisphere.

The U.S. cannot govern Venezuela. We should probably try governing ourselves effectively first.

I do enjoy that there is clearly a decision point when news is breaking where senior Times editors get together and decide whether it merits an all-caps headline or not; there’s a good reported essay to be written about the stories that almost earned that honor. On the other hand, I do not enjoy that the Times has decided that its breaking news stories should be live blogs; hopefully now that no one cares about Google SEO anymore, that will go away. But I digress.

“I think Trump, Bush, and large parts of their respective administrations simply do not think that people in other countries are as complex or real as in their own. That simplistic belief that one could decapitate a dictator and remake the economy and politics implies that the dictator is the sole or even major cause of these problems rather than an equilibrium outcome of underlying forces that can reassert themselves.” Yes, this.

In addition to the obvious motivations--distraction from Epstein, oil, his love for strutting his dominance--with Trump you can never rule out petty jealousy, and Maduro actually succeeded in overturning an election he lost.