You're being rude. Put away your phone.

New manners for a post-smartphone society

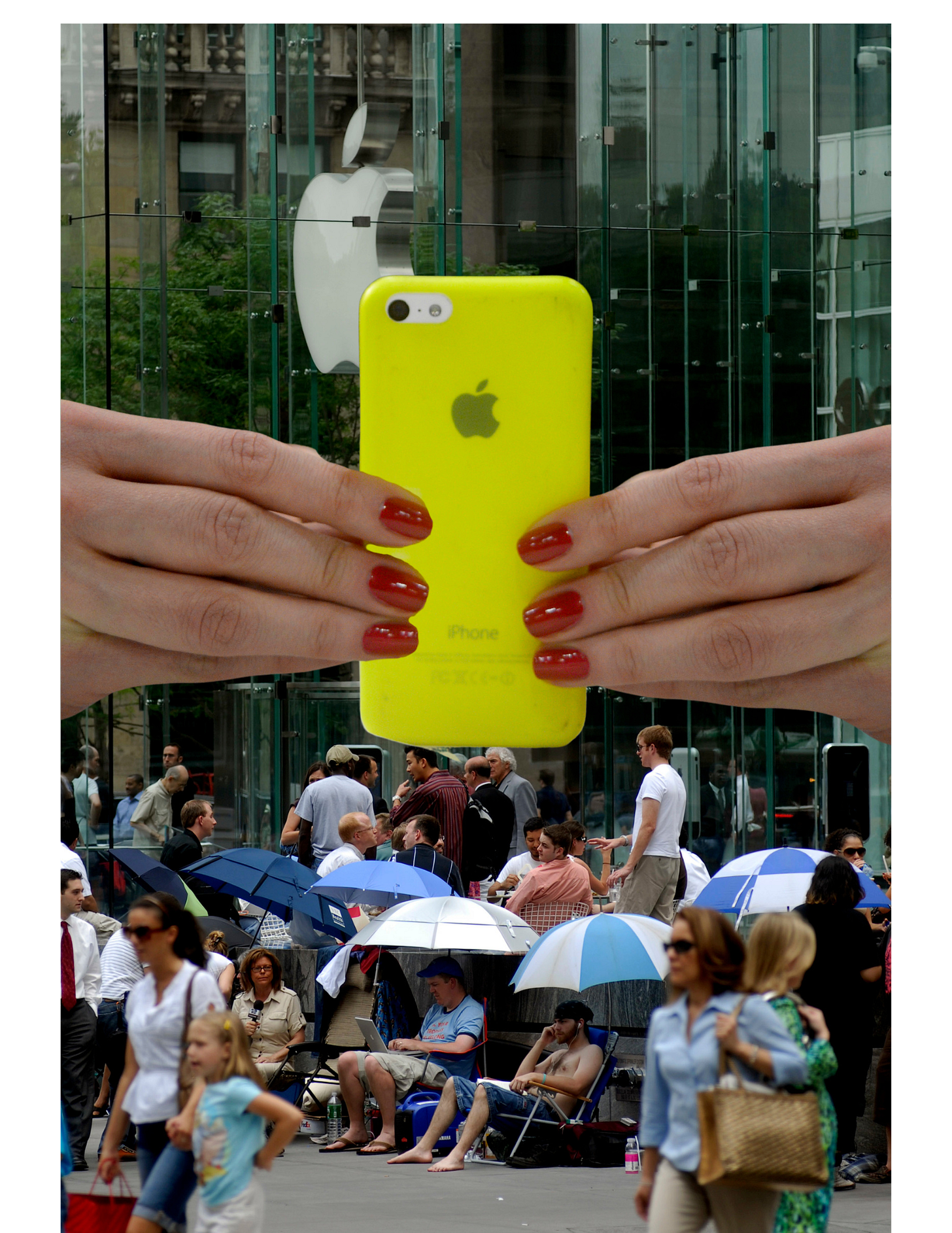

Our current era did not — if we’re being honest with ourselves — begin in 2016 with Brexit or Trump, nor in 2008, with Obama or Lehman Brothers. Rather, it started somewhere around Jan. 9, 2007, when Steve Jobs announced the iPhone.

I remember the day of that keynote. I was an Apple devotee but also a high school student in New Jersey. So I waited anxiously in biology, then English, and then gym — aware that something like an Apple phone was being announced (I had anticipated it for months), but not knowing any particular details. I did not learn what, exactly, had happened until hours later, after school ended, when I scurried to one of the barely chaperoned computers in the corner of the band room and logged on to apple.com.

The speech is famous, iconic, but curiously forgotten. Now it seems strange — in part because Jobs has to work hard to explain what an iPhone even is. Apple, he says, is announcing three products — a phone, a touchscreen iPod, and a “breakthrough internet communications device.” Then the reveal: just one device, the iPhone.

What stands out now, though, is the product demo. In a series of fluid gestures, Jobs starts listening to a track by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, gets a call from another Apple executive, picks up the call, and — while still on the call — goes over to his Photos app, finds and emails a photo to the executive, and then looks at movie tickets.

Of course, much of this was technologically impressive at the time, including the fact that you could do anything without dropping the call. But the point, too, is one about productivity, effectiveness, and the type of life that the iPhone will enable. The message is not only that the iPhone will be useful, but that its interface will enable intentional consideration, decision, and action.

Because you can see, even more clearly with the distance, the theory of attention that underpinned the iPhone: that with these calm and capable devices in our pockets, we would ourselves become calmer and more capable. That we would master what cognitive scientists call executive functioning — the ability to mentally plan, organize our working memory, and achieve our goals. That with these conscientiously designed devices in our pockets, we would ourselves become more conscientious.

And you can see, too, what Jobs is really doing: He is using his phone. He is engaging in the default resting activity that will soon preoccupy Americans in living rooms and elevators, doctors’ offices and toilets. You can see how this idyll of attention became one of the great promises of American business — how it changed millions of lives and birthed dozens of subfields — and how it was completely and totally wrong.

Nearly 20 years have passed since that speech. It is time to take drastic action.

At this point, if you don’t see that phones — and the social internet they enable — are disrupting the basic mechanisms of a thoughtful inner life and a thriving democracy, then I don’t know what to tell you. If you don’t believe me, then that’s fine. I challenge you to read this story on your screen without ever (1) clicking to another tab, (2) switching apps, (3) reaching for another device, or (4) getting up. My bet is you won’t be able to do it.

We are ruled by our phones. The phone sets the pizzicato of Americans’ daily lives — a constant, unignorable mental plucking that sounds at all hours and shapes the substrate of our days. It has bestowed on us an infernal mental itchiness, and it whispers, ceaselessly, to take a break from whatever else we’re doing and look at the phone again.

This is an unacceptable, horrendous way to go through life — and if we’re being honest with ourselves, it has been unacceptable and horrendous for years now. If “how we spend our days is how we spend our lives,” as the slogan goes, then ask yourself: When you bought a smartphone, is this the life you chose?

If we want to escape our current social, political, and even economic mess, then we will need to clean up this attentional Superfund site first. This change is possible — Americans have improved their moral keenness in the past — but it will take an overhaul in our social expectations and habits.

It will take, in short, an in-person revolution. That is, a revolution of in-personness. We need not only to dispense with the phone but to discard the whole way of thinking, living, and remembering that the phone and social media have foisted on us.

First of all, we’re going to need some new rules.

A few new manners for a post-smartphone society

It’s rude to look at your phone when somebody else is talking to you, it’s rude to play videos on your phone in public without headphones, and it’s a little rude to take your phone out at a restaurant, period. (This is one reason that QR code menus are such a scourge.)

We need to start telling people that they’re being rude. We need to codify those expectations in PSAs, TikToks, and advice columns — and then we need to go further. We need new norms, new manners, new courtesies. Perhaps we need to say: You should essentially never take your phone out at a party, at a restaurant, or at a concert. If you need to text your boyfriend, wife, or partner, then step outside or go into the bathroom before pawing at your little screen.

Perhaps we need to say that it is rude — bordering on callous and self-centered — to take your phone out of your pocket or bag if you’re in a room with other people, that it suggests you think that those little icons on the internet you call mutuals are more interesting than the many real and respirating people around you.

Phones are a lot like shoes: they are peerless devices for navigating the physical world beyond one’s front door, they have a lot of brand value, and they can get pretty dirty in the outside world. In civilized households, it’s seen as gross to wear your shoes past the entryway, so people take them off. We should start treating phones the same way. Perhaps we should get landlines again and leave the smartphone by the door.

I also don't want to see your phone out at a party. We need no-phone birthdays and weddings. We need to come up with ways to restrict our own access to phones in social spaces. Phones can be useful cameras — but the thing about cameras is that unless you’re an amateur photographer, only one person in a social setting really needs to be taking photos. So designate someone to be the photographer, and the rest of you put them away.

Yes, you might think that checking email on a vacation is “pretty important.” But pretty soon you’re going to be sitting on a beach, or in the woods, or on a lake somewhere, and instead of enjoying your surroundings, you’re going to be watching Instagram ads for some direct-to-consumer product you had never heard of before and don’t need. No, you do not need a skin tint with patchy SPF, or magnets that make it easier to breathe through your nose.

The fact is that almost nobody can control themselves around the glowing little demon. That’s fine — it doesn’t make you a bad person for failing to do so. But it does make us a bad society for allowing it to happen. The way that we manage temptation as a society is through manners, expectations, and peer pressure.

We need schools and workplaces to experiment with new communal ways to restrict phone access. Schools are already banning smartphones all day in the building — and thank goodness for that. But we need to go further.

How about a screen-free week for adults? How much planning would it take for a household, a neighborhood, or a school to coordinate grocery lists, parent drop-offs, and playdates before a week even starts? How much of that social infrastructure, once built, would pay dividends long after the week was over?

We need adults to experiment with new ways to quiet their phone’s incessant claims on their attention. Smartphone makers should be required to make deleting your web browser easy. There is a new tranche of simplified, so-called “dumbphones” built on the Android system; People should try them out, and Apple should make a dumbphone, too — and bring back the iPod while it’s at it.

We need these rules because we have normalized a level of addiction that requires more than a nicotine patch and some gum to fix. Using a smartphone is like walking into a room and then forgetting why you walked in the door in the first place, every moment of every day, forever.

Even if you picked up the phone to check on a text from your child — or, more likely, to check on your fantasy team — you are going to glance at Instagram while you’re there. Or look at your other text messages. Or mindlessly “tap around” between apps for no other reason than that your brain likes watching colors dance across the screen.

Log off, tune in, go out

More than rules and courtesies and new products, an in-person revolution demands style and panache, vulnerability and good-old togetherness. We need to, at once, embrace and diminish the theater-kidification of everyday life. What I mean is that we need to stop performing — a little bit, all the time, for the internet — while at the same time begin performing for our family and friends who love us, and even for strangers on the street, whose days are brightened by our presence.

We need to have friends over for dinner every Friday or Sunday, and sometimes we need to serve something sort of boring and not-very-Alison Roman-like to those friends. We need to do karaoke and forbid anyone from filming it. We need fancy parties where kids are invited. We need more restaurants with dress codes for gentlemen. We need cookouts for no reason at all. We need to watch sports in sports bars or at our buddy’s house — not alone, not on our phones, but together!

We need to join book clubs, movie clubs, sports leagues, the community theater. We have to go to in-person events for the sole reason that they are happening near us. We should go to the pancake breakfast, the opera, the church service, and the local high school musical. Go to the movies, too.

We need to ditch this ridiculous but hegemonic idea that life can be optimized. We hear it everywhere — from podcasters like Andrew Huberman, from beauty influencers and life-hack bloggers, and even from the interfaces of our devices ourselves, which whisper that some perfect configuration of digital elements will yield the same fluid ease-of-use as a bicycle. It is wrong. We are human beings, after all. And that means we need to dream, to love, to eat, to dance, to climb, to run, to pray, to breathe, and to look into our friends’ eyes — not a moving digital image of their eyes, to be clear, but their actual eyeballs.

This will mean accepting boredom. It will mean, at times, accepting mediocrity — the mediocrity of a club where someone might say something that is less incisive than the best commentary you can find on the internet. That will be OK.

Our little revolution will mean discarding the idea of “interestingness,” at least as we conceive it right now. To escape from our malaise, we have to drop the idea — inherent to social media and really to any digital space where bored eyeballs gather — that if some activity would not interest a national or international audience then it is not worth doing. Virtually all of the best parts of life, after all, would not interest a national or international audience.

There will always be another cookout, party, or bar somewhere else, where something else is happening — and you wouldn’t want to be there, anyway. You’re here.

We need to recognize the wisdom, which almost now passes for an ancient koan, that your future friends are probably the people you see every day. That your life is likely to be changed not by some hyper-optimized romantic or platonic soulmate out somewhere else — in the largest city possible, on the internet somewhere — but by someone who already lives a few blocks over.

An in-person revolution will mean accepting a lot of things. It will mean that — when you feel lonely — you should go out or call a friend, rather than log on or open an app. It will mean staying brittle and lively and open and embodied. It will mean accepting that conversations and meals and even parties have lulls, pauses, and moments when nobody is talking to you — but that you don’t need to open your phone during them. (It is going to be hard for me to unlearn that one.)

This in-person revolution might even be happening near you right now — you probably don’t know it yet, because nobody is posting about it. So loosen up, log off, and go find it.

Show up to volunteer. Go to the local concert where some balding guy will play guitar. Learn a language even though AI will do it better pretty soon. Go to the library and check something weird out, then turn your phone off, hand it to a friend, and read 50 pages.

Watch a TV show with your phone in the other room. Learn to sketch. Wink at strangers. Put a piece of tape over your phone camera. Have another family over and play charades, or sardines, or darts, or gin rummy.

Go outside and just stand around. Make a campfire. Honestly? Smoke a cigarette, if it helps. Log off, tune in, go out. Eventually we’re going to figure out how to live together again. Let’s start now.

I agree with this piece directionally, but it also seems hyperbolic in its description of the current state of affairs. I was at a wedding over the weekend where people pretty much kept off their phones all evening. When I hang out with friends we generally keep the phones in our pockets. Yes occasionally someone will look something up on them if it’s directly relevant to the conversation, but then they go away again.

I find the problem of phone addiction impacts me far less in social situations, and more when I’m trying to complete focused work when I’m alone, whether it’s my literal job or a hobby like reading or drawing.

I won the challenge! (Although I was reading this on my phone when I should be making breakfast.)