We absolutely do know that Waymos are safer than human drivers

What Bloomberg got very wrong about self-driving cars

The Argument readers are invited to a conversation between Jerusalem Demsas and Brink Lindsey, senior vice president at the Niskanen Center, about his new book, The Permanent Problem, on Wednesday, Jan. 21, from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg Center.

America’s abundance movement has focused on regulatory reform and housing policy — necessary fights, but perhaps insufficient ones. This conversation will explore the deeper diagnosis offered in The Permanent Problem: that our crisis isn’t just one of scarcity but of meaning.

Join us for a conversation about why the abundance movement may need to expand its ambitions: from making things affordable to rebuilding the communities and shared purposes that make abundance worth having.

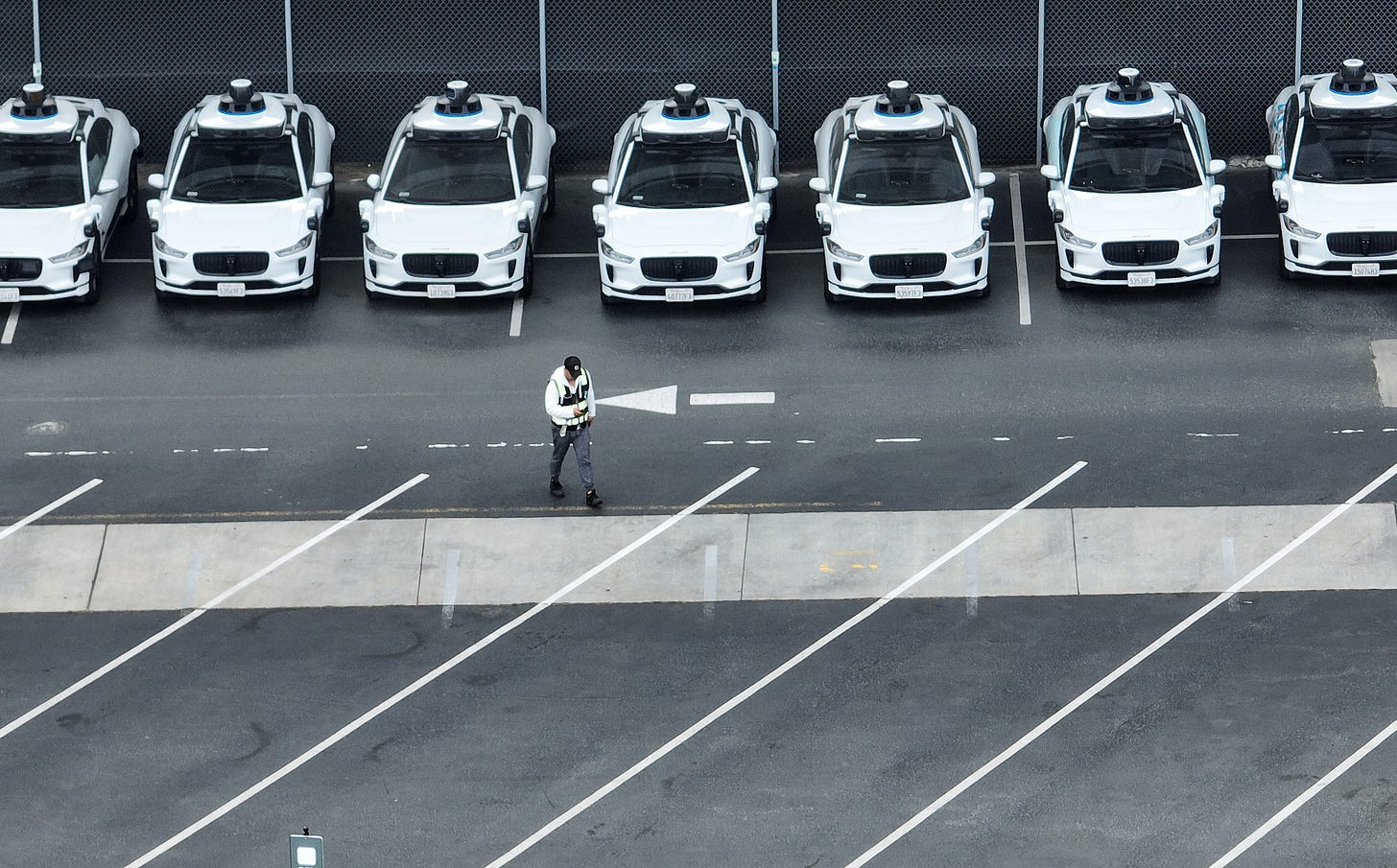

In a recent article in Bloomberg, David Zipper argued that “We Still Don’t Know if Robotaxis Are Safer Than Human Drivers.” Big if true! In fact, I’d been under the impression that Waymos are not only safer than humans, the evidence to date suggests that they are staggeringly safer, with somewhere between an 80% to 90% lower risk of serious crashes.

“We don’t know” sounds like a modest claim, but in this case, where it refers to something that we do in fact know about an effect size that is extremely large, it’s a really big claim.

It’s also completely wrong. The article drags its audience into the author’s preferred state of epistemic helplessness by dancing around the data rather than explaining it. And Zipper got many of the numbers wrong; in some cases, I suspect, as a consequence of a math error.

There are things we still don’t know about Waymo crashes. But we know far, far more than Zipper pretends. I want to go through his full argument and make it clear why that’s the case.

In many places, Zipper’s piece relied entirely on equivocation between “robotaxis” — that is, any self-driving car — and Waymos. Obviously, not all autonomous vehicle startups are doing a good job. Most of them have nowhere near the mileage on the road to say confidently how well they work.

But fortunately, no city official has to decide whether to allow “robotaxis” in full generality. Instead, the decision cities actually have to make is whether to allow or disallow Waymo, in particular.

Fortunately, there is a lot of data available about Waymo, in particular. If the thing you want to do is to help policymakers make good decisions, you would want to discuss the safety record of Waymos, the specific cars that the policymakers are considering allowing on their roads.1

Imagine someone writing “we don’t know if airplanes are safe — some people say that crashes are extremely rare, and others say that crashes happen every week.” And when you investigate this claim further, you learn that what’s going on is that commercial aviation crashes are extremely rare, while general aviation crashes — small personal planes, including ones you can build in your garage — are quite common.

It’s good to know that the plane that you built in your garage is quite dangerous. It would still be extremely irresponsible to present an issue with a one-engine Cessna as an issue with the Boeing 737 and write “we don’t know whether airplanes are safe — the aviation industry insists they are, but my cousin’s plane crashed just three months ago.”

The safety gap between, for example, Cruise2 and Waymo is not as large as the safety gap between commercial and general aviation, but collapsing them into a single category sows confusion and moves the conversation away from the decision policymakers actually face: Should they allow Waymo in their cities?

Zipper’s first specific argument against the safety of self-driving cars is that while they do make safer decisions than humans in many contexts, “self-driven cars make mistakes that humans would not, such as plowing into floodwater3 or driving through an active crime scene where police have their guns drawn.” The obvious next question is: Which of these happens more frequently? How does the rate of self-driving cars doing something dangerous a human wouldn’t compare to the rate of doing something safe a human wouldn’t?

This obvious question went unasked because the answer would make the rest of Bloomberg’s piece pointless. As I’ll explain below, Waymo’s self-driving cars put people in harm’s way something like 80% to 90% less often than humans for a wide range of possible ways of measuring “harm’s way.”

The “we don’t know” argument relies on indifference to the numbers: sometimes they’re better, sometimes they’re worse; therefore it is impossible to say whether, on the whole, they are better or worse.

We do have data on Waymo crash rates

Zipper acknowledged that data on Waymo operations suggested they are about 10 times less likely to seriously injure someone than a human driver, but he then suggested that this data could be somehow misleading: “It looks like the numbers are very good and promising,” he cited one expert, Henry Liu, as saying. “But I haven’t seen any unbiased, transparent analysis on autonomous vehicle safety. We don’t have the raw data.”

I was confused by this. Every single serious incident that Waymos are involved in must be reported. You can download all of the raw data yourself here (search “Download data”). The team at Understanding AI regularly goes through and reviews the Waymo safety reports to check whether the accidents are appropriately classified — and they have occasionally found errors in those reports, so I know they’re looking closely. I reached out to Timothy Lee at Understanding AI to ask if there was anything that could be characterized as “raw data” that Waymo wasn’t releasing — any key information we would like to have and didn’t.

“There is nothing obvious that I think they ought to be releasing for these crash statistics that they are not,” he told me.

How worried should we be, I asked, that Waymo is doing these analyses themselves rather than third-party evaluators? He agreed that it would be better if third-party evaluators did some of these analyses that so far have been done only by Waymo researchers — for example, classifying human crashes in San Francisco in order to enable a direct comparison to Waymo crashes.

But, he pointed out, the data is available for them to do so: “It’d be more credible if it didn’t come from Waymo, but no one else has picked up the baton.”

I kept pressing. Is Waymo being only as transparent as the law requires? Nope, Lee said: “Waymo I think would legally be allowed to be a lot less transparent and is clearly more transparent than Tesla.”

Doing the math

I’ve asserted throughout this piece that Waymos seem to have a “serious injury per mile driven” rate that is about one-tenth that of human drivers. The most straightforward way to measure this is to look at 1) how many miles Waymo has driven (as of their last update, in September, that was 127 million miles; as they’ve been massively expanding their fleet since then, my best guess is that they’ve now passed 200 million miles, but we’ll set that aside for a moment) and 2) how many serious incidents there have been.

Here are some ways you might measure serious incidents: “any police-reported crash,” “any crash where any injury is reported,” “any insurance claim related to property damage or bodily injury,” or “any crash where an airbag deploys in any involved vehicle.” You might also look at “any crash where an airbag deploys in the Waymo” or “any crash where a serious injury or death occurs.”

None of these are perfect metrics, but many of the ways they are imperfect work against Waymo. For example, crashes with a Waymo get reported to police and insurance more reliably than minor crashes between human drivers.

These metrics give slightly different numbers for how much safer a Waymo is than a human driver. Waymos are about one-fifth as likely per mile to report any injury, but half as likely to report any crash — probably partially because minor crashes with human drivers often aren’t reported to the police if no one is injured. According to the published statistics, Waymos are around one-fifth as likely to have an airbag deploy and one-tenth as likely to be in a crash in which there’s a serious injury.

One of the experts that Zipper quoted pointed out that Waymo’s injury rates might be artificially lower since sometimes the car is empty (if it gets into a crash, no one can possibly get injured). But the airbag deployment metric shouldn’t be vulnerable to this — Waymo airbags can deploy in a serious crash even if the car is empty — and is basically in line with the other metrics.

After asking around about how this would be the case, the answer I found the most satisfying was this: Most serious injuries on city streets are suffered by pedestrians or motorcyclists, so whether the car is empty affects serious injury rates less than you might think.

Liu pointed out that Waymo drives on city streets, for which the appropriate comparison is human driving on city streets rather than the human national average. This is true, but it makes Waymo look better, because the San Francisco city streets for which we have lots of Waymo data are, in fact, notably more dangerous than the national average.

Death in Waymo car accidents is incredibly rare. There have been two incidents in which a Waymo was present and a death occurred. I say “two incidents in which a Waymo was present” because in neither of them was it clear that the Waymo actually had anything to do with the death. In one incident, a Waymo was in a line of cars stopped at a traffic light when a speeding driver barreled into the line of cars. A passenger in one of the other cars that was hit died.

In the other incident, a Waymo was rear-ended by a motorcyclist. The motorcyclist was then hit and killed by a different car.

Because death is so rare, it would be bad statistical practice to try to infer Waymo’s safety record primarily from these deaths. Instead, the standard statistical practice when an endpoint is extremely rare is to pick a far more common and far more easily studied endpoint.

If Waymos are far less likely to cause injuries of any kind, far less likely to cause serious injuries, and far less likely to have an airbag deploy, then it is reasonable to conclude that they are much safer than human drivers — even though deaths are far too statistically sparse to say much about.

That was not Zipper’s approach. Instead, he blended two different methods of accounting for death in a confusing way that makes Waymo fatalities look twice as common as they really are.

To understand the math, let’s imagine a simplified situation where there are two cars, each of which drives for 100,000 miles before they collide, killing one person. There are two statistics you could use to describe this situation: One is by looking at the whole population and looking at vehicle miles traveled per death — which is clearly 200,000 miles for each death. Another is by looking at individual vehicles’ travel per involvement with a fatal crash. Each vehicle travels 100,000 miles per involvement in a fatal crash.

When measuring how dangerous human drivers are, Zipper used the first approach, citing data that says that for every 100 million 100,000 miles driven (by any vehicle), there are 1.26 fatalities. He then misread that data and concluded that it means human drivers drive 123 million miles for each fatality; it actually means they drive about 80 million miles for each fatality. (I think that here, Zipper simply took the wrong reciprocal.)

But even if we assume he got that right, there’s a second, subtler math error: For evaluating the safety of Waymos, he switched from the first strategy (vehicles miles traveled per death) to the second (vehicles’ travel per involvement with a fatal crash). But all vehicles will appear far more dangerous if you measure each car’s “miles traveled per involvement with a fatal crash,” rather than measuring the fleet’s “miles traveled per death” because most fatal crashes have multiple vehicles involved — and certainly all the fatal crashes that Waymo has been involved in had multiple vehicles.

What happens if you do an apples-to-apples comparison? My own calculation is that if you evaluate miles traveled per involvement with a fatal crash for humans, you get 56 million miles per fatal crash involvement for humans, so Waymos look slightly safer — though with so few data points, this is not a super useful analysis to run.

An alternative approach is to count a two-car crash with one death as 0.5 deaths on Waymo’s account. This is the approach favored by Phil Koopman, who has a long, interesting analysis of how our choices about measuring AV deaths create incentives for AV companies. He wrote of the fractional-deaths approach, “this is the only math that corresponds to the notion of fatalities/mile = total fleet fatalities divided by total fleet miles. Anything else ends up over-counting or under-counting harm. By this math, at this point Waymo has accrued just shy of 0.5 fatalities: 0.33 in a three-vehicle crash including a motorcycle, and 0.14 from a seven-car crash, totaling 0.47 fatalities.”

If you’re using this approach, you can directly compare Waymo’s deaths-per-miles-driven to the human deaths-per-miles-driven. Humans drive 80 million miles for each fatality; Waymos had, as of September, driven 127 million miles with 0.5 fatalities.

This is, to be clear, not enough data by itself to say that Waymos are safer than human drivers. We have enough data to say that Waymo is safer than human drivers, but it comes from the airbag-deployment and serious-injury data, not from these death statistics that are incredibly sensitive to any single incident.

A mathematically precise look at the fatality numbers at least suffices to show that Waymo, compared apples-to-apples with humans, does not appear more dangerous than human drivers. But deaths are simply so rare that this is hard to draw strong conclusions about.

Zipper summed up this section on the sparse fatalities data by saying, “To summarize: We don’t yet know whether a robotaxi trip is more or less likely to result in a crash than an equivalent one driven by a human.”

No! To answer whether a robotaxi trip is more or less likely to result in a crash we look at the crash data, for which there is a large and adequate sample and where it’s very clear that Waymos are less likely to result in a crash. An accurate summary would be that we don’t yet know whether a robotaxi trip is more or less likely to result in a fatality because fatalities are so incredibly rare.

But also, come on. If Waymos are far less likely to hit pedestrians — and they are — far less likely to have airbags deploy — and they are — and far less likely to get into crashes in which anyone is seriously injured, then we may not yet have data on fatalities, but we have more than enough grounds to place our bets about what that data is going to say. Policymakers routinely act on much weaker evidence than “this dramatically reduces serious car crashes.”

We don’t have perfect information, but we are not in a state of perfect ignorance either — and we’re frankly much closer to the perfect information state than the perfect ignorance state.4

There are other, reasonable concerns about AVs.

Zipper’s final point was that autonomous vehicles, even if they reduce road deaths, might not be the most cost-effective way to do so.

This too strikes me as wrong. Cost-effectiveness is a good question to pose about government spending initiatives, but taxpayers have to pay zero dollars for Waymo. The only policy change necessary to get autonomous vehicles in your community is to not ban them.

I’m in favor of protected bike lanes, bus stops, crosswalk improvements, speed cameras, and visibility improvements, but none of them are a reason not to allow autonomous vehicles.

There are, of course, reasons to worry about autonomous vehicles. I’ve written about how I sympathize with the fear that we’ll eventually ban human drivers, and I also obviously sympathize with worries about congestion and pollution.

But I don’t think there’s a lot of ambiguity in the safety data. And I worry that a lot of people are going to die if we indulge uncertainty that isn’t actually there.

Correction: A previous version of this article described a data set as showing 1.26 fatalities for every 100,000 miles driven instead of 1.26 deaths for every 100 million miles driven. The text has been updated.

More on autonomous vehicles:

Please let the robots have this one

Welcome back to The Argument’s monthly poll series, where we press Americans on the issues everyone’s fighting about. Last time it was free speech. This time it’s AI. Our full crosstabs are available for paying subscribers here and our…

Why women should be techno-optimists

Welcome back to The Argument’s monthly poll series, where we press Americans on the issues everyone’s fighting about. Last time it was free speech. This time it’s AI. Our full crosstabs are available for paying subscribers here and our methodology can be read

A disclosure: Waymo is a division of Alphabet, the umbrella company that owns Google, where my wife works.

Cruise, the GM-owned self-driving car company, ran over a pedestrian after they were hit by another car, then lied about it to regulators. Cruise’s self-driving program was effectively shut down over the incident.

You would like to think human drivers wouldn’t do this, but actually, they absolutely do.

What about if Waymo convinces people to take a robotaxi instead of the train, when robotaxis are more dangerous than trains? This is one of the points in the article that is perfectly valid, but I wish had been embedded in a different article. I think that the effects of Waymo and similar options on the use and economics of public transit is an important question, but I don’t think it makes sense to treat it as an unknown about Waymo safety. I’d love to see questions about whether Waymos will result in far more traffic on the roads, whether they will reduce use of public transit (or increase it by solving last-mile problems), and how they will reshape our cities. But I think these questions are not best embedded in an argument over Waymo’s safety record because there’s a lot more uncertainty about this stuff than about the safety questions.

I basically agree with this article but I will make two complaints.

1. We certainly have lots of data about crashes from Waymo, but there's lots of other data we don't have that's safety relevant. To start with, crashes are reported in detail but miles driven is just something you get from their advertising blog posts. We don't have breakdowns of highway vs city street, deadhead vs passenger, etc.

More significant for safely is that we don't know anything about disengagements and remote assistance. This doesn't impact how we should assess waymos safety record so far but is significant for how to assess it going forward.

2. I think footnote 3 is wrong because Waymo is a service not a car. If we were considering the safety record of a similar level AV that people owned I would agree that the impact on public transit is not the same as the safety record and belongs in a different conversation. But instead Waymo effectively is a public transit system. So you have to consider whether it's getting people out of Ubers significant safety win), their own car (big safety win but way more variance), or off of the bus (safety negative).

Thanks so much for writing this piece! May I gently suggest that Zipper deserves a little more holding-to-account than your admirably generous response? His opening sentence:

“If a chorus of wide-eyed boosters and enthralled journalists are to be believed, self-driving cars from companies like Waymo, Tesla, and Zoox can bring about road safety nirvana — if only US regulators would get out of their way.”

“wide-eyed” and “enthralled” are ad-hominem attacks on the legitimacy of those Zipper disagrees with. He shouldn’t do that even if he has evidence to support his description — but to my reading he doesn’t supply any. Next, his close:

“Let’s give AV companies yet another benefit of doubt and assume that their technology proves so powerful that it produces a net reduction in crash deaths even with an increase in total car use. Still, that is not enough to justify government leaders prioritizing AVs as a road safety solution. The reason is quite simple. Good policymaking entails choosing the most cost-effective ways to address a public problem, in this case traffic deaths. Self-driving technology is only one of many tactics available to reduce crashes, and it is not at all clear that it offers the highest return on investment. To offer just a few alternative approaches: Cars could be outfitted with Intelligent Speed Assist — a far simpler technology that automatically limits the driver’s ability to exceed posted limits. Regulators could restrict the size of oversized SUVs and pickups that endanger everyone else on the road. Cities could build streets with features that are proven to reduce crashes, such as protected bike lanes, wider sidewalks, roundabout intersections and narrower travel lanes. States could legalize the installation of automatic traffic cameras that deter illegal driving. Bus and rail service could be expanded. Unlike autonomous vehicles, these strategies have been reliably shown to reduce crashes — and without AVs’ mitigating risk of expanding total car use.” [new lines removed for space]

Zipper considers “expanding total car use” a “risk. He falsely presents *allowing Waymo to operate* as *prioritizing AVs as a road safety solution*. He lists his preferred policy changes as options that “regulators” / “cities” / “states” all “could” do without acknowledging the obvious first obstacle that *voters don’t want them to implement those policies*. As Zipper is surely aware, normal people like buying giant SUVs that can go 100mph, and many jurisdictions have removed automatic traffic cameras at the behest of angry voters (BTW, this fight seems worth having). I mean, dude: putting in roundabouts just doesn’t conflict with letting Waymo serve its customers. The biggest conflict is in the last sentence: voters will overwhelmingly reject the proposition that because car trips can produce accidents, public policy should restrict voters’ access to car trips.

Zipper’s piece is rife with evidence of bad faith. I think the burden is on him to reply with reasons why we should treat his essay with respect rather than dismissal.