Local control is not democracy

Three ballot measures might finally let New York City build. The City Council is panicking.

One of the most important elections happening today has flown entirely under the radar. It’s not Zohran Mamdani and Andrew Cuomo duking it out for New York City’s top job. It’s not the myriad mayoral races or the Virginia governor’s race. It’s not even presidential hopeful California Governor Gavin Newsom’s gerrymandering ballot measure.

No, for my fellow housing wonks, we’re all zeroed in on the bitter fight to wrest local control away from the New York City Council. This fight over process and democratic governance will determine whether any mayor can actually address the city’s acute housing shortage, and it all comes down to two words: local control.1

The practice of “member deference” isn’t actually written into law, but it may as well be. In New York, the City Council has the power to approve or reject new housing projects and zoning changes. But in practice, lawmakers will defer to the local councilmember about matters in their district; everyone wants to make sure they have the power to block development in their nook of the city, so they support their colleagues in doing the same. The effect? An unprecedented housing shortage and a homelessness crisis second only to the Great Depression (really).

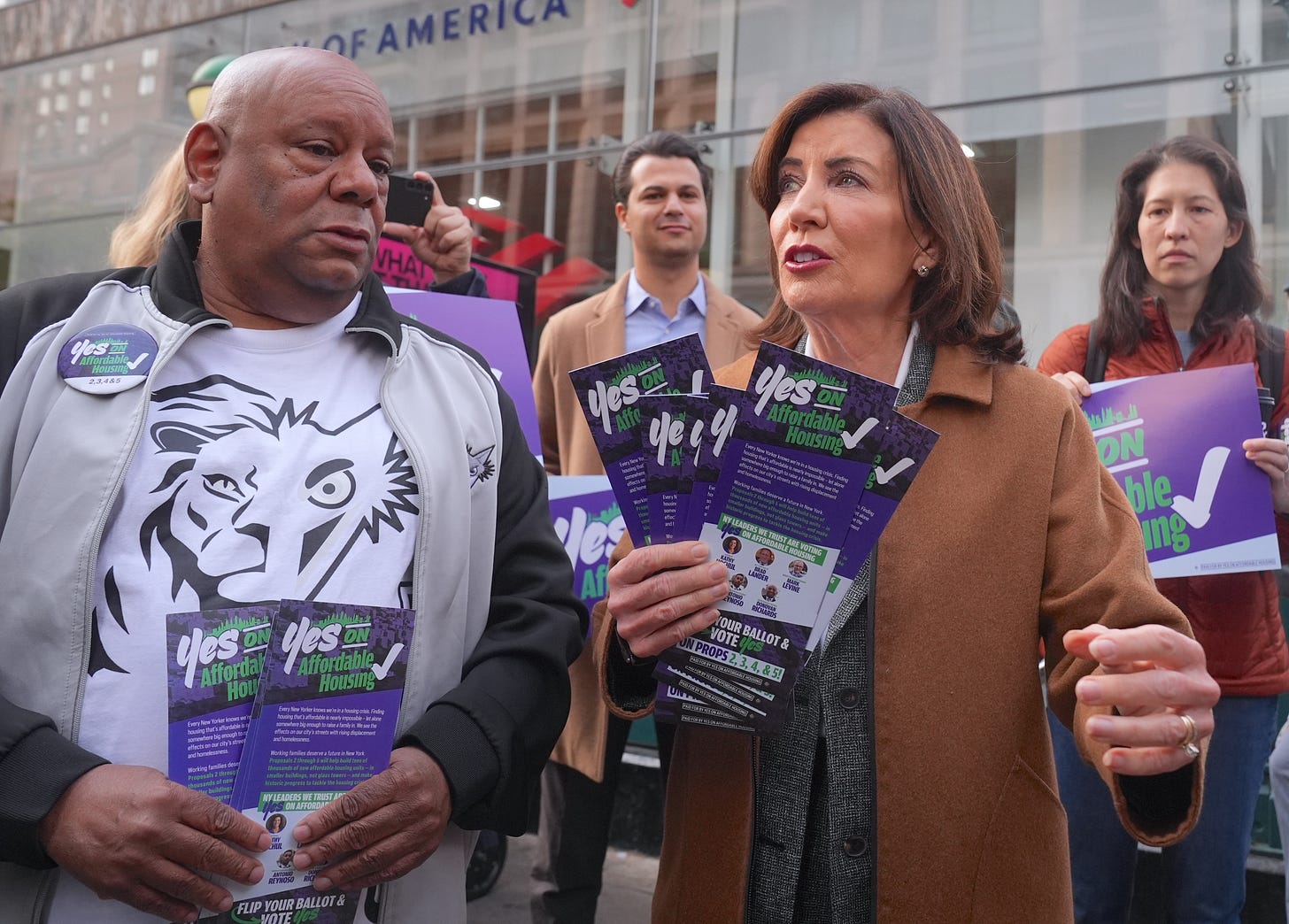

There are three measures relating to housing: questions two, three, and four. They all essentially empower the mayor and administrators within the executive branch while removing discretionary authority from the legislators at City Hall. All of them have the purpose of expediting project approvals for both affordable housing and market-rate housing.

Question two would fast-track affordable housing by letting a board appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the council give it up or down votes, instead of requiring a seven-month review. It also targets the 12 neighborhoods that have produced the least affordable housing.

Question three is also a fast-track measure but this time for small housing projects that need minor zoning changes.

Question four creates a new affordable housing appeals board — consisting of the mayor, the Council speaker, and the relevant borough president — that could overrule the City Council if it opposes an affordable housing development.

The thinking behind these reforms has long been YIMBY gospel: Decentralized, localized power produces less housing because its costs (construction, noise, parking difficulties) are concentrated and its benefits (slower rent growth, faster economic growth) are diffuse. That’s why YIMBY reforms in recent years have sought to move power up to the state level — from California to Montana to Texas and Colorado, pro-housing activists and lawmakers have stripped the authority of local officials to block necessary housing production.

This isn’t just theory. Research has repeatedly shown that decentralized authority leads to fewer houses being built. Economist Evan Mast looked at what happened to housing production when towns increased local control over housing development decisions. He found that this switch reduced the average number of housing units permitted by 21%. For multifamily housing, the effect was nearly 40%.

This week’s ballot measures won’t solve New York City’s housing crisis. But they are necessary preconditions for any mayor serious about eliminating the veto points that block new housing development.

“What it does is it makes a pro-growth political leader possible,” Yale Law professor David Schleicher2 told me. They’re the reforms mayoral favorite Zohran Mamdani will need if he really wants to make good on his promise to build 200,000 new affordable homes. Too bad he hasn’t endorsed them.

The City Council’s hysterical protests against these measures have made their need all the more obvious. Despite calling the ballot measures “undemocratic“ and a “power grab,” the most undemocratic move has been by the City Council itself.

At the end of August, the Council pressured the Board of Elections — whose members are appointed by the Council — to block New Yorkers from being able to vote on the ballot measures in question. The BOE had quite literally never rejected any measure sent before it. The attempt failed, but the desperation has not abated.

In a real tear-jerker of an op-ed, two NYC Council members claimed that removing veto points to affordable housing production amounted to ignoring “critical racial analysis” and the historical injustices done to “Black, Latino and Asian communities” who once lacked power in development decisions.

“Now that we have the most diverse City Council in history, with record representation for women, Black, Latino and Asian New Yorkers while approving record amounts of housing with demanded investments, it should raise alarms that there is an effort to take away this hard fought-for democratic power,” they wrote. “It’s important that we question: who benefits when power that belongs to the people is taken away and placed in the hands of a few? And who is behind this?”

Note that this op-ed does not concern itself with the fastest and best way to address the affordable housing crisis. It is not laser-focused on the outcomes that people actually care about, like reducing homelessness, slowing rent growth, and adding affordable homeownership options. It’s obsessed with process and power.

At its core, the fear these legislators have is that they will no longer be able to extract concessions from developers — concessions that mean fewer units, shorter buildings, and more expensive housing for everyone.

If I’m being generous, it’s possible they genuinely believe that securing some parks and a few more units of affordable housing are worth the wait, increased expense, and diminished housing stock. If they are sincere in believing this, it suggests a failure to grasp even the simplest benefit-cost analysis — yet another proof point that their control over housing approvals must be limited.

To put some firm numbers on it: According to one recent report, since 2022, more than 3,500 homes weren’t built because of Council meddling or developer withdrawal due to opposition. “Notably, every one of these projects was slated to deliver affordable housing.”

Remarkably, 3,500 homes is the conservative estimate — it’s impossible to measure are the countless projects that are never proposed because developers know it’s futile to try. Development is a repeat game and in with discretionary approvals the job of developer is only 50% building houses, the other 50% is sucking up to politicians in the form of legalized bribery3.

Let’s return to the argument that moving development decisions from the discretion of the City Council (who nobody knows and barely anybody voted for) to the mayor (who many people know and many more people will have voted for) is undemocratic.

Democratic power in the United States is diffused among far too many different elected officials and appointed bodies. If the voters approve these ballot measures, they are simply moving power away from one body with representational authority to another. Characterizing this as a power grab is nonsensical. Is the mayor not an elected official? Does the city council believe all decisions by the executive branch to be democratically illegitimate?

If the city council were sincerely interested in improving the democratic representation of their constituents, it might ask itself which officials have had to win more votes, which are more likely to be held accountable by the press and watchdog institutions? Any halfway serious inquiry would arrive at the very ballot measures they are now opposing.

I also take issue with the cynical invocation of racial injustice to try to grasp at power. The point of racial representation is to improve outcomes, it is not an end in and of itself. I don’t think that the 58% of New York City homeless shelter residents that are African-American could care less whether the City Council failing to solve the housing crisis is made up of women, Black people, or straight men.

Remarkably, even on its own terms, the argument doesn’t make sense. The current mayor who is supporting the changes is Black, and the likely future mayor is African-American South Asian.

Is Mamdani a YIMBY? My right-YIMBY friends think I’m a moron for even considering the question, and my left-YIMBY friends are probably getting ready to attend Mamdani watch parties.

The real answer is I genuinely don’t know.

He’s said and done a lot to make me feel excited, like telling The New York Times that he changed his mind about the role of the private market in housing construction:

“I clearly recognize now that there is a very important role to be played, and one that city government must facilitate through the increasing of density around mass transit hubs, the ending of the requirement to build parking lots, as well as the need to up-zone neighborhoods,” he said.

But he failed the first big test. He didn’t endorse these ballot measures, remaining quiet when it was unclear how they would fare. Mamdani is a talented politician, and his silence reflects just how divisive this issue would be to his coalition. But if these measures collapse, it will be that much harder for the likely future mayor to enact his ambitious housing growth policies.

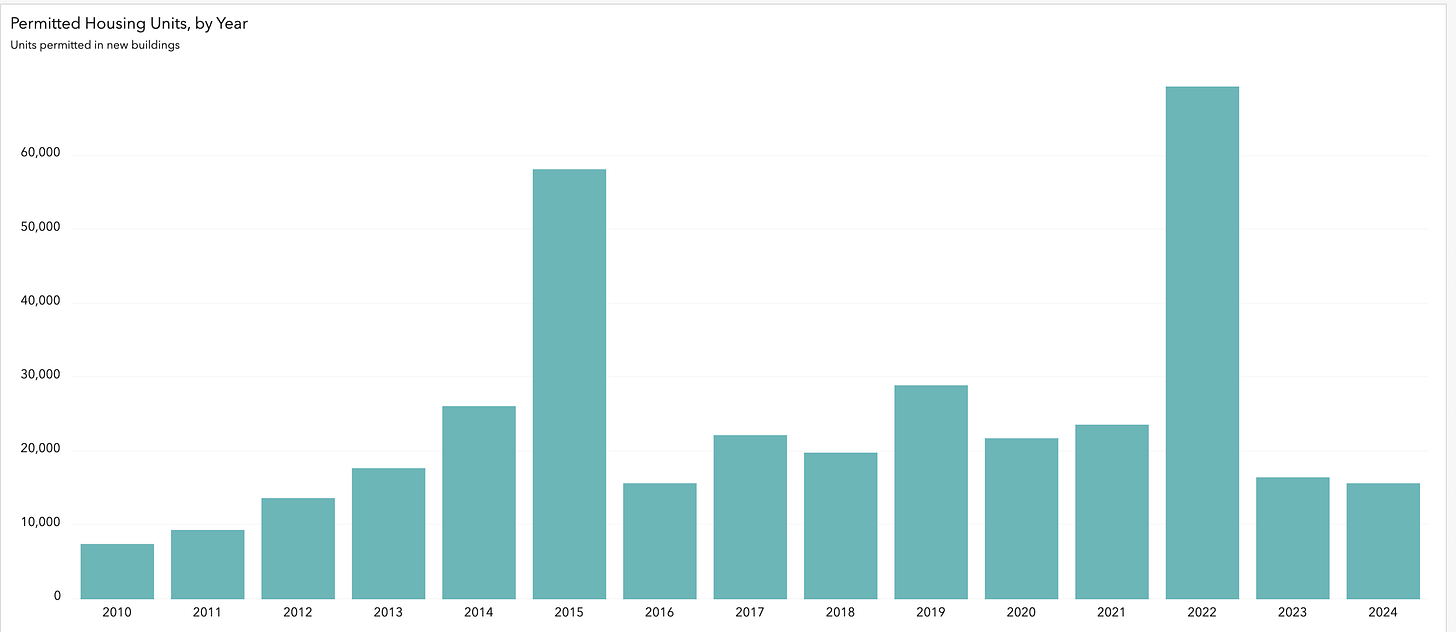

If they succeed, these measures, combined with the Adams administration’s City of Yes zoning reform initiative, could reverse course on decades of sluggish housing growth.

Mamdani is poised to be a great YIMBY mayor or our greatest disappointment.

Update: Shortly after publication, Zohran Mamdani endorsed the housing ballot measures on his way in to vote. He was kinder to the City Council than I was.

The second-most important election for YIMBYs is the New Jersey governor’s race, which features — to my knowledge — the first full-throated, statewide anti-YIMBY campaign of the modern era. Sherrill is polling ahead of Ciattarelli, but it’s a close race and a Republican victory would not just be a bad sign for Democrats nationwide but a bad sign for the politics of housing in the Northeast.

One of Republican Jack Ciattarelli’s ads features his opponent, Democrat Mikie Sherrill, saying “We’ve gotta build more houses” layered over terrifying music and images of bulldozers and housing construction. If the message wasn’t clear enough, it is interspliced with images of dead deer on the side of the road and the sounds of flies buzzing around them. Very subtle.

The ad ends with the words “Stop overdevelopment. Stop Mikie Sherrill. Save New Jersey.”

And it’s not just the ads: During his opening statement in the gubernatorial debate, Ciattarelli mentioned the hits (affordability, education, public safety) but he also added … overdevelopment, arguing that it was taking “the Garden out of the Garden state.”

What’s funny is that Sherrill isn’t really running a YIMBY campaign. Yes, she said New Jersey has a housing shortage, but her proposals are extremely modest.

Schleicher wrote the seminal article on this problem, “City Unplanning” in 2013.

Let’s not forget where Donald Trump got his start…

Good post! I think though that "is Mamdani a YIMBY?" is asking the wrong question. YIMBY is unlikely to be the type of movement to directly hold power. YIMBY ideas aren't popular in that way. What's going on with Mamdani is IMO what YIMBY victory looks like - politicians taking up the most workable ideas out of enlightened self-interest. Mamdani wants to make housing more affordable, and YIMBY has enough pull at this point that it was natural for him to incorporate some of our ideas alongside more traditional leftist ideas.

Mamdani votes in favor of ballot proposals 1-5. Good! But disappointing he waited so long to make that public

https://www.cityandstateny.com/politics/2025/11/how-mamdani-voted-ballot-proposals/409281/