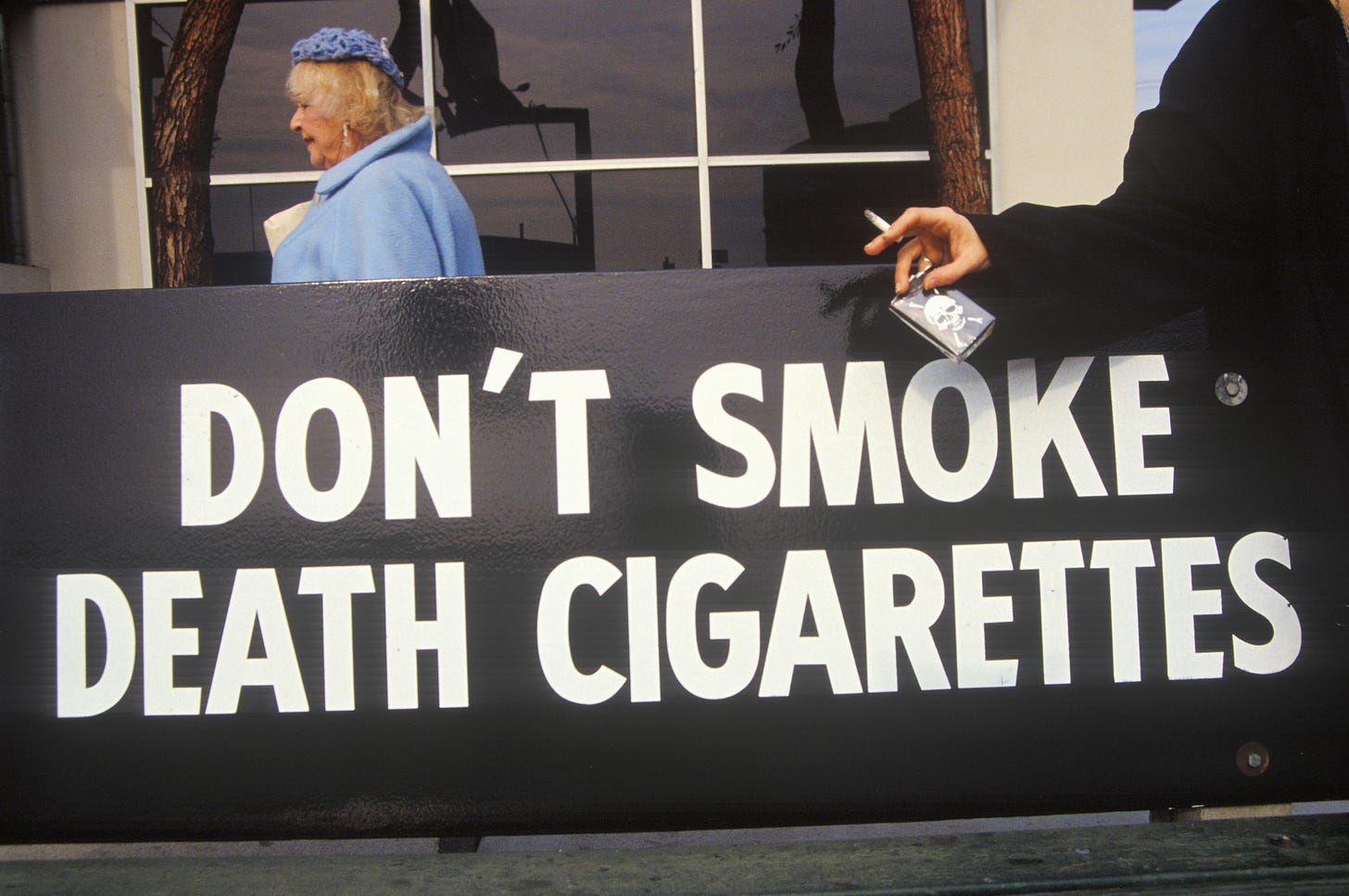

Treat Big Tech like Big Tobacco

The problem with TikTok and Facebook isn't their size

The problem with Big Tobacco was not that it could charge excess prices because of its market power. The problem with Big Tobacco was that cigarettes were too cheap. Cigarettes caused both externalities to society and also internalities between the higher-level self that wanted to quit smoking and the primary self that could not quit an addictive substance. So, we taxed and regulated their use.

The fight regarding social media platforms has centered around antitrust and the sheer size of Big Tech companies. But these platforms are not so much a problem because they are big; they are big because they are a problem. Policy solutions need to actually address the main problem with the brain-cooking internet.

It is true that these are very large, economically dominant companies, and their extremely rich founders have degraded our politics. But the pre-Khan antitrust framework is about whether these companies can persistently exert pricing power and there are real questions about whether that is true.

Google was supposedly the only force in search, but now ChatGPT poses a real threat to Google’s search business. Meta had its dominance in social media upended by TikTok, and social media writ large — the version where people view content created and shared by their friends on an app — is dying off in favor of recommended short-form video on Reels, TikTok, and YouTube, all of which are competing for attention. Sora, an OpenAI video-generation platform, could disrupt these firms. Competition is rampant.

The problem is what all these companies are competing to do. The data we have, let alone the data I expect we’ll eventually have, indicates that the modern internet is addictive, makes us miserable, and perhaps makes us hate each other.

One study showed large externalities to nonusers of TikTok and Instagram, leading many people to use the sites for FOMO reasons when they would prefer not to. Others show people are happier when they’re paid to stay away from social media. At a societal level, across the world, we’ve seen preliminary evidence of the damage from addictive social media, but ecological studies are difficult.

For three decades, internet providers were merely passive hosts of third-party content, immune from liability faced by publishers. That grant of immunity was foundational, and the costs of such freedom were wildly outweighed by the benefits of the internet.

Both of these facts are no longer true. Social media companies are no longer passive hosts but active curators. And the costs of these products are now too high to ignore. They make us addicted to their apps with slot machine-style precision, and they are now helping creators fake reality with text-to-video generation.

The answer is not to destroy these companies or pull the government into the messy and probably unconstitutional world of directly regulating speech. The answer is to remove the special protections they have been granted and finally allow people harmed by these products to hold these companies liable.

Holding social media companies accountable

Chris Hayes’ book The Sirens’ Call makes the case that attracting our attention is the objective function of social media algorithms. It further posits that we are unable to exercise our second-order desire to ignore them, just as many people wish they could resist the urge to smoke or eat junk food.

Indeed, Jerusalem Demsas’ recent article arguing for culture-first solutions acknowledged that very problem: the distinction between the higher-level self that would like to reduce social media consumption and the basal self that would like to infinitely scroll. These are precisely the sorts of problems where regulation and societal commitment devices can help to achieve a better equilibrium.

As Matt Lackey, founder and CEO of Tavern Research, persuasively argued, we have learned over the course of computing history that reinforcement learning with a clean reward signal allows computers to beat humans in a wide range of domains. When computers are given a game with an objective function and enough computing power, they master the game.

Backgammon, chess, go, Jeopardy!, and poker are games with clean reward signals that have been solved by computers. Computing power is still increasing exponentially and the complexity computers will be able to solve for only increases.

The problem is that human attention can also be gamified — how long do you stay, how much do you click — and it will also be something that they will ultimately master. The Netflix algorithm employs reinforcement learning in much the same way that chess was taught, except now time spent in-app is the reward.

So far, Big Tech has been trying to master our attention with content created by other humans. But soon, we may be contending with AI-generated content created by the very same platforms that know what we pay attention to the most. Meta has already indicated the 1.0 version of its “Vibes” concept is coming. Regulators need to get ahead of this.

The law that built the internet no longer fits it

Recommendation algorithms have allowed large platforms to turn our attention into a solved game. I say this with a lot of trepidation at a time when free speech is seriously threatened, particularly after seeing the harms that the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act wreaked on sex workers. But the time has come to amend Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (CDA 230). Specifically, lawmakers should remove protections for platforms that actively promote content using reinforcement learning-based recommendation algorithms.

CDA 230 is the law that gave immunity to platforms for speech from users, and it has been the backbone of the modern internet. If somebody posted defamatory content about Jerusalem on Substack, then Substack is not liable to Jerusalem for it.

Without this law, the internet as we know it could never have existed. If every website was liable for anything individuals posted, that would eliminate all comments sections, blogs, social media sites, and photo and video platforms. But the internet used to describe something on balance good — now it describes something on balance awful.

The internet is awful not because there is too little speech but because the large companies at its center push horrible, addictive, user-generated content on us with no legal responsibility whatsoever. They are not passive providers, and, in fact, they are now creating video content based on text prompts. Users are not organically coming across enraging, polarizing, and addictive content. It is being served up to us on a silver platter.

Message boards, group chats, classified ads, reverse-chronological feeds of any site, and Wikipedia would not be touched by an amendment of CDA 230 for recommendation algorithms. Good old-fashioned upvoting and downvoting could be given a safe harbor.

Perhaps these companies would, like tobacco companies, keep creating their products and simply litigate all of the complaints that come their way regarding the health problems they created. Some members of Congress have at least started to think through this issue.

The Supreme Court might (even correctly) say that regulating a recommendation algorithm directly — rather than removing congressionally granted legal protections — regulates speech acts in a manner that violates the First Amendment. The government, for example, making it illegal for a recommendation algorithm to promote “medical misinformation” would not be content-neutral and would wade too deeply into regulating the specific content of speech.

But if a company is using reinforcement learning to maximize the amount of time users spend in the app and promoting content into a feed to try to keep eyeballs there — be it YouTube, TikTok, Instagram Reels, or Twitter — then the company should no longer be treated as a passive host that receives the protections of CDA 230.

Some cases have already considered whether algorithmic recommendations fall under the existing protections of CDA 230. In the 2019 case Force v. Facebook, Inc. a family alleged that Facebook helped Hamas promote terrorism by hosting their content and actively promoting it through their algorithm. The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals (the federal appeals court covering New York, Vermont, and Connecticut) held that Meta’s algorithm for recommending content qualified for CDA 230 protections as its recommendation algorithm was “neutral.”1 The 9th Circuit ruled similarly in Dyroff v. Ultimate Software Group in 2019.

But the 3rd Circuit, which covers cases in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and the Virgin Islands, held in 2023 in Anderson v. TikTok Inc. that the family of a 10-year-old girl could sue TikTok for recommending dangerous content that led her to fatally attempt the “Blackout Challenge” — a dangerous choking “game.” The court ruled that TikTok was not passively hosting content but actively recommending dangerous content to users, writing that they “engage in protected first-party speech under the First Amendment when they curate compilations of others’ content via their expressive algorithms . . . [and so] it follows that doing so amounts to first-party speech under § 230, too.”

The protections of the First Amendment are vital for a functioning democracy and great care should be taken in thinking through these amendments. Obviously, all speech on the platforms should and would be protected in the same way all speech is protected: Defamation claims require actual malice, accusations do not warrant prior restraint, and anti-SLAPP laws are taken into account.

But amending Section 230 to follow the standard set by the 3rd Circuit nationally would be sensible and would not endanger passive providers. Companies that host content fed in reverse-chronological order or show you content from a self-selected social graph could be given a safe harbor and continue to receive the protections of CDA 230. Or perhaps companies whose recommendation algorithms were merely not black boxes, as reinforcement learning algorithms are, could suffice.

These are delicate questions, and I would almost always err on the side of free speech. But recommendation algorithms are not themselves acts of speech, particularly where they are such black boxes that it is unclear if companies could even tell us about their neutrality or the reasons for the recommendations themselves.

And even were they considered speech, First Amendment protections are not limitless; coercive threats and threatening verbal harassment are illegal, and regulating advertisements for cigarettes is permissible. These algorithms are vectors for social destabilization, and their advocates show little interest in regulating themselves.

AI advocates want no regulation and no way for Americans to make them internalize the externalities of their product

Last week, after The Argument published Kelsey Piper’s piece arguing that we should be able to sue AI companies for the harms they cause, AI boosters like Patrick McKenzie were up in arms. They argued that doing so would lard costs onto AI products and that lawyers and doctors were attempting to protect their cartel.

Taking their arguments seriously is somewhat hard in light of the fact they are spending a trillion dollars to try to build a digital god. But as an on-the-record “AI is useful” plaintiff’s attorney, I think I have some insight here.

When a product imposes externalities — harms not borne by the producer — we can typically address that in a few ways: We could ignore the costs completely, which is what these advocates seem to want, like manufacturers wanting to pollute the water without cost. We can try to regulate away the externalities, which AI advocates (probably rightly) say will slow growth in the technology and let countries without such regulations win the race, which would be bad. We can try to tax those externalities, which in this case would be extremely hard in many ways.

Or, as we often do in America, we can let the legal system impose costs relating to the harms created by the product makers as a post hoc regulation. This will allow innovation and growth without intrusion by the government on the front end.

Remember, many of these advocates are people who put p(doom) — the odds that AI will be so powerful that it will destroy humanity — at some number greater than zero and are still building it anyway. At minimum, we should think about how to impose the right amount of cost and friction onto the product.

Litigation is the lowest-cost regulator for AI, and forcing companies to internalize the costs of their product,2 in order to exercise due care, is a small cost in the grand scheme of nearly $1 trillion in capital expenditures.3

When Waymo vehicles get in an accident due to their failures, Alphabet should be responsible.4 When an LLM explains in detail to teenagers how to harm themselves, the LLM developer should be responsible. If your text-to-video content creator leads to somebody getting arrested or hurt, you should be responsible.

And yes, if a black-box content algorithm causes depression or promotes harmful behavior among children, and the creators know the algorithms will do this and then make them as addictive as possible without any detailed knowledge of their inner workings except that they grab and hold our attention, they have not exercised due care and should be subject to suit.

NYU Law professor Catherine Sharkey argued that products liability, with a feedback loop between tort liability and regulation, is the right way to regulate AI products because the technology is so novel. Tort liability, she argued, allows us to be flexible in regulating AI products at a time of regulatory uncertainty.

Tort liability assigns the duty to protect to the “cheapest cost avoider,” which in the case of AI will be the creators of the platforms. As Sharkey argued, instead of trying to cleanly attribute the harm of AI to each party involved in its creation, courts should simply assign liability to the party that can most easily limit harm at the lowest cost. Over time, regulations can evolve out of these harms.

The harms and benefits of black-box content recommendation algorithms, LLMs, and Waymos are all quite distinct. But that variety speaks to the benefit of using tort liability to regulate their harms.

And in the world of product liability, their bigness may in fact be a benefit, not a harm. With tort liability, if a firm has no money, it is essentially free from the harms it causes; it is judgment-proof.

Individual taxis are incorporated individually and often have very low insurance coverage, meaning people horribly injured in an accident cannot recover enough money to pay for their treatments in full. But Alphabet and Waymo have billions of dollars.

When Wan 2.2 or an open-source model puts video out into the world, the people harmed by the video might have no recourse, and our politics might not have recourse either. But with OpenAI and Meta, we do not have that same problem.

The regulatory and tort solutions I am putting forward in this article may not ultimately be precisely correct — I’m more than open to that possibility. But our current regulatory regime is failing us, letting large companies harm us with impunity, and we must figure out how to make them internalize their harms.

A dissent from the late Judge Robert Katzmann argued that recommendation algorithms cannot be considered mere publishing.

For example, require reinforcement learning with human feedback to reduce the chances that these LLMs will harm society.

We have legal tools domestically to address some of the harms. The Take It Down Act provides for civil and criminal remedies for failure to take down pornographic deep fakes. There are state laws that make unauthorized use of likenesses illegal, but only about half of states have such a law protecting the right of publicity. Obviously there are copyright protections.

While perhaps beyond the scope of this article, in the specific case of self-driving vehicles, a legal regime of strict liability might make the most sense. There, the self-driving car companies might be held liable for any defect in their product that caused an accident, whether or not they exercised due care in trying to prevent the outcome. If Waymos are as safe as I suspect they are, the ability to extremely cheaply insure against harm may be a competitive benefit to them.

TBF, screw this obsession with 230. Just tax them!

Curators are collage artists. Their medium isn't paint, or stone, or any other raw material, but the finished work of other artists. When a content curator offers a collection of media, the collection itself is the aesthetic creation of that curator. They're like fashion stylists who create collections of garments and accessories which form distinct identities, beyond the characteristics of any of their components.

Algorithms are nothing more than automated curators, and the feeds they generate are nothing if not original, characteristic content, authored by software — software which, itself, was ultimately coded by human beings, on behalf of a media company, and published for use by that company.

So why should producers of this sort of *original content* — that is, the algorithm-generated content feeds — be immune from liability for harm caused by their consumption?

This is really a very important question!

What if their Communications Decency Act, Section 230 (CDA 230) protections really were removed? Would platforms be compelled to offer only content produced by others, algorithm-free, in an environment which would continue to shield them from liability? Would it be so bad if algorithmic feeds were replaced by directories which users would need to consult manually to find what they were looking for?

A solution like this would return the role of curation to users who would not only continue to be free to consume what they like but also, additionally, to *choose* the media they want to see, based on their own criteria and not the goals of content providers like Facebook or YouTube, who want only to harvest maximum audience attention — or else, insidiously, to direct audiences toward persuasive media, for the purpose of influencing them…