The loneliness crisis isn't just male

23,000 survey results are in.

Men are lonely. Maybe it's because they are marrying later and working harder. Maybe it's because “women are outpacing them in school and at work.” Maybe it’s because they don’t know how to text or because they don’t have old boys’ clubs anymore.

We’ve read all sorts of takes on mental health over the last several years, but few of them are substantiated by hard data. That’s why we at The Argument decided to conduct a study over the last few months centered around mental health.

Over the course of three national surveys of registered voters conducted between August and December, we asked 15 questions — five per survey — centered around loneliness, mental health, anxiety, and socialization. Each response was mapped to a numerical value between -1 and 1, with -1 indicating the most antisocial and 1 indicating the most social response.

With nearly 23,000 responses to survey questions distributed over more than 4,500 individual survey respondents, our dataset is rich and lends itself well to subgroup analysis.

Here’s what we found.

The loneliness crisis has been over-gendered

This is the traditional story about the male loneliness crisis: Millions of young men are increasingly antisocial, fueled by unique and accelerating feelings of loneliness and isolation, along with toxic podcasters in the manosphere. In the process, they’re finding it harder to make friends, harder to trust others, and harder to interact with the rest of society.

A lot of people meet this with denial. For example, a study from the Young Men Research Initiative analyzed the top Bluesky posts on male loneliness and found that a large chunk of them either denied that the problem existed, blamed men for it, or simply belittled the crisis as overblown.

But there is a loneliness crisis in America, and the evidence in support is increasingly undeniable. What our polling reveals, though, is that it’s a youth loneliness crisis, rather than a male loneliness crisis. Age, not gender, shows far greater correlation with antisocial attitudes and beliefs. Younger voters — both male and female — are increasingly paralyzed by anxiety and fear, and they are finding it harder and harder to socialize.

In fact, when you look at the data, the “antisocial crisis,” as I like to call it, is actually most pronounced among young women, who experience the highest rates of social isolation.

Put another way, it’s true that young men are facing a loneliness crisis. But it’s part of a broader loneliness crisis that young voters are facing in general, and the numbers suggest that young women might actually be hit even harder, even though that story hasn’t gotten nearly as much attention.

Let’s dive in further by looking at the results from our study on the questions concerning emotional distress. To measure this, we presented respondents with a set of statements and asked them to mark whether they agreed or disagreed with each one as a description of themselves1:

I get easily overwhelmed

I dislike myself

I panic easily

I have a difficult time starting tasks

I am a worrier

The gender split is striking, and it is robustly substantiated by the existing medical research. But it is age, rather than gender, which marks the determining axis once again. Just take a look at how bad these numbers are among young people — both young men and young women were significantly more distressed than the country at large.

For instance, young men (18 to 29) are more distressed than almost every other demographic, including women 45 to 64 and women over 65. But young women are hit even harder, and they actually have the worst scores among any age-based gender cohort in our entire dataset.

Anxiety and distress may not be the first topics that comes to mind when it comes to the loneliness crisis. But they happen to be deeply intertwined with healthy social interaction in many ways. That’s why I find it so significant that young people are far more anxious than the country at large. They are much more likely to suffer from panic, fear, self-loathing, and a lack of motivation — and young women, in particular, have some strikingly bad numbers here.

Let’s look at another axis of our study: social disengagement. This axis more directly concerns loneliness, with questions centered around friendships, social life, and conversational comfort. To measure this more directly, we presented respondents with a subset of the following statements,2 asking them to mark whether they agreed or disagreed with each one as an accurate characterization of themselves.

I prefer to be alone

I have a hard time making or keeping friends

I keep others at a distance

I feel that most people can’t be trusted

I find it difficult to approach others

I only feel comfortable with friends or family members

I frequently feel lonely

Once again, young people emerged as the age group most likely to feel lonely, isolated, or conversationally stunted with people they don’t know, and there is a striking gap between the “internet generations” (people under 45) and everyone else.

Here, the gender gap is significantly less pronounced, but it’s actually widest with young voters. While both young men and young women suffer from a loneliness and socialization crisis, young women actually seem to be hit significantly harder by it. In particular, they seem to find it much harder to make new friends or converse with strangers, especially when it comes to the opposite gender — and they’re much more likely to be introverted and alienated.

The results of our study lined up quite well with the existing research on this topic. A study conducted by Public Opinion Strategies found that young women are the cohort of Americans most likely to feel lonely and left out. And it doesn’t seem to be limited to just America — a study done by the United Kingdom’s Campaign to End Loneliness found that women and young people were two of the cohorts most affected by loneliness.

Our poll’s findings on young people being more antisocial are also substantiated by broader societal patterns observed over the last few decades. For instance, it’s well-documented that young people party less. That isn’t a bad thing, in and of itself, but it’s reflective of a broader and more worrying social trend, where young people are spending less and less time socializing with each other. (The American Time Use Survey estimated a nearly 50% decline in face-to-face interactions among teenagers over the last two decades.)

Time that used to be spent with friends is now spent online — a trend accelerated and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Perhaps relatedly, the prevalence of mental health disorders is on the rise, with young people being the most heavily impacted. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the internet generations are, by some distance, the most socially disengaged.)

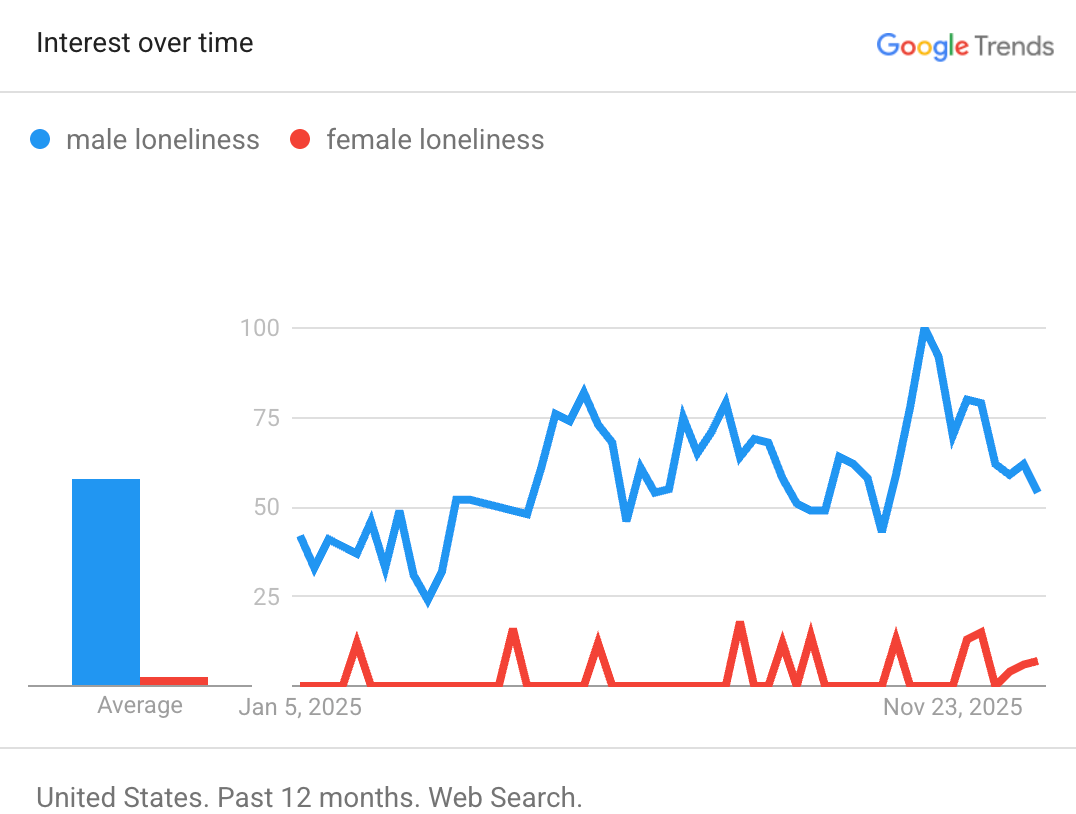

The evidence for a loneliness crisis in America is overwhelming, and it is worrying that so many people are in denial about this problem. As a matter of fact, when it comes to the “female loneliness crisis,” I’m not even convinced that most people know it exists. Just look at the Google Trends data on this.

You can find column after column on the male loneliness epidemic. But when it comes to the female loneliness epidemic? Crickets.

This is a real problem. The loneliness crisis isn’t manufactured, and it doesn’t spare either gender. Every data point we have suggests that a troubling proportion of our youth are anxious, antisocial, and lonely — and this problem appears to be getting worse, not better.

The consequences of ignoring this are real, as research has suggested loneliness and unemployment tend to reinforce each other in a feedback loop. And the collapsing birth rate problem certainly isn’t helped by young people becoming increasingly anxious and antisocial, especially with the opposite gender.

What’s the solution to the problem? I’m not sure. But the Discourse’s unrelenting focus on gendering the loneliness crisis is biasing us toward answers that are unlikely to be true. If young people as a class are suffering, the root cause is unlikely to be something that just affects one gender.

(Next week, for paying subscribers, we’ll be diving into what our loneliness study reveals about Democrats and Republicans. Are liberals really unhappier than conservatives? And are people who don’t care about politics really more well-adjusted than the MSNOW/Fox News crowd? Subscribe to find out!)

Methodology:

Over the course of three national surveys of registered voters, conducted between August and December, we asked 15 questions — five per survey — centered around loneliness, mental health, anxiety, and socialization. In total, we had 4,559 respondents, providing a total of 22,795 responses across all 15 questions.

The questions included in the study, as well as the subcategory they were mapped to, were partially sampled from a set of questions tested by Blue Rose research. The questions, along with the subcategory we grouped them into, are as follows:

I prefer to be alone (Social/Antisocial)

I have a hard time making or keeping friends (Social/Antisocial)

I keep others at a distance (Social/Antisocial)

I feel that most people can’t be trusted (Social/Antisocial)

I find it difficult to approach others (Social/Antisocial)

I only feel comfortable with friends or family members (Social/Antisocial)

I frequently feel lonely (Social/Antisocial)

I have a hard time befriending the opposite gender (Social/Antisocial)

I get easily overwhelmed (Anxious/Content)

I dislike myself (Anxious/Content)

I panic easily (Anxious/Content)

I have a difficult time starting tasks (Anxious/Content)

I am a worrier (Anxious/Content)

My daily life has been filled with things that interest me (Active/Inactive)

I have felt active and vigorous lately (Active/Inactive)

The available responses for these questions were: Strongly agree, somewhat agree, neither agree nor disagree, somewhat disagree, and strongly disagree.

Regarding our numerical coding process: For most items, “strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” were coded as antisocial. However, for the final two items — “My daily life has been filled with things that interest me” and “I have felt active and vigorous lately” — the coding was reversed, and “somewhat disagree” and “strongly disagree” were coded as antisocial.

For any given question, the “strongly” antisocial option received a value of -1.0 and the “somewhat” antisocial option received a value of -0.5. The “strongly” social option received a value of 1.0, and the “somewhat” social option received a value of 0.5.

“Neither agree nor disagree” was given a value of 0, as the neutral midpoint.

More polling:

Some of you are lying about reading

A few months ago, a 2021 Pew Research Center study on Americans and their reading habits caught my eye. In particular, this survey said something astounding about the number of Americans who read: Seventy-seven percent of Americans said they read a book (in whole or in part) over the preceding year in some shape or form

Have Democrats lost their education edge?

For the longest time, it was the Democrats who held a commanding edge on education. Even in the reddest of areas, with no Democratic Party, bench, or liberal culture to speak of, Democrats would pull scores of conservative voters for elections concerning

October respondents were presented with the statements “I have a difficult time starting tasks,” “I panic easily,” and “I dislike myself.” November respondents were presented with “I am a worrier” and “I get easily overwhelmed.”

October respondents were presented with the statements “I have a hard time making or keeping friends” and “I prefer to be alone.” November respondents were presented with “I keep others at a distance” and “I get easily overwhelmed.” December survey questions were ”I feel that most people can’t be trusted,” “I find it difficult to approach others,” “I only feel comfortable with friends or family members,” “I frequently feel lonely,” and “I have a hard time befriending the opposite gender.”

The emotional distress response rating prompts ("I panic easily") code as more feminine and I am not surprised men were less likely to respond yes. It's much more socially permissable for women to admit to things like panic than men. The social disengagement prompts ("I prefer to be alone") code as more masculine, so it's not surprising to see a reduction in the gender gap there.

Also I don't think this survey is getting at what most people consider the loneliness crisis. What this survey captures well is that mental health and self-reported mental wellbeing is correlated to age, with young people reporting higher negativity than older people.

When I think of the loneliness crisis however I think more of results/things you do in the world. Less a report of emotional status than "do you hang out with friends? How many do you have? How frequently do you socialize?", all of which I have seen convincing data showing men are more physically isolated.

To be fair, that's only descriptive, and this survey is more explanatory. Interesting stuff.

It's not that surprising that this has become framed as the male problem.

Men are more prone to react to emotional distress with externalising behaviour, so when men are lonely, they lash out and make it everyone else's problem.

Women, on the other hand, tend to react with internalising behaviour, which is much less visible to the outside observer, even though the distress might be just as severe.

It's telling that the term "incel" was coined by a woman, but made infamous by men.