Jon Stewart has become his own worst nightmare

Econ 101? In this economy?

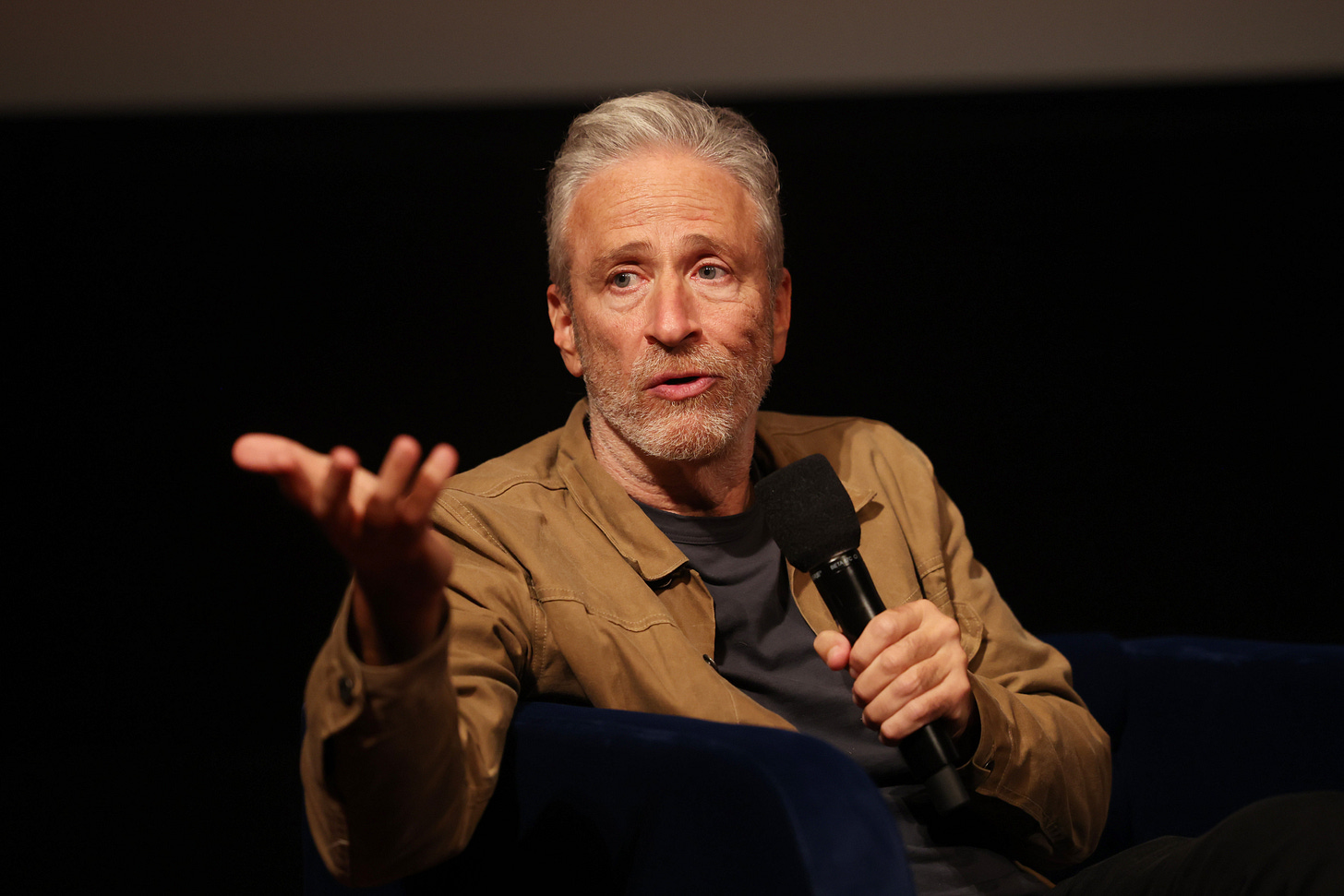

Last week, comedian and political commentator Jon Stewart published an interview with Nobel Prize-winning economist Richard Thaler where he revealed that despite his nearly 30 years as a prominent commentator on American politics and policy, he has no idea what economics actually is.

Stewart ostensibly brought Thaler on his show to explain what the field of behavioral economics is. But as Stewart’s misrepresentations and misunderstandings piled up, Thaler quickly found himself in the position of defending and explaining basic economics, the kinds of things many of us learned in introductory college classes.

In one of the more egregious examples, Thaler began explaining how behavioral economics might influence laws or regulations to address climate change by pointing out that most economists, in accordance with standard economic theory, believe that the optimal response to excess carbon dioxide emissions is a carbon tax.

Before his guest could get any further, Stewart laughed disbelievingly and argued “May I suggest that that’s incorrect?” adding that “The minute you put a carbon tax on, people see their energy prices go up, and you will no longer be serving in office politically.”

This was a bizarre non sequitur, because while it’s true that a carbon tax would be politically dicey, Stewart’s concern about political risk is totally unresponsive to the question of whether it’s an economically optimal policy solution.

Thaler tried to explain why economists like a carbon tax, but the moment he said that it helps people behave in a socially optimal way, Stewart interjected again, rejecting the premise: “But that’s not economics, economics doesn’t take into account what’s best for society!” he exclaimed, adding that “The goal of economics in a capitalist system is to make the most amount of money for your shareholders. So my point is, since when is economics about improving the human condition and not just making money for the companies that are extracting the fossil fuels from the earth?”

At this point it became clear that Stewart has conflated the entire field of economics with a half-remembered, left-wing caricature of capitalism. a left-wing caricature of capitalism.

Not everyone knows, or needs to know, what economists do. But if you’ve spent the bulk of your life arguing about economic policy — interviewing experts and leading politicians and thinkers — I think it’s pretty shocking to reveal that you’ve never had any idea what you were talking about.

Throughout the interview, Stewart seemed to believe that economics is just a sophisticated justification for letting rich people and corporations do whatever they want. And this total lack of basic understanding renders him an inept translator of politics and an ineffective force for the very policies he says he supports.

Jon Stewart? The neoclassical economist?

Economics is a social science that seeks to understand how people, firms, and governments allocate resources. Microeconomics studies individual or firm behavior, while macroeconomics studies aggregate phenomena like inflation, unemployment, and economic growth.

Here are a few ways that economic models have helped make the world a better place:

The time between recessions has gotten longer as economists have gotten better at monetary policy.

The development of randomized controlled trials helped us learn to improve interventions in the developing world, leading to more than 5 million Indian children getting access to tutoring and expanding access to vaccines and other preventative health care.

Economist Alvin Roth redesigned the matching system for kidney donations to find chains of compatible swaps. Thousands of life-saving transplants now happen that otherwise wouldn’t.

These are some of the field’s greatest accomplishments, but even when you look at what economists are working on day-to-day, it’s hard to reconcile with Stewart’s depiction. For example, this morning, in the National Bureau of Economic Research’s weekly roundup of new working papers, there is a paper about how taxation may have influenced the French Revolution, a paper on how protests in Nigeria could have shifted the spatial allocation of redistribution, a paper on how immigration improves mortality among elderly Americans by increasing the size of the care workforce and exactly zero papers interested in the question of increasing shareholder value.

Which brings us to the most cringeworthy moment of the episode, when Stewart outlined his optimal climate change policy scheme. He rejected the idea of harsh mandates where the government tells you “you are not allowed to use this much electricity or you are not allowed to use this much gas.”

Instead, he said he wants a policy regime that recognizes that people are going to use products that make their lives easier: “People want the convenience that modern life has provided them, whether they live in the Global South or whether they live in our [country].”

To solve this problem, he argued, government needs to mitigate climate change through carbon capture technology and create “robust markets in damage mitigation and carbon mitigation.”

Thaler only let a small smile slip as he responded to this policy agenda by pointing out that Stewart’s position is identical to the one he had just mocked.

A carbon tax, or the standard economic prescription for responding to climate change, is the exact thing you would propose if you a) didn’t want the government telling everyone what to do, b) believed people were fundamentally committed to buying the cheapest, most efficient thing, and c) wanted to create the incentive for carbon mitigation markets.

Stewart arrived, in the abstract, at the standard economic answer, but because he has seemingly failed to learn any actual economics over the last 30 years, he appeared incapable of understanding what his stated views actually imply.

In his defense (sort of), I do think that Pigouvian taxes are not well understood by most people (though again, most people do not make their living talking about politics and policy). So I think it’s worth spending a moment explaining why these taxes are such an elegant solution to problems like climate change.

As Stewart explained, carbon, unlike many other bad things, is actually a very good thing with very bad side effects. Energy makes everyone’s life better, and a more prosperous, fair, and just world would come with dramatically more energy use as the Global South and lower-income people get access to stable and abundant energy.

The problem, of course, is that we get most of our energy from carbon-emitting sources that carry with them tons of negative costs, like increased mortality from heat waves, air quality degradation, sea level rise, and property destruction from extreme weather events, to name a few.

The fundamental problem is that people who are using energy are not actually paying those costs. They’re just paying what the utility charges them to turn on their lights, which is significantly less than the costs all of society bears when more carbon is pumped into the atmosphere. The solution, then, is to try to make the people who are using the energy actually pay for it.

Pricing carbon accurately is pretty complicated, though. Figuring out the costs of all the negative side effects of carbon emissions isn’t straightforward, and economists have … spirited arguments about how high the price on carbon should be. The Biden administration, when debating what the social cost of carbon should be in doing benefit-cost analysis of its various regulations, set it at around $190 per ton (some economists think it should be more than $200).

The Trump administration has pushed it to below $10.

These were incredibly live debates, particularly during the Biden years, but Stewart doesn’t seem to have paid any attention to them or have anything interesting to say about them at all.

The paranoid style comes for Economics

My frustration is not only with Stewart. He is merely a recent and high-profile example of a broader phenomenon: the rise of economics denialism across the political spectrum. Whether it’s the ascendant postliberal right or the Biden administration, economists have, to the nation’s detriment, lost cachet.

Economists’ dwindling stature is largely about the Great Recession. Economists helped design a policy response which was perceived at rescuing banks at the expense of the everyman. Whether or not this criticism is fair, the aftermath of the financial crisis was devastating for the profession.

None of this is about rescuing economists from their ivory towers and lucrative private sector jobs, it’s about how policy gets worse when politicians and political commentators ignore the field best suited to help us think through tradeoffs and model the complex systems governments tinker with and build every day.

As economists have been exiled from the Republican Party, it’s become normal to claim that tariffs won’t raise prices (they do) and will save manufacturing (they don’t). The president casually suggested — against evidence — that institutional investors are the reason young people can’t buy a house, a claim mirrored by his opponents on the left. And, of course, the left’s increasing fixation with bringing draconian price controls back reveals how little proponents are thinking through the damaging consequences.

In public policy debates, economists are usually the voice raising the existence of trade-offs. Yes, you can let the big banks fail but the cost of that could have been a second Great Depression. Yes, you can set up an incredibly harsh criminal justice system, but the fiscal cost will be extraordinary and you won’t actually be effectively deterring crime. And yes, you can forgive student loans, but you’re transferring wealth to a relatively affluent group.

Jon Stewart? The comedian?

Stewart’s most famous TV moment was in 2004 when he went on CNN’s Crossfire — a nightly show that pitted a liberal and conservative pundit against one another.

At the time, Stewart was the popular host of The Daily Show on Comedy Central. But he came on the show with a mission to confront the hosts — that day Tucker Carlson and Paul Begala, former advisor to President Bill Clinton — over what he felt were their journalistic failures.

“I made a special effort to come on this show today because I have … mentioned this show as being bad,” Stewart told Carlson and Begala, adding, “It’s not so much that it’s bad but that it’s hurting America.”

Over the course of several minutes, the shape of Stewart’s critique took shape: Crossfire is kayfabe, theater, a un-self-aware performance of partisan hackery that helps “politicians and the corporations” while hurting the rest of us.

Stewart was funny and charismatic, and his willingness to lodge this criticism so forcefully all contributed to this clip going viral — particularly enjoyable was when he called Carlson a dick. A few months later, Crossfire was canceled, and Carlson was out at CNN. Up in the air was how much Stewart contributed to this, but CNN’s then-president explained that he wanted the platform to move away from debate shows and cited Stewart’s criticism.

Carlson, Begala, and Stewart spent a lot of time talking over one another, so there was no real opportunity to fully air the comedian’s exact grievances. But in a retrospective published by Begala a decade later, the author recounted a much longer conversation he had with Stewart off-stage.1

In it, Stewart expanded on his argument, adding that he thought it was absurd to force every issue into a simple binary story between right and left. He said that choosing guests who represented the extremes was erasing the variety of more nuanced opinions that most people actually held.

I haven’t actually watched much Crossfire outside of this one clip2, so I can’t really comment on the veracity of his criticism, but re-watching it in 2026, Stewart’s biting critique could just as easily describe his older self. The man who was once frustrated at media that oversimplified conflict and forced it into a left vs right binary now sees all economic policy questions as a morality play between good guys and bad guys.

At the time, Carlson tried to point out that Stewart was a hack himself, having interviewed Democratic presidential nominee John Kerry and only lobbing softballs his way. Stewart effectively neutralized that argument by pointing out that CNN and Comedy Central were different outfits with different responsibilities.

But 20 years later, that argument doesn’t hold water. Stewart’s platform is so large that a confusing interview with an economist got more than 200,000 views in four days. His YouTube channel has more than 700,000 subscribers, and he has basically a full-time politics show featuring governors, the former vice president, and top journalists and media voices who all jump at the chance to reach his audience.

All that power and yet a complete lack of curiosity and serious engagement with why well-meaning people might disagree with him? Well, I suppose I just don’t find that very funny.

I’m a regular listener to the Jon Stewart podcast you’re right he does bring on professionals and influential politicians as well as subject matter experts. The number of times that he will say in an interview oh that is so interesting and try to learn from his guest is countless.

I would agree the podcast last week was not great, but I think at least part of that had to do with the guest the “expert” was almost impossible to understand between his speech, cadence and the way he was stepping around ideas and not modifying them to meet his audience. If you go on the Jon Stewart podcast you’re not trying to reach people who have taken advanced economics. Also, as someone who took Econ 101 and really didn’t understand it. I was looking forward to actually learning something, and I came away from that interview, extremely disappointed and more confused than when I started just like Jon Stewart.

I would agree with one of the previous comments is interesting that you write this article the day you release a Ross Douthat interview. Who changes his mind all the time.

This piece is kind of strange in that it is ostensibly a rebuttal of left wing critiques of economics, but it engages in what's core to that critique - there is no such thing as "economics." Ask economic questions are subject to internal scrutiny and controversy, as is true in any site of human academic or intellectual endeavor. For a very long time, conservatives and free marketers have tried to suggest that all economic questions are settled and that "economics says X," but economics doesn't say anything; it makes no more sense than saying "politics says x." It's all contested. And while this has been a left-left critique of the use of economics in political argument, it's also become a pretty standard issue progressive one too. Paul Krugman made great hay out of the abuses of "economics 101 says," in his arguments about freshwater vs saltwater economic schools, for example.

The classic case of misapplied "economics 101 says" is the minimum wage. For years, free market types insisted that $15/hour minimum wages would cause mass unemployment - "it's Econ 101!" But now we have a mountain of empirical data showing that that hasn't happened and the $15/hour is a banal fact of life in many places. Of course some people still insist that it kills jobs, but that's the whole point, right - "economics" never says anything. It's all debatable, and saying "it's Econ 101" is just a way to suggest objective unanimity where there is none.