The things you can't make people do

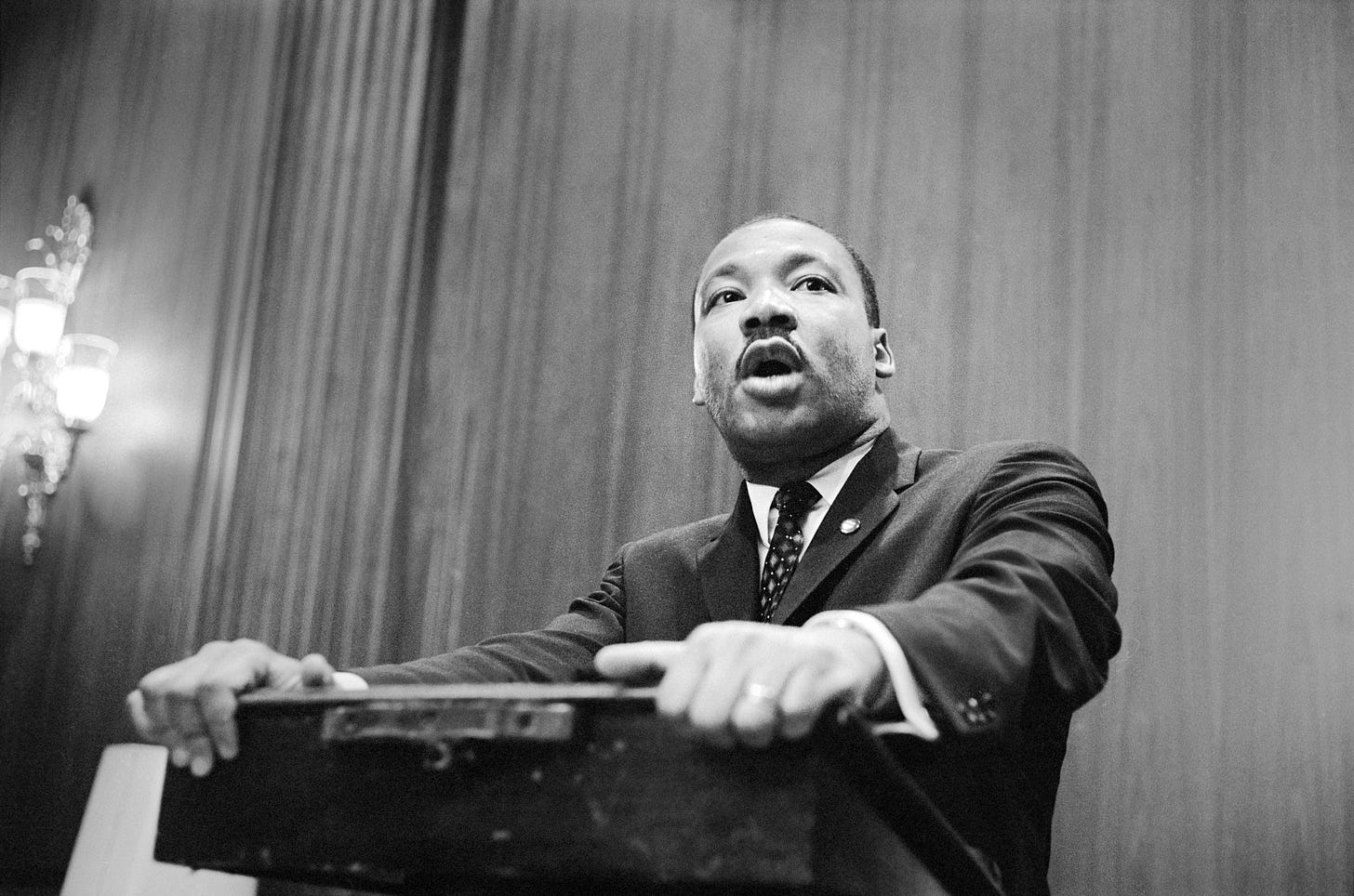

An MLK Jr. sermon sent me down a rabbit hole on the limits of policy

Writing turned me into a vulture.

Every time I read something, watch something, or talk with someone, a part of my mind is constantly cataloging: a turn of phrase I’d never heard before, a word in a new context, an analogy, a random fact.

Being a writer turns every interaction into a scavenging exercise. This made me a more careful listener, reader, and conversational partner, but it also meant I lost something magical that comes with less intentional engagement.

Before I was a professional writer, reading, watching TV, going to church, and listening to podcasts were opportunities to lose myself in someone else’s train of thought. I didn’t pay very close attention to what was happening to me; I just allowed myself to follow where the creator was taking me.

These days, I find myself scavenging constantly, emailing or texting myself fragments of thoughts, or beginning to puzzle through an idea while my pastor continues preaching.

All this scavenging can come in handy. The Argument usually tries to take a break from posting on federal holidays, but I was reading some of Martin Luther King Jr.’s sermons, and the vulture part of my brain lit up.

Written sometime in 1962 or 1963, “On Being a Good Neighbor” laid bare the limits of policy. In it, King recounted the familiar parable of the Good Samaritan, who helps an injured man lying on the side of the road. The Samaritan is not the first or second passerby; a priest and a Levite had passed by him without offering aid.

The sermon revealed two warring impulses in the reverend-activist. He was a man who devoted his life to seeking concrete legal and policy changes and engaging in debates over political strategy, but he also devoted his life to the church, to changing the hearts and minds of men.

King gets at this tension in"On Being a Good Neighbor," where he writes that “a vigorous enforcement of civil rights laws can bring an end to segregated public facilities which stand as barriers to a truly desegregated society, but it cannot bring an end to the blindness, fear, prejudice, pride and irrationality which stand as barriers to a truely [sic] integrated society.

“These dark and demonic responses of the spirit can only be removed when men will become possessed by that invisible, inner law which will etch in their hearts the conviction that all men are brother [sic] and that love is mankind’s most potent weapon for personal and social transformation.

“True integration will come only when men are true neighbors, willing to be obedient to unenforceable obligations.”

The concept of unenforceable obligations King borrowed (scavenged?) from Dr. Harry Emerson Fosdick, a prominent liberal pastor born in 1878 and who died in October 1969. It’s from a Palm Sunday sermon called “The Cross and the Ordinary Man” in which Fosdick distinguished between “enforceable and unenforceable obligations — on the one side, conduct that the laws of court or custom can demand, and, on the other, the ways of living that no laws and no codes of custom ever can require.”

Fosdick argued that lawless criminals are less dangerous to society than people who may be restrained by laws but will never do anything more than what the law requires: “There are many more of them; every one of us is tempted to belong with them — the barely good, who get by on the conduct that is required.”

Fosdick himself was scavenging from Lord John Fletcher Moulton,1 whose speech was recorded and printed in The Atlantic Monthly in 1924 and again in 1942 (perhaps because of the numerical symmetry).

“The real greatness of a nation, its true civilization, is measured by the extent of this land of obedience to the unenforceable,” Moulton wrote. “I am too well acquainted with the inadequacy of the formal language of statutes to prefer them to the living action of public and private sense of duty.”

There’s so much that policy can do to make the world a better place, many things it has yet to do. But policy cannot fill the void that duty has left.

There’s no law that can remove hatred and bigotry from people’s hearts. There’s no regulation that can make you patient with small children in public. There’s no policy that can compel you to treat public spaces with as much care as you would your home.

The law can constrain the worst parts of humanity, but it cannot bring out the best.

Who himself was (sort of) scavenging from William of Wykeham’s motto “Manners makyth Man.” One of the best pieces of advice I can give to other writers is to be less obsessed with originality (and also with getting credit for your ideas).

Great scavenging! One of liberalism’s biggest problems today is that there’s no shared mechanism for inspiring people to meet their unenforceable obligations. A generalized Christian morality served that function in MLK’s day (and in Fosdick’s and Moulton’s). I don’t think it’s an accident that liberalism saw its greatest flourishing when we could count on the law for the enforceable and religion for the unenforceable.

I’m not advocating for a return to a Christian polity, but I do wonder what can serve that crucial function today … and whether a liberal revival is possible without it.

Would love to hear your thoughts.

Good piece. I often wonder what each political side thinks "victory" (if ever attainable) looks like. What will happen to your political foes? On the right, I fear a not insignificant amount harbor visions of leftists imprisoned or cowed into silence through government domination, or at least physical intimidation. On the left, I suspect a few think MAGA will peter out, but there are some that perhaps think they too will be cowed into silence not through the end of a gun, but through social media mobs.

Trump will one day exit off the stage, and perhaps a Democratic president takes over, but what happens to MAGA? Will liberals seek to try to persuade the persuadable, or will they ostracize anyone that goes against liberal orthodoxy? If this is the start of a new MAGA era, does the right think liberal thought should exist? Do they still believe in pluralism?