Why women should be techno-optimists

Technology is about liberation

Welcome back to The Argument’s monthly poll series, where we press Americans on the issues everyone’s fighting about. Last time it was free speech. This time it’s AI. Our full crosstabs are available for paying subscribers here and our methodology can be read here.

An awkward stylized fact about support for new technology is that in poll after poll, women tend to sound a bit like luddites.

In The Argument’s new poll, for instance, we asked respondents whether their city or town should allow or ban self-driving cars. As my colleague Kelsey Piper wrote yesterday, no subgroup had majority support for the idea, with just 28% of people choosing allow and 41% choosing ban (the rest said they weren’t sure).

Looking deeper at which subgroups were driving this pessimism, I was unsurprised to find gender jump out vividly: While 39% of men wanted to allow self-driving cars, just 19% of women said the same. On the flip side, 48% of women wanted to ban the technology compared to just 32% of men.

I’ve seen gender splits when it comes to technology before. For instance, a March 2025 Gallup poll showed the highest support for nuclear energy in 15 years, but while 41% of men said they “strongly favor” its use “as one of the ways to provide electricity,” just 16% of women agreed. Regarding self-driving cars in particular, a 2021 Pew poll found men were both much more eager to ride in them and viewed their spread as a good idea for society.

An anonymously written article in Aporia Magazine, an outlet that has published many articles on the biological differences between genders and races, argues that declining economic and technological progress is the result of “feminization” — that is, the increasing cultural and political power of women. According to the author, women are more likely to be opposed to a variety of innovations because we are “psychologically more predisposed to (small-c) conservativism [sic] than men and hence opposed to progress.”

The conclusion of this article is predictably cowardly. Mr. (I’m presuming) Anonymous doesn’t want to come out and say: “It’s time to send women back to the home where they belong.” Instead, he writes that “rolling back the worst parts of the regulatory explosion may matter on the margin, but it’s nowhere near enough to bring the West back to the pre-1960s trend. The population aging, between-population dysgenics, institutional rot and cultural malaise (the subject of this article) we face all come back to that same critical decade. The whole thing’s got to go.” (emphasis added)

Now, this is just one anonymous internet article from a small magazine.1 But I’ve noticed a growing sense of, if not outright biological determinism, then fatalism about women’s opinions toward technological progress. Peter Thiel, for one, has echoed a version of this argument. While on Joe Rogan’s podcast last year, he speculated that technological stagnation could be due to the fact that that the U.S. has become a “feminized, risk-averse society.”

Now, it is prima facie ridiculous to argue for progress by … trying to turn back the wheel of progress.2 But more to the point, this line of thinking is also just deeply lazy. Women have arguably been the greatest beneficiaries of our technological advances, and before anyone concludes that the only way to build nuclear power, expand driverless cars, or achieve abundance is to return women to the home, I think tech optimists should try making some better arguments that actually tap into that history.

Technology is an instrumental good

As someone who took an advanced inorganic chemistry class pass-fail for fun in college, I understand the appeal of being interested in science for its own sake. But no matter how intrinsically cool invention is, the single coolest thing about technology is that it makes people’s lives better. The coolest things about self-driving cars are that they save lives and they save people time. The coolest thing about nuclear energy is that it provides energy without emitting carbon and without taking up a lot of land. Rinse and repeat with basically every useful invention: It’s cool because it helps people do more of what they want to do and less of what they don’t want to do.

What is most interesting about gendered opposition to new technology is that women’s liberation was predicated on the invention of new technologies. As Nobel Prize winning economist Claudia Goldin has argued, the creation and spread of the birth control pill was instrumental in allowing women to gain power over their own family planning decisions and thereby plan for a career.

But even beyond that, so much labor-saving technology has specifically freed women from the drudgeries of life: the dishwasher, the washing machine, the school bus, the vacuum, water systems, preservatives in prepared foods. It is astounding how many innovations have specifically given women back the most precious commodity of all: their time.

In 1912, Thomas Edison talked to Good Housekeeping to push the marvel of electricity:

“The housewife of the future will be neither a slave to servants nor herself a drudge. She will give less attention to the home, because the home will need less; she will be rather a domestic engineer than a domestic labourer, with the greatest of all handmaidens, electricity, at her service. This and other mechanical forces will so revolutionize the woman’s world that a large portion of the aggregate of woman’s energy will be conserved for use in broader, more constructive fields.”

Can you imagine our tech CEOs going on Good Housekeeping today to talk about how their products will similarly liberate women? The case is certainly available to them:

Self-driving cars can not only save everyone time but also free women, who do the majority of child care, from having to choose between driving their child to basketball practice and finishing up a project for work — or even actually getting to hang out with their kid rather than getting stressed out by traffic.

The most common complaint about self-driving cars is safety. To be honest, I don’t think it’s insane to be cautious about a new technology that attempts to automate the most dangerous part of most people’s day. But it’s entirely possible to overcome those concerns. As Kelsey pointed out, recent data indicate that “80% less likely to get into a serious crash than human drivers".”

Not only that but autonomous vehicles are a potential boon to women’s safety as passengers. Ride-sharing and cabs have long been seen as a potential site of victimization. Earlier this year, a New York Times investigation revealed a disturbingly high rate of sexual assault and misconduct in Ubers. Over the five years from 2017 to 2022, more than 400,000 reports of sexual assault and misconduct were lodged. The company claims that 75% of those were “less serious” incidents, like explicit language. But I can tell you from personal experience that it’s hard to tell when it’s happening whether some disturbing talk is going to turn into something more sinister.3

Technology as the great equalizer

I recently acquired an e-bike and it has been a genuinely transformative experience. When I was 21, before D.C. had built many of its bike lanes and before I had ever heard of an e-bike, I spent my entire summer biking back and forth to work with the Capital Bikeshare because it was incredibly cheap and all I had was an $800 monthly stipend — 100% of which was going to pay for my half of a small bedroom.

During that summer, I nearly got hit by a car at least three times and realized that showing up to work with my hair frizzy from the D.C. humidity and drenched in sweat on a regular basis was perhaps not displaying the appropriate amount of professionalism. One of my colleagues, a man, also biked to work, but due in part to his greater strength, less frizz-prone hair, and the normalization of men arriving to work kind of sweaty from biking, he received fewer comments about his appearance.

I stopped biking to work.

My e-bike has changed all that. It’s a pedal-assist bike that allows me a wide degree of granularity in how much assistance I want (from absolutely none to more than doubling my strength). That means if I want to take my e-bike to an important business meeting, I can. If I want to do a fun long-distance ride for exercise, I also can.

But perhaps the most transformative thing about the e-bike is its psychological impact: My husband, an avid biker, will ride next to me sometimes. He likely has more than twice my strength, and sometimes when we’re going uphill, I’ll crank up my e-bike’s assist and we’ll laugh as I quickly pass him.

There’s a certain exhilaration in getting to bike very quickly and in not worrying about whether you can handle a difficult journey. Of course, there are many women much stronger than I, but on average, women are less physically strong than men. That means the range of what I consider a fun Saturday bike ride used to be quite different from my partner’s. Not anymore.

Technology as the great equalizer is not something I came up with, not even with bikes in particular.

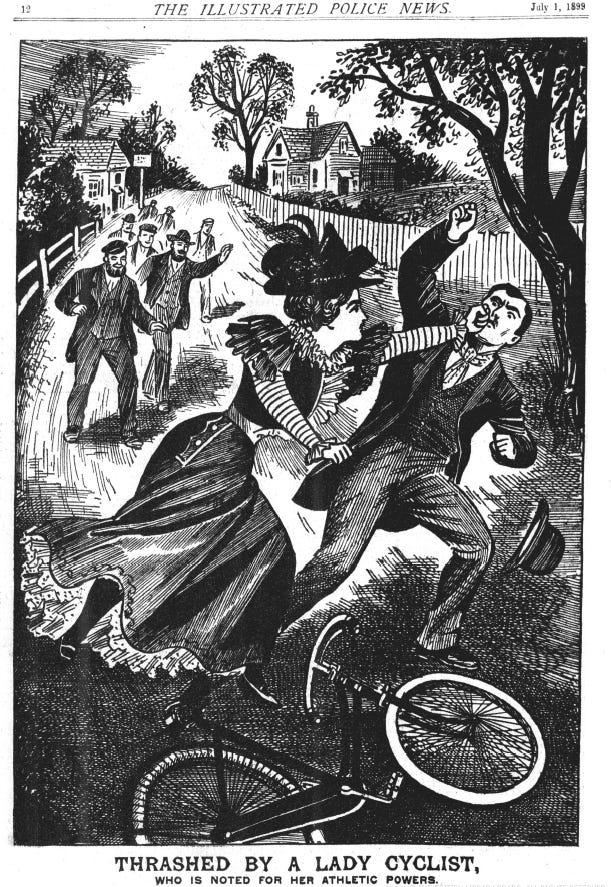

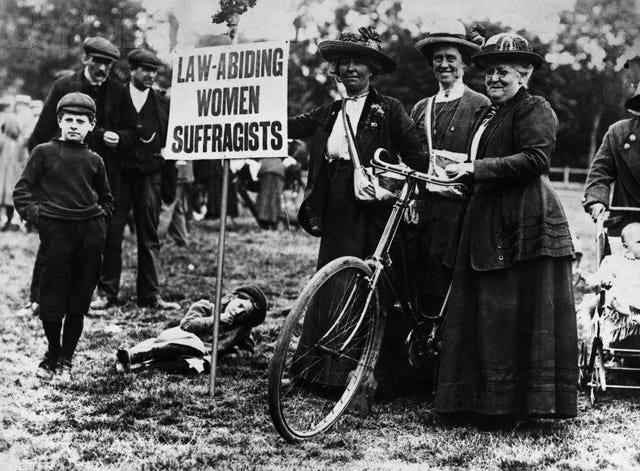

More than 100 years ago, my foremothers were having a very similar experience with the widespread adoption of the bicycle in the early 20th century. As Adrienne LaFrance wrote for The Atlantic, the bike had become “an enormous cultural and political force, and an emblem of women’s rights.” LaFrance quotes an 1895 Pennsylvania newspaper, which remarked that “the woman on the wheel … is riding to greater freedom, to a nearer equality with man, to the habit of taking care of herself, and to new views on the subject of clothes philosophy.” This last point is a reference to how the popularity of bikes pushed women’s clothes away from the overly restrictive Victorian garb that had previously constrained their bodies and movements.

The widespread adoption of a labor-saving technology, not just used by women but welcomed eagerly, pushes against the idea that women are inherently opposed to new technologies.

Women are persuadable

As Kelsey mentioned in her piece yesterday, regional divergence in support of autonomous vehicles indicates that places where the technology has been deployed (the West) are significantly more likely to support them. Exposure therapy!

I asked Lakshya Jain, our director of political data, to look at whether women’s support for self-driving cars looked different in the West compared to the rest of the country. For women in the Northeast, South, and Midwest combined, 51% were in favor of banning autonomous vehicles, but for women in the West, that opposition dropped to just 38%.4

I think, broadly defined, technologists and techno-optimists need to realize that the way we talk about innovation in articles, in ads, and in manifestos is often suboptimal for the goal of trying to convince skeptics of the value of progress. Take this 2023 “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” from Marc Andreessen that speaks in grandiose terms about the value of technology. I agree with much of what he writes, but it reflects an orientation toward scientific achievement that is more focused on the adventure of invention than it is the point of all that progress.5

Pop quiz! Which of the following is more likely to convince a safety conscious, techno-pessimist?

Andreessen paraphrasing another manifesto to argue “Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Technology must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.”

Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) arguing that autonomous vehicles “can eliminate behavior-based traffic deaths, including drunk driving fatalities. MADD will continue to strongly support the safe development of this technology and work to build public acceptance for the adoption of autonomous vehicles.”

The broader problem for technologists is the widespread impression that their “progress” is merely about accomplishing something technically impressive even if that breakthrough has limited or destructive impacts on humanity. I don’t care that it’s incredibly difficult and impressive to create addictive short-form video platforms, I care that it’s wasting our time. I don’t really care if Mark Zuckerberg is a genius if the impact of his brilliance has been to create platforms that degrade social trust.

I want a techno-optimism that is focused on human progress. I want vaccines and geothermal energy and supersonic flight and high-speed trains. I want to venerate the boring technological achievements like the doctor who halved the C-section rate at his hospital and lowered the maternal mortality rate in California by recommending a “hemorrhage cart” that prevented new mothers from bleeding to death. Technology isn’t just about pushing the frontier. It’s about making people’s lives better.

I have made a career out of investigating the problems behind America’s turn against growth: housing, energy, transit, productivity, and technology. Opposition to the types of progress that make people’s lives better fills me with frustration. But the impulse to turn to repression in order to achieve progress is not only wrong, it is a woeful misunderstanding of what has made America an unparalleled technological giant.

The idea that getting things done, building big projects, and achieving societal greatness is incompatible with egalitarianism is not only morally bankrupt, it’s factually wrong. Reactionaries point to China’s high-speed rail network while conveniently ignoring Italy’s, France’s, and Germany’s. If women’s liberation is why Americans can’t generate enough energy, then why is Iceland — which is renowned for integrating women into positions of power — a leader in geothermal energy and capable of developing innovative direct air capture technology the United States struggles to build?6

A culture of technology that is about freedom rather than domination, about tangible benefits, not abstract achievement — that’s the kind of culture that could turn Waymos from scary and unknown death traps into the liberating bicycles of the 21st century.

Now, yes, this too is a small magazine, but I put my name on my shit, so I get to feel superior.

I have to point out, inspired by the great philosopher-economist Amartya Sen, that progress or development is not just about GDP. The point of wanting a wealthier society is because wealth enables freedom. Freedom from poverty, from disease, from hunger, from exploitation … But the core goal is freedom! If, in order to make the line go up, you strip away freedoms, then you’ve lost the plot entirely. Even if it were true that granting more freedom to over half the population yielded a reduction in technological progress, it does not then mean that we should reverse that trend.

I took an Uber Pool several years ago where the driver (male) and the two other passengers (also male) began talking loudly and laughing about how strange it was for women to take Uber Pools because someone might rape them. Thanks for looking out, fellas!

Men also become much more supportive — a majority of male respondents in the West actually support autonomous vehicles, while just 35% do in the rest of the country.

This is fine of course! Just… do both.

The actual problem is, of course, localism, excessive proceduralism, and anti-growth politics.

Joe Weisenthal had an interesting Tweet recently, where he observed that most of the rhetoric from the tech industry in recent years is pitched at investors, not users or the general public. This is why we get the grandiose, alienating sci-fi rhetoric. What a (usually male) wealthy tech investor cares about will just be radially different than what ordinary users care about. So you get a lot of rhetoric around AI that frames it as something that will replace people rather than augment them. You get “adapt or die” instead of a sales pitch and trainings designed for regular people. You have rhetoric that almost seems to celebrate artists being replaced.

This is why they’re aping Andreesen rather than MADD rhetorically. They need money from investors more than they want people to use the products more (which, maybe, indicates we’re in a bubble).

This is great! I would argue also that the onus is not just on women and the culture to embrace technology, but also for technology company developers and investors to consider the needs of women. If there's one thing Silicon Valley is great at building, it's the "private taxi for my burrito" type of company - ways to reduce social friction that actually (I think) promote loneliness. I heard the quip somewhere that the prototypical Silicon Valley founder is a bachelor who just wants to replace the things his mom used to do for him (drive him around, bring him food, pick out his clothes). Jessica Winter wrote a great New Yorker piece a decade or so ago, asking 'why hasn't Silicon Valley built a better breast pump' - given how many hours women spend extracting milk, that's a great example of a technology that is long overdue for innovation. Besides getting more women in investor positions, I'm not sure what the solution is, but I feel like there's a ton of untapped potential in tech to build better products for women.