The postliberal war on economics

Peak oil panic didn’t just mislead environmentalists, it helped birth a right-wing anti-markets worldview that is helping run the country

In 2007, a prominent conservative academic predicted civilization would collapse within months. The culprit: peak oil. The collapse never came but the philosophy he built around it—postliberalism—is now in the White House.

The growing influence of postliberals is undeniable, but liberals on the left and right seem taken aback, confused about an ideology that marries extreme social conservatism with a hostility to mainstream economics, the latter a conventionally left-wing position.

In recent years, a large focus of my work was explaining how the 1619 Project made big, provocative claims about the nation’s founding and was forced to backpedal once actual historians began checking the receipts. I find myself again in a similar role as I engage with the postliberal right.

This is a series that will help liberals understand this Frankenstein ideology and where its weak points are. This first installment will focus on the postliberal right’s war on economics.

The postliberals’ master explanation for why everything feels off is to blame free markets, libertarianism, liberalism, “neoliberalism,” or even just plain economics. To hear them tell it, everything is the fault of liberalism: declining birth rates, fentanyl addiction, family breakdown, environmental degradation, cultural decay, illegal immigration, the 2008 to 2009 financial crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, a reported wave of angry, listless young men … the list goes on.

But postliberalism’s critique of economics is intellectually shallow — its proponents don’t understand the discipline they attack, and their anti-market philosophy originated in a failed prediction that they’ve quietly abandoned while keeping the grievances.

Fifty years ago, writing in a private letter, the liberal philosopher Karl Popper expressed shock at the growing power of Marxist critical theorists in the academy: “I feel as if the lunatics were speaking,” he wrote. The claims emerging from the “crits,” as they became known, amounted to “trivial or tautological or sheer pretentious nonsense,” and yet they were being touted as epistemic breakthroughs at the forefront of philosophy.

I must confess a similar sentiment from my own first encounters with “postliberalism.”

I stumbled upon it by happenstance at the tail end of graduate school, about 15 years ago at George Mason University in Virginia, although at the time, it might not have even possessed its current moniker. I was listening in the back of the room while a visiting scholar from another university workshopped a paper about 18th-century political thought. Patrick Deneen, a political theorist from neighboring Georgetown University, dropped by as one of the faculty discussants.

Deneen’s questions to the presenter morphed into his own dissertation about the social corruption allegedly caused by free market ideology. I was used to this sort of argument from the anti-capitalist left, but this was something different.

Deneen seemed to view capitalism, and indeed all of modernity, as a rebellion against an earlier era, ordered around an idiosyncratic vision of a moral “common good.” Free markets and individualism, he suggested, had lured modernity into a culture that lived and consumed beyond the “natural” constraints of the Earth’s finite resources.

I thought little more of Deneen’s claims for years to come until he resurfaced at Notre Dame in 2018 with the publication of Why Liberalism Failed, a sweeping philosophical treatise that has since become the bible of the postliberal movement. The book broke into mainstream media, picked up a provocative blurb from former president Barack Obama, and secured Deneen a spot on the conservative campus speaking circuit. It also contained many of the arguments he sprinkled through his seminar comments, presentations, and blog posts in the late 2000s — just in longer form.

The book’s thesis held that both progressive and classical versions of liberalism have eroded the ancient and communitarian dimensions of society — family, religion, culture — by prioritizing individual autonomy and economic growth. Over time, a society’s community and culture become degraded by the uninhibited forces of consumption-driven individualism.

Postliberalism is at its most persuasive at its most abstract. When you force proponents to engage in specifics, the facade falls apart. Before he learned to remain abstract, Deneen centered his burgeoning ideology on a very specific empirical prediction: that modern life was about to hit a physical limit. A mid-2000s panic over energy scarcity seemed like proof that liberalism was going to fail at its central promise: economic prosperity.

The failed prediction at the root of “postliberal economics”

After being denied tenure at Princeton in 2004, Deneen’s scholarly attention shifted away from theorizing about the nature of democracy and toward more tangible and immediate issues of societal crisis. Environmental “apocalypse,” as he styled it, ranked foremost among these concerns, albeit from a perspective that emphasized the Earth’s conservation as a quintessential “conservative” value.

In a 2007 blog post, Deneen predicted an impending societal collapse from environmental degradation, noting “in all likelihood we’ll experience some severe civilizational dislocation in coming months and years as a result of peak oil.”

Peak Oil Theory was a trendy doctrine from the 2000s that foresaw an imminent natural resource depletion, whereupon fossil fuel energy production would enter into a rapid and irreversible decline. Widespread shortages and economic collapse would soon follow as our oil-dependent economy could no longer sustain consumption at current levels.

It has since fallen by the wayside among environmentalists as new fossil fuel exploration and better extraction technologies vastly expanded the world’s estimated oil reserves. Green activists today have shifted their arguments to emphasize climate change as their leading concern, even arguing for intentional fossil fuel sequestration on the grounds that the Earth’s atmosphere cannot handle the emissions that would arise from currently known oil reserves.

But for Deneen, the snapshot claims of late 2000s Peak Oil Theory provided the “eureka” moment that led him to develop postliberalism. He recounted this much on his blog:

[W]hen I learned about “peak oil” - that is, the imminent depletion of roughly half the world’s oil reserves, and by far the easiest accessible and cheapest stuff - it finally made sense to me why a political philosophy that I had long held to be fundamentally false - modern liberalism - nevertheless had prospered for roughly the past 100 years and had gone into hyper-drive over the past half-century.

Modern liberalism - the philosophy premised upon a belief in individual autonomy, one that rejected the centrality of culture and tradition, that eschewed the goal or aim of cultivation toward the good established by dint of (human) nature itself, that regarded all groups and communities as arbitrarily formed and therefore alterable at will, that emphasized the primacy of economic growth as a precondition of the good society and upon that base developed a theory of progress (material as well as moral), and one that valorized the human will itself as the source of sufficient justification for the human mastery of nature, including human nature (e.g., biotechnological improvement of the species) - is against nature, and therefore ought not to have “worked.”

In this telling, the posited resource limitations of Peak Oil Theory revealed not just the source of the coming environmental disaster, but its culpable party, which is to say liberalism — and specifically economic liberalism — itself.

The explosion of economic prosperity from the 18th-century stirrings of the Industrial Revolution to the present day depended upon fossil fuel in the literal sense. In Deneen’s reasoning, that fuel came from a limited resource that would soon be depleted. The Great Enrichment of the modern era, and indeed humanity’s escape from the multi-thousand-year Malthusian Trap of hunger and stagnation, only came about through artificial means that elevated humanity’s economic consumption beyond its “natural” state.

Modernity borrowed from the planet’s future to give itself material comforts. Liberalism functioned as a rationalizing ethos for this resource extraction, but with it came a cultural degradation that supposedly eroded ancient social bonds of family and community. And the entire liberal economic façade, Deneen predicted, would soon come crashing down as nature’s hard constraint of Peak Oil enforced itself upon a society under the spell of rapacious libertarian prophets of consumption.

Except the Peak Oil-induced collapse, said to be only months away in 2007, never happened.

When the prophecy failed

Deneen quietly abandoned Peak Oil Theory, and with it a draft academic paper entitled “Peak Oil and Political Theory: The End of Modernity?” that he presented at several conferences in the late 2000s. He simply swapped in a different set of crises rooted in less tangible claims about an accelerating cultural collapse.

By 2021, he had found another target by turning his sights on the American Founding itself. “We must see this jointly created, invented tradition of America as a fundamentally or solely liberal nation as a recent innovation,” he declared in a keynote address at the National Conservatism conference. Using language lightly cribbed from his Peak Oil musings a decade earlier, Deneen denounced the individualist, free-market, and liberty-minded legacy of 1776 as “an invented tradition that has been launched in the service of a rapacious ruling class.”

No matter the occasion of the problem, free markets and economic libertarians were somehow always its underlying cause.

Deneen clearly believed that he had exposed a foundational flaw in “liberal” modernity, and with it, the entire field of economics. What economists see as “wealth,” Deneen thought, was better described as an “accelerated use of nature’s bounty” — a “self-delusion” of the “faith-based adherents of modern economics” and an addiction to what he dubbed a “consumptive growth economy.”

But Deneen’s arguments came across as bumbling aesthetic grievances, offered from a perch that neither understood economics at a basic level nor showed any interest in investigating it beyond the list of caricatures he had settled upon.

Anti-modernity right-wingers are nothing new. Deneen’s thesis reminds me of the 19th-century Scottish reactionary Thomas Carlyle, who raged against the “laws of supply and demand” for flooding the world with “cheap and nasty” goods, thereby upending the hierarchies of an earlier social order through an overextension of present-day luxury.

The real objection of Carlyle, and Deneen after him, came from a bristling revulsion at modernity itself. In an earlier century, Carlyle dubbed this liberal paradigm eleutheromania, a frantic and unnatural zeal for freedom.

Amid the current “crisis” of individualistic excess, postliberalism has emerged as a corrective response to reorient society to its “natural” course, rooted in a nebulously defined concept of the “common good” that looks suspiciously similar to Deneen’s own personal aesthetic and cultural preferences.

Of course, when “virtue” and the “common good” become stand-in terms for one’s own personal political aesthetic, any deviation from that position also becomes a rebellion against “the good” and even “nature” itself.

Trumpism is proving postliberal economics wrong

The core postliberal economic argument is this: Markets are powerful allocative mechanisms, but they also reshape social life in ways that erode nonmarket goods (family stability, community cohesion, cultural continuity). Economists systematically underweight these costs because they’re hard to measure, and libertarian ideology provides ideological cover for ignoring them.

The market isn’t just allocating goods; it’s reorganizing society around consumption, mobility, and price, and that reorganization is destroying families and society’s fundamental social fabric. In their view, a relentless focus on efficiency, output, and maximizing consumer surplus and shareholder value produces predictable side effects: deindustrialization, dependence on fragile supply chains, weaker labor bargaining power, and a fractured common culture.

So, they pitch the opposite: a producer’s economy over a consumer’s with higher wages, stable work, more domestic production, tariffs and protectionism, a large social safety net (albeit one structured to promote traditional family roles and values), and a tolerance for inefficiency and higher prices. Liberalism says individuals should be free to move to where they are happiest and workers and firms to where they are most productive; postliberalism says the state should direct individuals, workers, and firms toward a “common good.”

Of course, disagreement over what that common good entails is entirely why liberalism exists in the first place.

For all their grousing about economics, most postliberals do not understand the discipline. Nor do they exhibit any interest in educating themselves about what mainstream economists do, to say nothing of the field’s free market subset. In reality, from trade imbalances to deindustrialization, the problems postliberals lay at the feet of liberals, libertarians, and economists are caused by unrelated factors and would worsen if their preferred policy regime was in place.

Postliberals invoke the United States’ “trade deficit” as the central economic problem of our age, although most would be hard-pressed to explain where it fits in the Balance of Payments identity at the center of international accounting.

They will make sweeping empirical claims about the decline of American manufacturing since the 1970s without bothering to check whether the data even supports this contention (it doesn’t).

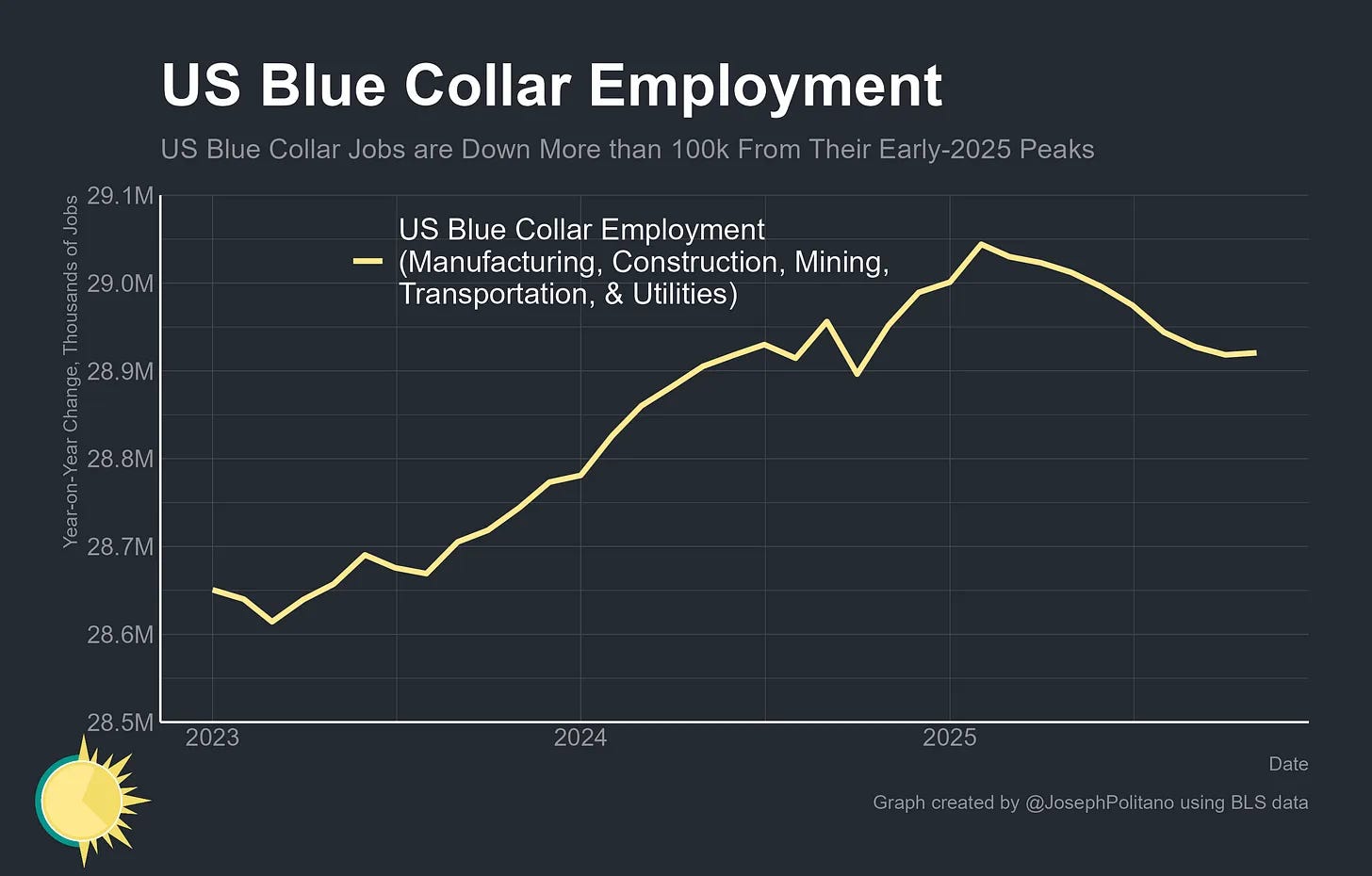

They contend that the United States faces a manufacturing jobs crisis, remaining oblivious to data showing more manufacturing job openings today than 20 years ago. President Trump has provided a protectionist economic shock through his tariff policy and blue collar jobs have simultaneously declined.

The truth is, Trump’s economic record is proving the postliberals wrong on their own terms. But the attraction to fringe economic thinking remains deeply rooted.

Amid its push to excise mainstream economics from the discussion, postliberalism supplants it with a hodgepodge of heterodox economic crankery. Many postliberal economic takes come from the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs, a state-funded outfit of the Viktor Orban government. It’s run by Gladden Pappin, an academic expatriate from the United States who coedits the postliberal journal American Affairs and is one of the movement’s primary activists along with Deneen.

Pappin has provided a string of jobs to postliberal economists who blend extreme social conservatism with their own peculiar adaptations of Modern Monetary Theory, the fringe doctrine that helped to spawn the inflationary crisis of the Biden years. Orban appears to have acted on some of this advice by imposing price controls in a futile bid to stem the worst inflation rate in the 27-member European Union.

When bad history becomes a permission slip for bad policy

Postliberals attempt to ground their economic thinking in American history, pointing to the “American System” school of Henry Clay, an early 19th-century senator who espoused a tripartite scheme of tariffs, infrastructure subsidies, and central bank financing to steer the American economy in the direction of autarkic self-sufficiency. Several articles at the postliberal journal American Affairs identified Clay’s model as an augmentation and continuation of Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 tariff system and thus the true “conservative economics” of the United States.

This characterization is meant to contrast with the British interlopers who allegedly invented “laissez-faire” theory and free trade to ensure the nascent United States’ subservience to their economic empire in the 19th century. Some postliberals even go so far as to depict themselves as recovering the “lost” economic wisdom of our “American System” past.

Deneen, for example, declared that Hamiltonian economics “has been forgotten especially by today’s libertarian cheerleaders of free-market globalism.” Pappin also calls himself a Hamiltonian, urging “a developmentalist revival” of this allegedly forgotten tradition to combat the free-market libertarians. Others point to the tariff system of the Gilded Age as proof that the “American System” works in practice.

There’s a problem with this narrative though. Free-market economists have been engaging with Hamilton’s and Clay’s arguments since the moment the ink dried on their original articulations.

The record is conclusive. The “American System” performed poorly when attempted in the 19th century and culminated in a spectacular backfire in 1930, when Congress adopted the Clay-inspired Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act in an attempt to insulate the country from the 1929 stock market crash. Following the crash, Congress rushed through a pending tariff bill that aimed to “protect” American producers from the economic turmoil. It failed, collapsing global trade and plunging the world deeper into the Great Depression.

Despite their “American” moniker, these interventionist ideas also drew explicit rebukes from James Madison and Thomas Jefferson at the end of their lives. Clay’s tariff system supercharged the culture of lobbying in the early republic, giving rise to the political corruption that came to define the Gilded Age by the century’s end.

And the best empirical evidence from economic historians illustrates that high protective tariffs likely hindered American economic development in the late 19th century when compared to a free trade alternative. Far from rediscovering a “lost” chapter of American economic history, Deneen, Pappin, and their postliberal colleagues simply do not know or understand this scholarly literature (or worse, they do not care because their real goal has nothing to do with economic prosperity and everything to do with installing the social-cultural regime of their liking, no matter how much it costs).

Despite operating well out of their depth on economic matters, most postliberals write as if they have exposed some devastating truth about the discipline — if only someone would listen. The situation is akin to the astrologer who chastises NASA for ignoring horoscope advice in advance of space launches, while also promising to lead the space agency’s course to Mars if only their fellow astrologers could be given a seat at the rocket scientists’ table. And with the “Tariff Man” Donald Trump in the White House, the economic astrologers finally found their coveted seat.

It’s particularly revealing that libertarians, rather than the left, have become the primary intellectual scapegoat of the postliberal scene. “Save America — Reject Libertarianism” railed Sohrab Ahmari in a 2021 blog post for the Claremont Institute, a California-based think tank that has become a hotbed of postliberal commentary in recent years.

According to their charge, libertarians foster an “illusion of neutrality” for the state in the public sphere. This, in turn, somehow caused the cancel culture epidemic of wokeism, the leftward political tilt of Big Tech, and a progressive-left understanding of American history to become “enshrined as public dogma.”

Ahmari doesn’t explain the underlying mechanism, but piecing together his argument for him, he seems to believe that the left is willing to wield state power in service of wokeness, so the right’s failure to respond in kind amounts to unilaterally disarming itself.

Looking back at this argument in 2026, it’s hard to believe the left’s strategy is one to emulate, even if it were desirable. Of course, using state power to force minoritarian views on society backfired on the left. Voters delivered a harsh judgment against woke overreach in the 2024 election, even settling on the widely unpopular Donald Trump as a faute de mieux alternative. If only the right would learn this point instead of seeking to repeat the mistakes of their opponents.

Nonetheless, postliberals have convinced a portion of the American right of their story.

JD Vance, for example, described his conversion to Trumpism at the 2019 American Conservative gala by crediting the president for “explicitly attacking the libertarian consensus that I think had animated much of Republican economic thinking.” No other candidate, he claimed, had been willing to confront this alleged source of Vance’s social grievances. Vance is personal friends with Deneen and Pappin, and he has credited both for guiding him on his own conversion to the postliberal movement.

Postliberals are now in a position to test their theories. If they’re wrong — as the historical and developing modern record suggests — Americans will pay higher prices for the privilege of watching a tiny minority view of the “common good” fail to materialize. The economists they’ve spent two decades scapegoating will be the least of their problems.

More on postliberalism:

The fox in liberalism’s henhouse

There are many open, full-frontal assaults on liberalism. Conservatives, fascists, and communists have all attacked different aspects of liberal values to different ends — from free markets to individual rights to freedom of expression to democratic self-government. In the postwar era, liberalism came out on top. But there are no permanent victories.

How do we live with each other?

Almost exactly 70 years ago, in the first issue of a very different magazine — National Review — founder William F. Buckley proffered his classic definition of conservatism: It “stands athwart history, yelling Stop.”

Discussing right of center post-liberal economics without discussing American Compass is a little weird? Like, no one is out here claiming that Deneen's the go-to-source for post-liberal economics. Not that interesting to dunk on his views there, he's just such an easy target that this ends up feeling like a puff piece.

A more interesting article from an historian like Phil would have been to start with Gary Gerstle's framing that we're coming out of the neoliberal political order and ask what that means for left of center economic policy. For example, should liberal democrats continue supporting tariffs on China, or strict I9 enforcement and mandatory e-verify? If not, why not? Can liberals come up with a "worker-centered" economic, trade, and immigration policy that isn't just rehashed neoliberalism? The Abundance Agenda, for all it's virtues, is definitely not a self-consciously worker-centered program. They'd happily accept cheap labor and material imports from China and Latin America if it meant we could get more high speed rail, houses, solar energy, cheap medical assistants, etc. Americans might want those things, but the upper quintile is the only group that wants them more than they want to protect blue collar jobs.

If we look back in party history to the 80's and early 90's, the group that Henry Tonks calls the "new liberals" were actually explicitly interested in doing protectionist, state-sponsored industrial policy in order to compete with Japan. When Japan's economy crashed, this interest dried up and they resumed status quo governance. But here we are 30 years later post-realignment and the right has taken over both that platform, and its constituents.

We liberal democrats need a better response to the right-of-center post-liberal's arguments, but I'm sorry, this uncharitable dunking just ain't it. Phil's three paragraphs characterizing the post-liberal argument are accurate enough, but he doesn't really engage with the argument on its own terms. It's a good piece, but we need to keep exploring this line more rigorously and charitably. The story is too interesting and influential to treat this dismissively — that'll only backfire.

Great piece but I think it fails to take seriously sources of real, cross-ideological dissatisfaction with modern life. In my view, much of this dissatisfaction comes from the incredible proliferation of addictive technologies/opportunities in America, which are not unrelated to liberalism and capitalism. If retreating from liberalism isn’t the answer (and I agree it’s not) then what can political leaders offer?