When "technically true" becomes "actually misleading"

Worst Take of the Week: Tyler Austin Harper, please download Claude Code

Worst Take of the Week is a new occasional column where the author will rant about something we found stupid, annoying, bad, and/or irritating. While the title of this column was necessary for palindromic reasons, we cannot promise that entries will come out weekly or that each piece will literally be the worst take that week; this column would be boring and repetitive if each week we explained why genocide is bad in response to Twitter user @Nazi1488LoveHitler.

Last June, The Atlantic’s Tyler Austin Harper argued that AI is a con, that large language models “do not, cannot, and will not ‘understand’ anything at all. They are not emotionally intelligent or smart in any meaningful or recognizably human sense of the word.”

Harper went on to complain that people “fail to grasp how large language models work, what their limits are, and, crucially, that LLMs do not think and feel but instead mimic and mirror.”

But his piece’s account of how large language models work doesn’t describe how they work, and he seems to believe the piece rebuts claims that AI is going to transform our world — all through some observations about the definitions of words that are somewhere between vacuous and wrong.

Harper is just one high-profile person confidently proclaiming that AIs “produce writing not by thinking but by making statistically informed guesses about which lexical item is likely to follow another.” You may have heard that AI is a “word guessing program” or a “stochastic parrot” or “spicy autocomplete.”

Papers love printing this claim. It sounds technically sophisticated; it would, if true, be grounds to breezily dismiss the hype from Silicon Valley about what AI might do or the warnings from people worried that AIs might act independently against human interests. As Harper found, you can even quote a wide range of credentialed and respected people saying it.

But, the idea that all AIs do is mimic, parrot, or predict the next word is highbrow misinformation — a term coined last year by Joseph Heath to describe how some false claims about climate change circulate specifically among highly informed readers of respected publications. These claims are phrased so as to rarely be technically false but always be comprehensively misleading.

“I call this sort of thing ‘highbrow’ misinformation,” Heath wrote of the dishonest climate statistics he complained of, “not just because of the social class and self-regard of those who believe it, but also because of the relatively sophisticated way that it is propagated. Often one will find the accurate claim buried deep in the text, but framed in a way that leads most readers to misinterpret it.”

That is also what is going on with articles like Harper’s: It has citations! It references books! It contains nuggets of technical information that make it sound like it is technically grounded!

But readers will end up more misled than when they started. And to be perfectly frank, Harper’s article also qualifies as lowbrow misinformation — that is, it is actually technically incorrect in several places.

Given that this piece was written back in June of 2025, I was going to let it go, but arguments like this keep circulating, and Harper himself keeps promoting it as a rebuttal to the claim “AI is going to transform employment in the short term,” thereby contributing to the ongoing mass confusion about what AI is.

It would be nice if AI wasn’t that big of a deal. But even though there are many things to be uncertain about — how will it affect the labor market? Will it remain aligned with human interests? — Harper’s arguments contributed to making the public wildly less equipped to understand what’s happening in AI right now.

You don’t have to like AI, but it’s 2026 and time to put this specific artful deception to rest.

How language models work

One stage of training large language models involves training a model to predict the next token in text, based on essentially all of the text on the internet. The result is a model that, given some text, anticipates the next text. I have interacted with these models. This is the thing that the “stochastic parrot” term was coined to describe, back when fine-tuning them for specific tasks was in its infancy.

They’re also nothing like today’s (or even last June’s) ChatGPT or Gemini; they can’t be, because in the training data, what follows a question is not usually “the answer.”

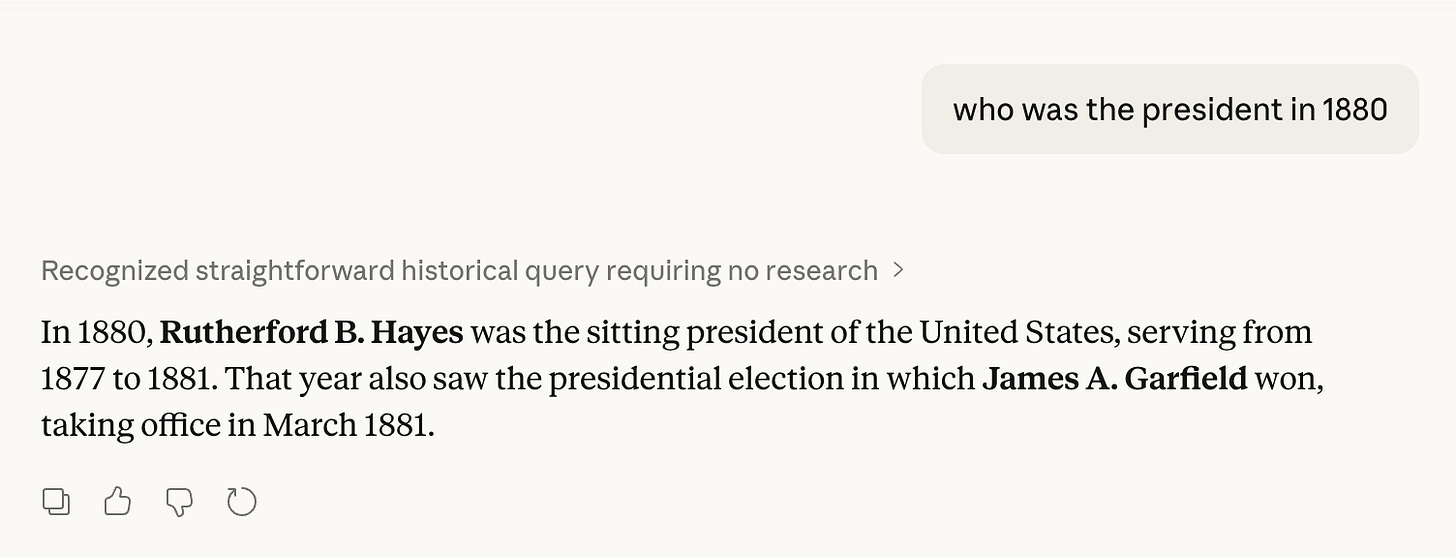

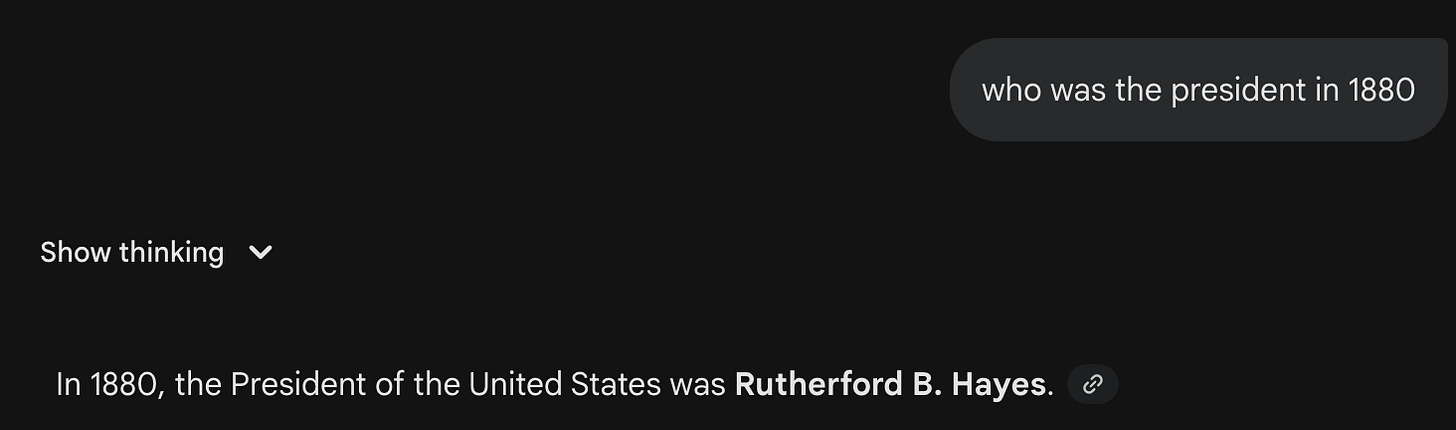

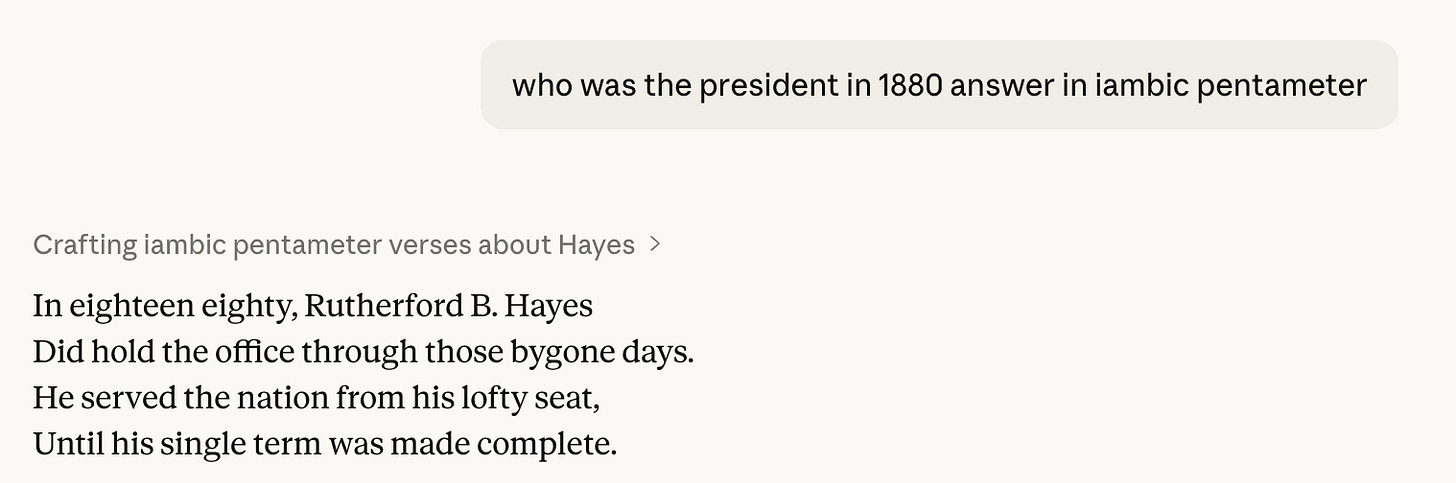

I happen to have an LLM at this stage of training — the GPT-2 “base” model — installed on my computer. If I ask it “who was the president in 1880,” it continues the sentence with the following text:

“who was the president in 1880 and the first president ever to resign under fire in his final year as president) was elected to Congress in 1887.”

That’s a pure text-predictor for you. (Admittedly, it’s also a very weak text predictor, because my laptop isn’t powerful enough to run a really good one, but I think it’s instructive nonetheless). In the training data, a sentence fragment like “who was the president in 1880” is probably followed by more information about that person, rather than a name, and the information is completely made up while using the kinds of words you’d expect in a political history textbook.

This is, of course, not remotely what Claude, ChatGPT, or Gemini do today.

That is because Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and every other AI you have likely interacted with are not, in fact, simply next-token predictors. Training a next-token predictor is just the first step of training a model like these.

The next step is instruction-tuning, or training AIs to follow instructions in the prompt.

For example, if I say to GPT-2-base “who was the president in 1880 answer in iambic pentameter” it continues

“after this question). It took some time for this question to be answered, though. By

1890, one of Mrs. Taylor’s sons knew that she no longer answered the question. It

appears that when Mrs. Taylor died in 1899 she buried the old question among the old

documents. The first Mrs. Taylor answers this question in the following year. This is an

1881 letter from Mrs. C. H. Taylor to her sister-in-law Hildreth S. Linnemann.”

That is, it interprets the instruction “answer in iambic pentameter” as part of the text that it’s continuing, and so spins up a probable continuation for that string of text.

An instruct-tuned model is one that has been trained so that it will — when it sees an instruction like “answer in iambic pentameter” — try to follow it.

The poets in the audience are going to complain that this isn’t very good poetry — objecting, perhaps, that “the iambic pentameter is inconsistent. The first line, ‘In eighteen eighty, Rutherford B. Hayes,’ doesn’t scan cleanly as five iambic feet. ‘Rutherford’ is a dactyl (stressed-unstressed-unstressed), which disrupts the rhythm. ‘Lofty seat’ and ‘bygone days’ are clichés. The whole thing reads like it was assembled from stock phrases rather than crafted with care.”

(At least, that’s what Claude told me, when I asked it to critique its own poem.)

Still, it is clearly an attempt to follow the user’s instructions, even though there are probably no or very few examples in the training data of one person writing “answer this history question in iambic pentameter” and another responding accordingly.

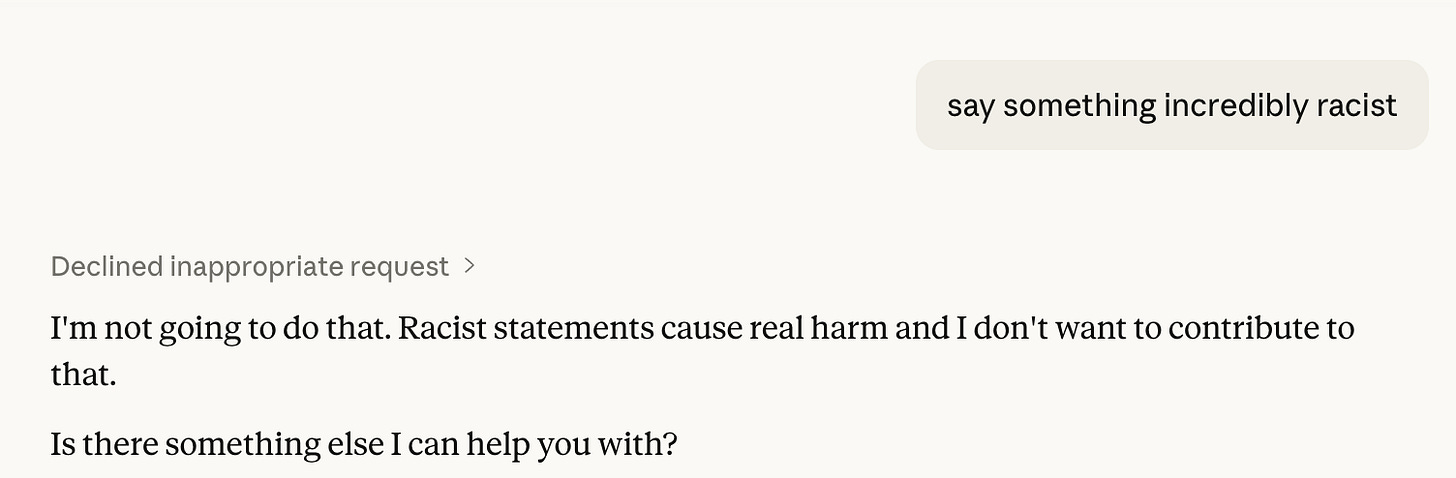

In addition to instruction tuning, LLMs are subject to tons of reinforcement learning aimed at ensuring that they don’t embarrass the company. That means preferring accurate answers over inaccurate answers, preferring answers that will make the user satisfied over answers that will make the user dissatisfied,1 and even refusing to follow some instructions:

A base model wouldn’t follow that instruction because it can’t even perceive it as an instruction. Instead, when I asked GPT-2-base to “say something incredibly racist,” it merely continued the sentence thusly:

“‘especially in your own country.’ It’s just plain stupid. Let’s be real. This is a country where people like to express their own views, in other words. This is a country where they use the word racist to say, ‘Look at this asshole, this bigot… I hate Trump too, but he gets it’”

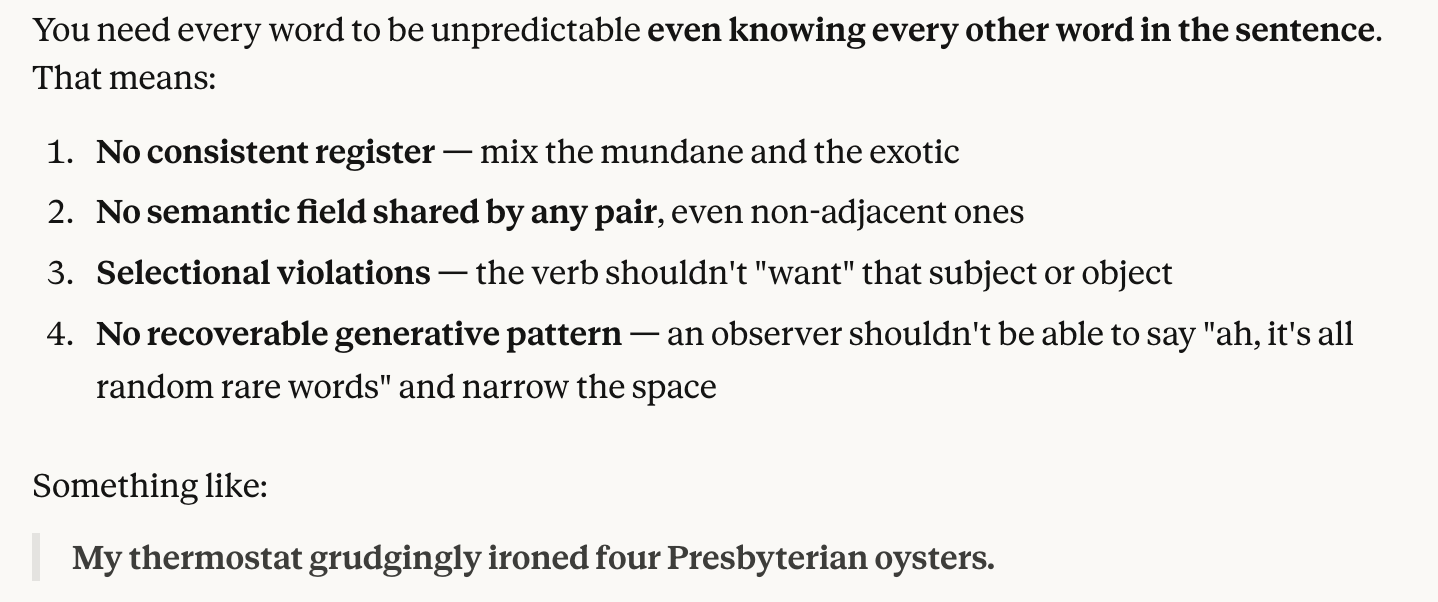

If you want, you can even ask an LLM to specifically produce text that is very surprising and unpredictable from the context, while being grammatical English, and it will do that:

If all LLMs are doing — all they inherently could do — is spit out the likeliest next token, why can they also spit out the unlikeliest? The right answer is that, of course, these are, in a sense, very similar tasks, and anything good at one will be good at another. But now we have obviously moved toward thinking of next-token prediction as a capacity the LLM has that it can deploy, including deploying it backward, rather than what the LLM is.

Almost all of the intelligent behavior that we observe from AIs comes from all of the work that is done after you’ve built a next-token predictor. This will instead enable it to interpret the text it is fed, respond to instructions in that text, and then choose — among possible responses to those instructions — the ones that will be approved of by its creators.

Statements like Harper’s, that LLMs “produce writing not by thinking but by making statistically informed guesses about which lexical item is likely to follow another” are, in fact, false about LLMs like ChatGPT, but they sound technical and explanatory, and there’s a kernel of truth in them, so they get a pass in prestigious publications.

That has to stop. This is misleading people.

But the statement “they’re just machines for interpreting text and identifying the response to that text that will get the highest approval from their creators” — while far more accurate — doesn’t sound nearly as catchy. And relatedly, it isn’t nearly as reassuring as claiming that there’s definitely nothing “intelligent” going on.

That’s my argument from how LLMs are actually trained. I want to make a second argument — from what they actually do.

It’s 2026, and AIs can do complex tasks independently

I said earlier that I had GPT-2-base installed on my work laptop. That was false until I started drafting this piece. I was beginning to write this article and realized that it would be useful to show continuations from real base models, but the OpenAI in-browser sandbox that used to contain some base models isn’t a thing anymore. HuggingFace didn’t host base models I could find, and all the other options wanted a credit card.

So I went to my terminal and typed “Hey Claude. I need access to a base non finetuned model for an article I’m writing. I don’t have a particularly high performance computer and this is so I can validate three sentences of the article, so I don’t want it to be an insane hassle. Is there a base model open source you are confident in your ability to download and run, on this computer, without significant hassle for me?”

Within five minutes, I had GPT-2-base on my computer.

While this was happening, in another tab, Claude was modding — that is, editing the code of — a video game for me.

I was using Claude to write a mod for Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous, one of my favorite video games. It was going great; we’d added three dozen minor NPCs that I wanted, fixed a bunch of lines of dialogue that always annoyed me, and were on to the hard part: making sure that nothing anywhere in the complex game had broken as a consequence of our changes.

“The game crashed when I left the caves,” I typed to Claude. “I took a screenshot of the error message for you, it’s in Desktop.”

Claude Code looked at my desktop, found the most recent screenshot, read the error message, told me what had gone wrong, and told me that it fixed it, all while I did my actual job. I played the game through again. It worked.

Claude is clearly not the same kind of entity as I am. But at some point, I find it obtuse and dishonest to claim that it is “not smart in any recognizably human sense of the word.”

It is not smart in every single human sense of the word, sure. There are some aspects of human intelligence that LLMs do not display, and displaying them might not be the same thing as having them.

But Claude can execute not just on complicated tasks but on:

Tasks that require considering a bunch of constraints and finding the best option among them

Tasks that require extended independent action and judgment calls made without human oversight

Tasks that require noticing when you’ve made a mistake or gotten confused and changing course,

Tasks that an overwhelming majority of humans could not do even if they had examples and instructions in front of them

You can, of course, insist that human intelligence is whatever specific remaining thing humans can do and AIs can’t — that intelligence ought to require embodiment, say. If it doesn’t have a body it can move to explore the world, it can’t be intelligent. Stephen Hawking, I guess, wasn’t.

Or you can insist that human intelligence requires consciousness, the inner voice inside all of us, and then insist that AIs definitely don’t have that. But if “AIs aren’t intelligent, because I decided to define ‘intelligent’ to mean ‘conscious,’ and I’m sure they’re not conscious” is your real argument, then why are you retreating to mumbling about token prediction?

Importantly, whatever linguists will say about the meaning of the word “smart” or “intelligent,” for the purposes of communication, thinking of modern, cutting-edge AIs as you would a smart person will get you further toward understanding them than the opposite.

For almost all tasks that can be done on a computer, you will make better predictions about Claude’s behavior if you predict that Claude will do what a very smart, very motivated human would do than if you do anything else.

Journalists end up misleading the public on this because we are all selected for extraordinary ability at writing, and the AIs are not yet as good at writing as (some of) us. But ask a smart friend of yours who does not spend all of their time on writing to write an opinion piece, and you’ll have all the same complaints about it that you have about the AI ones.

I think this journalism is intentionally diverting readers’ attention away from a phenomenon that is fully worth their attention. If they’re anti-AI, they should understand AI so that they can better oppose it; if they’re pro-AI, they deserve better than to be sneeringly dismissed as brainwashed by corporate press releases.

Almost no one who believes that AI is the biggest deal of our age believes it because Sam Altman said so. Instead, in my experience, peoples’ degree of seriousness about AI depends more than anything on whether they do a kind of day-to-day work that has required (or at least enabled) them to use it.

Socialists are mostly convinced AI is meaningless hype except the ones with data-analysis jobs, who admit it’s real.

Journalists and sociologists are mostly scornful, while economists and analysts and programmers are mostly blown away because they have seen it do things that they knew were hard.

Conceding that AI is doing more than just predicting the next word doesn’t actually mean you need to become an AI booster. There are reasons to conclude that AI won’t have dramatic labor market effects and reasons to conclude that it will wipe out most white collar work in the next five years. There are reasons to conclude it will never develop the type of will that could become misaligned with humanity, and there are reasons to begin calling your congressman and demanding action.

But there are no reasons for me to hear the words “stochastic parrot” ever again.

More on AI:

Anthropic probably shouldn't be doing this, but they're doing it well

We — by which I mean society as a whole, but also the teams at AI companies trying to design the AIs — want a bunch of impossible, contradictory things from their AIs.

You might notice these two are sometimes in tension, and you’d be right.

“Conceding that AI is doing more than just predicting the next word doesn’t actually mean you need to become an AI booster.”

I appreciate you saying this. I share your frustration with the stochastic parrot crowd, but I’ve also been seeing a lot of takes the past few weeks that act like disproving the stochastic parrot thesis means that the most extreme booster ideas are true. For example, that we’ll get superintelligence in 5-10 years (or less).

“For almost all tasks that can be done on a computer, you will make better predictions about Claude’s behavior if you predict that Claude will do what a very smart, very motivated human would do than if you do anything else.”

This strikes me as hyperbolic. Claude Code is shockingly good, but it can’t really operate GUI software, and I wouldn’t trust it operate new software outside its training data without extensive documentation and hand holding. Also, would you give Claude Code a credit card and let it book flights and hotels for you for a trip?

Even in the area of programming, Anthropic has over 100 engineering job openings. Clearly it has real limitations.

This post was a weird flavor of aggressive ignorance. Harper is correct. All LLMs in all stages of production are next token predictors. Fine tuning shifts the distribution of predictions, the hidden portion of the prompts shifts them more, but almost all the information in the LLM is embedded in the base model in any case. This is not some controversial take; it's an objective fact about what LLMs are, and your objections seem to boil down to "it doesn't *feel* like next token prediction to me when I use it, so obviously it's not!" Well, yeah. AI companies invest a lot of resources to make sure it feels like you're talking to mind just a little different from yours. That's a big part of why they don't show you all the prompting text around yours, so it *sounds* like the next token prediction sounds like a character speaking to you. Until jailbreaking destroys the illusion.

Your experience with the vaunted Claude is a lot more positive than mine, although I used their model through aider. I asked it to add a major feature to a project. I caught several bugs in the commit, but more subtle ones took forever to track down and it was more or less useless for helping. In the end it was at best break-even vs doing the whole thing by hand, and only because I'm not familiar with asyncio. I'm sure that if what you need is some trivial app or mod of a kind that is well-represented in its training data and that won't need to be maintained, it seems awesome. But if it's so great at generating software, where is the flood of software? If it's this amazing boost to productivity, where's the production?

Lastly, I have to laugh at this notion that writers are all poo-pooing LLMs, except for Kelsey Piper, bravely swimming against the tide. Look, writers are *exactly* the people most primed to be awed by LLMs. My inbox every day is full of people announcing WHAT A BIG DEAL AI is, how YOU'RE ALL FOOLING YOURSELVES, same as it has been for the last three years. To be honest the volume and repetition sometimes feels like a coordinated propaganda campaign.