What if Ozempic doesn't fix literally everything?

Worst Take of the Week: Arthur Brooks is asking the wrong question

Worst Take of the Week is a new occasional column where the author will rant about something we found stupid, annoying, bad, and/or irritating. While the title of this column was necessary for palindromic reasons, I cannot promise that entries will come out weekly or that each piece will literally be the worst take that week; this column would be boring and repetitive if each week I explained why genocide is bad in response to Twitter user @Nazi1488LoveHitler.

Some arguments are bad because the author has made an empirical error. Some of them are bad because the author has bad values. But in his recent columns for The Free Press, Arthur Brooks made a more fundamental error: He asked a bad question.

“Do GLP-1s make us happy?” wondered Brooks, who self-identifies as “one of the world’s leading authorities on human happiness.”

It’s worth taking some time to think through how useless of a question this truly is.

Who cares if GLP-1s make us happy? I’ve never asked myself “Does chemotherapy make cancer patients happy?” or “Does insulin make diabetics happy?” or “Do malaria medications make Nigerians happy?” because the purpose of these medical advancements is to either save people’s lives or make them healthier.

Is it possible that some cancer or malaria survivors go on to be unhappy? I’m sure that some do, but it would never occur to me to evaluate the effectiveness of chemotherapy on this question. The purpose of chemotherapy is to cure cancer, not to give your life meaning.

It’s worth spending some time talking about how bad obesity is. Nearly 500,000 excess deaths in the U.S. happen every year that could have been avoided if Americans maintained healthy BMIs.

For context, in 2020, roughly 70,000 Americans died of an opioid overdose, nearly 600,000 died from cancer, and over 350,000 died from COVID-19. Importantly, some of those COVID deaths and some of those cancer deaths would likely not have happened if not for obesity.

I presume that Brooks would never write a column arguing that cancer patients forgo chemotherapy and instead hustle their way to beating the disease through eating better and exercising more. Of course, this would be impossible, but the same can be said for obesity.

Yes, in theory, most every person should be able to lose weight through exercise and diet, but there are a good many theories that don’t pan out in real life. And there are few things more well-validated in the nutritional sciences than the finding that most diets fail.

Probably the most widely cited research on the fact that diets usually fail is the boringly but appropriately named “Maintenance of Lost Weight and Long-Term Management of Obesity.”

While dropping some weight, including pretty substantial weight loss, is certainly possible through a variety of diets, within five years, more than 80% of lost weight will be regained. The entire article went into the physiological and environmental reasons behind this problem, and it’s pretty accessible to nonresearchers, so if you’re interested (and I hope you are, Arthur) you can go read it!

One study that looked into the roughly 20% of overweight people who are successful at losing and keeping at least 10% of their initial body weight found that it requires an extraordinarily high level of willpower. These people are exercising roughly an hour a day and maintaining a low-calorie, low-fat diet with a high degree of vigilance in monitoring their body weight.

But the facts are incontestable: For whatever reason, the vast majority of people who are desperately trying to lose weight, who are steeped in a society that reminds them constantly of the physical, social, and emotional harms of remaining overweight, are unable to do so.

These facts should make one curious. They should make one interested in new and exciting solutions to this seemingly intractable problem that increasingly afflicts people the world over.

Unfortunately, many people prefer confirmation bias to curiosity.

The GLP-1 revolution is not a miracle. It’s a helper.

Given these sad facts and the reality of rising obesity rates, GLP-1 drugs are a modern marvel.

They help people lose weight, yes, but studies have found that this weight loss is sustained with continued treatment. While semaglutide (Ozempic) averages about 15% of mean weight loss, tirzepatide (Zepbound) averages about 20%, and Eli Lilly’s newest drug may even help obese individuals lose almost 30% of their starting weight.

Not only do these drugs help people lose and keep off weight, they reduce the rate of strokes and stroke-related deaths, they slow the progression of chronic kidney disease, they cut the incidence of heart attacks, and it’s possible they may even help reduce dementia risk and addiction.

Brooks’ main point is that GLP-1 drugs offer you “weight loss without struggle” and that “satisfaction is the joy you get from an accomplishment after struggle.” He went on to point out that while there’s nothing wrong with taking Ozempic “this is hardly evidence to yourself that you are a person of character and strength.”

I think many of my previous arguments apply here, but in addition, I think Brooks carries a fatal misunderstanding of how GLP-1 drugs actually work.

Ozempic and Mounjaro are not magic drugs that make excess weight vanish. Users still need to follow a diet and exercise plan to achieve their goals.

These drugs work to “reduce food cravings, increase fullness, slow digestion, and help with blood glucose control.” But as basically any modern human in a developed nation understands, it is possible to eat a lot of food even if you are full and have no cravings. And nothing can make you lace up your running shoes or hit the gym; these are still choices individuals have to make. GLP-1 agonists just lower that bar from “nearly impossible” to “possible with reasonable effort.”

When normally dieting, people lose weight but then get hungrier, which is a part of why it’s so hard to maintain that consistency. One study found that “weight loss leads to a proportional increase in appetite resulting in eating above baseline by ~100kcal/day per kg of lost weight – an amount more than 3-fold larger than the corresponding energy expenditure adaptations.”

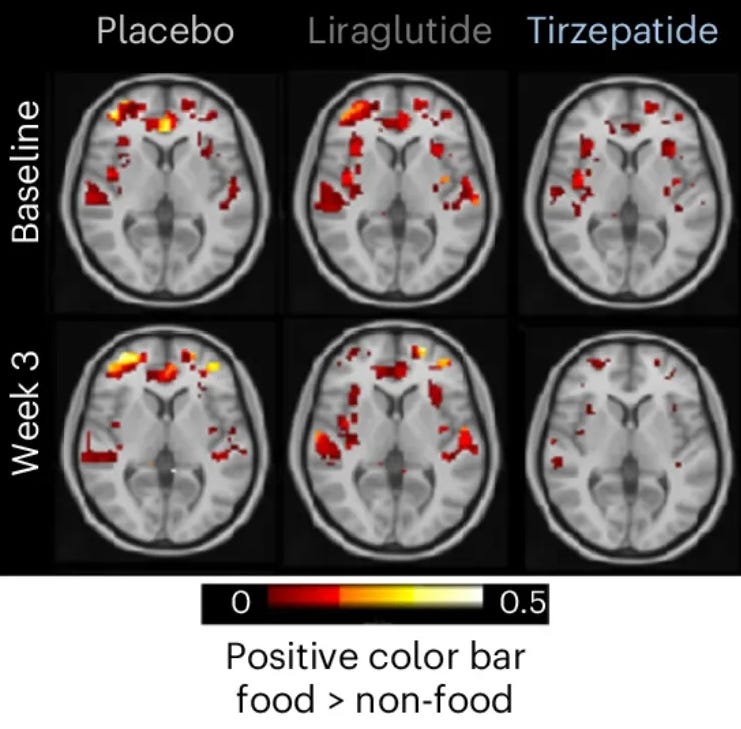

On Dr. Ashwin Sharma’s great newsletter, GLP-1 Digest, Sharma pointed readers to a “groundbreaking randomized controlled trial” that included scans of “people’s brains in real-time as they looked at images of high-calorie, high sugar foods (think pizza, cakes, burgers etc) while taking tirzepatide, liraglutide, or a placebo.”

So yes, current GLP-1 agonists are not magic pills. But, honestly, I’m fine biting the bullet: it would be fantastic if they were. Even if a single pill could cure you of obesity or heroin addiction or cancer or smoking, unlike Brooks I am not worried about robbing you of whatever satisfaction you might get from the hard slog of quitting unaided.

Sometimes things aren’t complicated: good things are good and bad things are bad

OK OK but … do GLP-1s make you want to kill yourself?

While I think the question is orthogonal to the main point of GLP-1s, Brooks did highlight a study showing that GLP-1 use is associated with increases in reported depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors. These are scary findings with reasonably sized effect sizes.

After citing this research, Brooks concluded that the “jury’s still out” on whether GLP-1s will raise users’ well-being. But the juries are very much not out. Two of them have come back. And the verdict? Total exoneration.

In fact, days before Brooks published his column highlighting this study, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration published its findings showing that after “comprehensive FDA review” there was “no increased risk” of suicidal ideation or behavior and requesting that the warning label should be removed from these products.

This review went over observational studies, case reports, and clinical trial data, as well as a comprehensive meta-analysis that included 107,910 patients and a retrospective cohort study that included 2.2 million users, neither of which found an increased risk of suicidal ideation or behavior.

Perhaps Brooks could be forgiven for missing this update, but in April of 2024, the European Medicines Agency — a decentralized EU agency responsible for “scientific evaluation, supervision and safety monitoring of medicines” — concluded that the existing evidence did not support a causal association between GLP-1s and “suicidal and self-injurious thoughts and actions.”

This is not even mentioning a May 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis that found GLP-1s were not associated with increased risk of psychiatric adverse events. There are other papers, but instead of grappling with this research, Brooks poked fun at some rodent studies, quipping that it seems hard to “tell when a rat is feeling depressed.”

Life is hard for thin people, too

Brooks’ problem is that he seems to think humans lack opportunities to exert willpower and discipline. Yes, overcoming adversity is important to living a good life, but we live in a fallen world, and there will always be adversity — we don’t need to manufacture it.

How do I know this? Because the majority of Americans are not obese and still have to face the normal human problems of working a job, finding a partner, making and keeping friends, and getting triggered by widely read and badly reasoned articles.

A perennial problem for take-slingers, of which I am one, is that most of the important questions are boring. For instance, does B6 compounded tirzepatide perform better than Zepbound? Can newer GLP-1 agonists prevent the loss of muscle mass? Or should the government cover Ozempic-for-all?

I could list 5000 questions I have for researchers about the science of obesity, and at no point would I alight on: Should we worry that the miracle wonder drug eliminating the leading cause of preventable deaths works too well?”

More on public health:

The toxic modernity narrative

On Tuesday, The Guardian published the best news I’ve heard all year: The microplastics panic was based on dubious science.

Most Americans support some vaccines. We can work with that.

Welcome back to The Argument’s monthly poll series, where we survey Americans on the issues everyone’s fighting about. Our last surveys have asked about immigration, AI, and free speech. Our full crosstabs are available below the paywall in this post

When I'm manic, I get very, very skinny, sometimes frighteningly so. When I'm on meds, I get fat. I'm not trying to get thinner in the former instance, and I'm REALLY not trying to get fat in the latter - I have worked so, so hard with diet and exercise, and I can never win against the effects of my meds. And these experiences have made me forever aware that the moralizing vision of obesity is just fucking wrong. Our bodies react very differently to similar behaviors when it comes to weight loss. What cruelty to tell people who have found something that finally works that it's "spiritually deadening" or whatever the fuck.

Over the course of about 4 years I lost 270lbs, going from 522 to 250. I reached my low last April and it was great, but I’m now back up to around 325, having regained 70-80lbs in about 8-9 months.

The problem I ran into was that 1) my willpower was exhausted but 2) I still have that disregulated appetite that made me super obese to begin with. If I eat a very bland, low processed, high protein, low carb diet, I can kinda keep my hunger and eating in check. During my loss I locked down my whole life and oriented my entire self towards my #1 goal of weight loss. Once I’m in maintenance the decisions of when to abstain and when to indulge become arbitrary in a way that’s been hard for me to navigate. So if I allow more foods in, it’s a real short road to get to my body urging me to eat 1-3k calories OVER my maintenance. My body and mind just orient me towards eating, mostly junk food, but eating a lot nonetheless. And I’m now in a position where I can’t make weightloss my all-embodying life orientation anymore, so it’s been hard!

So while it’s been disheartening to regain and have to do it again, I’ve got a doc appointment coming about getting on a GLP. I showed I can do the work, can build the discipline, but I can now take a drug that fixes the exact thing that’s wrong with me. I’m planning to write about my experience after, I’d love to live a life not dominated by my struggle with food anymore.